In a first, 5 inmates jailed multiple times tell all from inside Changi’s maximum-security prison

These recalcitrant offenders reveal their identities in CNA’s groundbreaking documentary, Inside Maximum Security. It is an unvarnished look at their lives of crime, their stint in jail as it unfolds and their battle to reform.

Inmates Boon Keng (left) and Graceson taking a breather before resuming their exercise routine during the two hours they have twice-weekly in their recreation yard.

SINGAPORE: He remembers the last time he saw his daughter. It was two years ago.

She was holding him and asked a question that is seared into his memory: “Can you just don’t commit any more crimes?”

But it was too late. Her father, Boon Keng, had already broken the law, again. A few days later, he was caught.

The 34-year-old is now in jail for the fourth time, serving a three-and-a-half-year sentence for theft, drug consumption, criminal breach of trust and breach of personal protection order. This time, his daughter, who is of school-going age, has not visited.

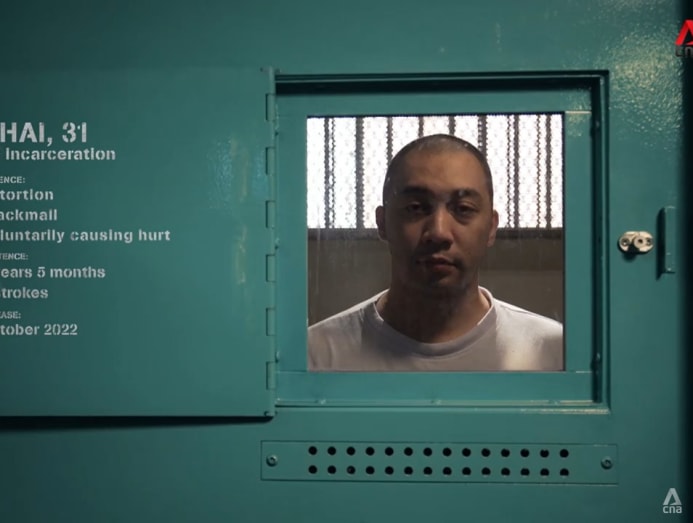

Khai, another inmate at Changi Prison, has not had a visit from anyone at all. While his 12-year-old daughter writes to him, he has not been in contact with his mother.

“After my late father passed (away), my stepbrother took my mum away,” said the 31-year-old. “On the day of my sentence, I couldn’t even see my mum. I couldn’t even talk to my mum.”

His father died of colon cancer in December 2020. Three months later, Khai started serving his 29-month sentence — with two strokes of the cane — for extortion, blackmail and voluntarily causing hurt. It is his sixth imprisonment.

This time, he reached the point where he told a prison officer that he felt like ending it all.

The two inmates are among Singapore’s most hardened criminals, who are incarcerated in Changi Prison’s maximum-security institutions. And the rigid regime behind these bars can now be observed in CNA’s groundbreaking four-part documentary, Inside Maximum Security.

The first episode attracted over a million views on YouTube in just four days, and the series also trended at number one on YouTube.

Because for the first time ever, these inmates reveal their identities on camera to tell their stories — an unvarnished look at their lives of crime, their stint in jail as it unfolds and their battle to reform.

LIFE IN LOCK-UP

Boon Keng and Khai are being held in Institution B1, one of the maximum-security institutions. It houses about 500-plus inmates — out of Singapore’s inmate population of about 11,000 — and includes those with long sentences and recipients of violence intervention programmes.

The cells in B1 are all single cells, whereas in other parts of Changi Prison, there are cells holding three, four or eight inmates.

“We don’t want any unnecessary conflicts. That’s one of the reasons why we house them in a single-man cell