Fear, stress, relief: How CNA's Nivell Rayda tested positive for COVID-19 as cases spike across Indonesia

How is the situation on the ground in Jakarta, where COVID-19 cases have been rising steeply? CNA's correspondent Nivell Rayda writes about his experience.

Medical workers carry a woman on stretcher from an emergency tent erected to accommodate a surge of COVID-19 patients at a hospital in Bekasi, West Java, Indonesia, Monday, June 28, 2021. (AP Photo/Achmad Ibrahim)

JAKARTA: It was like my heart leapt out of my chest and dropped to the floor.

“Madam, you have tested positive (for COVID-19),” a doctor in full personal protective equipment told my wife as she lay on the examination table. My wife was too unwell to respond or display any emotion.

She had been feverish for the last two days. She also had bad body ache and a sore throat. Her lips were so dry that they were peeling.

She actually felt better that morning, only to worsen as the day progressed. I had suspected that she had contracted dengue fever or typhoid.

We have been adhering closely to the health protocols – at least we think we had – so we did not suspect that we might have contracted the coronavirus.

“Should I be tested as well?” I asked the doctor.

“Of course,” she replied.

The realisation that my wife and potentially I had COVID-19 numbed my senses. I almost did not feel a thing when the doctor took samples from the back of my nose.

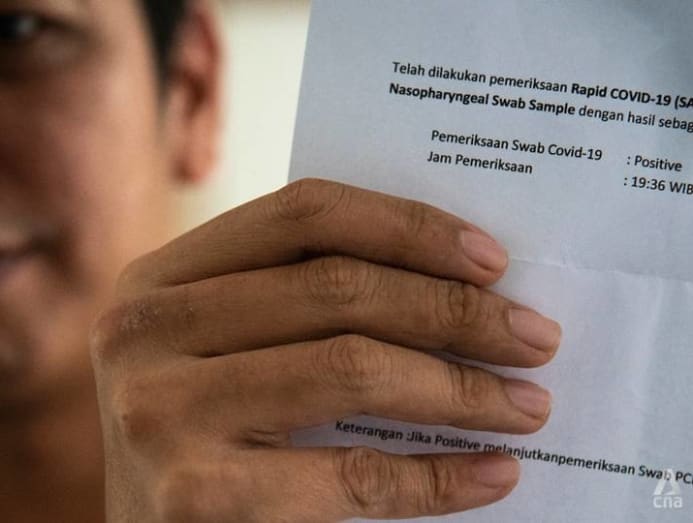

I watched anxiously as the chemicals inside the rapid antigen test cartridge reacted to the recently taken samples. Within minutes, two red lines were visible, confirming what the doctor had suspected. I had also tested positive for COVID-19.

As the doctor prescribed some medicines and supplements for us, many thoughts raced inside my head.

“This is the worst possible time to have COVID-19,” I thought to myself. Across Indonesia, the number of new daily cases were rising steadily after people were believed to have ignored Idul Fitri travel curbs and reports of the Delta variant being detected in Indonesia.

READ: Aerial images of expanding graves capture Indonesia's deadliest days

On Jun 24 when we both tested positive, Indonesia recorded 20,574 confirmed cases within a 24-hour period, around double the daily infection rate the week before. This week, the daily caseload surged above 35,000.

The number of cases grew so drastically that across Jakarta, where I live, hospitals were struggling to cope with the influx of patients.

Three days before we tested positive, the Jakarta health agency announced that the city’s 9,000 COVID-19 isolation beds were 90 per cent occupied. It advised patients with mild symptoms to self-isolate instead of checking themselves in to hospitals.

As a result, small clinics like the one where we took our tests were filled with patients who had COVID-19 symptoms.

Dozens of people were queueing to get tested and judging from the expressions of disbelief after they emerged from the testing booth, it would appear that they too had tested positive.

The doctor said our symptoms were considered mild, despite the high fever my wife was experiencing. We were told to self-isolate. If we had difficulties breathing, the physician said that we would be referred to the hospital.

After we got home, I began to experience symptoms. I felt light-headed and warm.

I had trouble sleeping, not because of what the virus was doing to my body but to my mind.

“What if our condition deteriorate?” I thought. “Will I be able to find the help and care that we need?”

PEOPLE I KNOW WERE GETTING INFECTED

Although I did not feel as severely ill as compared to my wife, I was feverish and coughing frequently for the next few days.

After four days, I realised that I had lost my sense of smell. I had trouble determining if the food had gone bad.

Being generally fitter than my better half, I took on the responsibility of doing the household chores, which my wife later said I was not very good at.

I also prepared food and hot water for my bedridden spouse, who was asleep most of the time.

The reason why my symptoms were milder than hers could be due to the fact that I had been fully vaccinated. As a journalist, I was given priority in the national vaccination programme. I received Sinovac, which forms the bulk of the vaccines in the mass inoculation effort.

Indonesia had just begun rolling out vaccines for non-priority groups weeks before we contracted COVID-19. My wife, who has allergy issues, was not cleared by her allergy doctor to be inoculated.

Aside from my loss of smell, I was virtually symptom free by day five. My wife, on the other hand, was not improving despite visiting two different clinics for second and third consultations.

Meanwhile, the overall pandemic situation was worsening.

After we were diagnosed, the caseload increased steadily. I watched how the nation went from having 20,574 daily cases on Jun 24 to 38,391 on Jul 8.

In the span of two weeks, more than 300,000 people had been infected while more than 7,000 people had died.

READ: Indonesians ignore warnings in rush to buy anti-parasite drug for COVID-19

Among those who had tested positive for COVID-19 were my personal friends and families. In my neighbourhood alone, 12 people contracted the coronavirus including one who had difficulty breathing and had to be rushed to the hospital.

I tried to stay positive. But everyday, I would read news of how hospitals were so full that health workers had to treat patients inside tents erected at the hospital’s carparks.

From my home, I could hear the blaring sounds of ambulances passing through every other hour along a major street less than a kilometre away. A nearby mosque announced the death of different local residents almost every night.

Meanwhile, cemeteries – even newly established ones – were reportedly running out of space.

HOSPITAL BED SCARCITY

When I checked social media, I would immediately be drawn to accounts of how people had either contracted the coronavirus or lost one of their loved ones to COVID-19.

“My mother-in-law passed away because we could not find a hospital willing to treat her,” said one friend on his Facebook page. “We had reached out to 15 different hospitals.”

Another friend told me that his mother, whose oxygen saturation level was way below normal and had difficulty breathing, had to be treated for four days at the emergency room because the hospital’s intensive care unit was full. She never received the medical attention that she needed and finally succumbed to her illness.

My social media feed also had many posts of people seeking information on hospital bed availability and where to obtain oxygen tanks.

Eventually, it was my time to seek information about hospital availability.

On day eight, my wife had developed another symptom: Severe nausea. She would not eat anything but two spoons of oatmeal and a few drops of honey that day. She refused to take any medication because it made her vomit.

She was convinced that she would not get better unless she was hospitalised.

That night, I began browsing the internet for hospital bed availability. I tried calling five different hospitals but no one answered. I also tried reaching out to every doctor friend I knew to see if the hospitals they are working for had any bed vacancies.

“Even health workers are struggling to find beds for their families,” one doctor friend told me.

READ: Indonesia turns to telemedicine for COVID-19 as hospitals struggle

I also tried to find doctors who would do house visits for COVID-19 patients so my wife would have her medication and nutrition supplied through intravenous therapy. The house visit doctors were so busy that they could only visit three days later.

A friend learnt that there were still several beds available at a hospital around 20km away from my house. However, the beds were in such high demand that the only way to get one was to go to the hospital so doctors there can determine whether my wife would need to be warded.

We decided to try our luck the following morning.

When we got to the hospital, there was already a long line of COVID-19 patients waiting to be examined. I left my wife in the car while I joined the queue. She was not alone. At the car park, there were many more sick people who waited in their respective cars.

There were about 20 people ahead of me. A nurse told me that I might need to queue up for three to four hours.

Inside the car, my wife was getting restless. It was searing hot and she was perspiring. Turning on the air conditioner would make her shiver. After an hour, she threw up again. “Let’s just go home,” she told me.

I am still not sure what happened. But she got better that evening and her condition has been improving steadily.

BETTER BUT NOT THE SAME

While writing this, I can say that the worst days are behind us. I have since tested negative for COVID-19 and my wife, who is still experiencing some very mild symptoms, appears to be on the mend.

We felt lucky that neither of us had pre-existing medical conditions. Our symptoms were considered mild and not life threatening.

We were also fortunate that we live in an era where food, medicines and groceries are just a few clicks away.

My wife and I are forever grateful to have friends and neighbours who would regularly send food, supplements and herbal medicines. We even had friends who volunteered to help if we needed to buy things that we could not order online.

We may now feel better but the body somehow feels different. I am more easily fatigued. My breath feels a bit laboured and I find myself struggling to say long sentences or hit the high notes when I sing and play the guitar.

READ: Indonesia ramps up oxygen output after dozens die amid scarcity

Perhaps these will go away. But I have to be prepared for the possibility that we might be experiencing the so-called “long COVID syndrome”, where some symptoms might linger for weeks or months after the infection is gone.

COVID-19 has also changed us mentally. We feel like we have to be even more careful. No more dining out. Never answer the door without a mask on. Always wear two masks when venturing out of the house and carry hand sanitisers and disinfectant sprays around.

I cannot afford to have my wife or myself infected for the second time, because who is to say that we will be as lucky again.

BOOKMARK THIS: Our comprehensive coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic and its developments

Download our app or subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest updates on the coronavirus outbreak: https://cna.asia/telegram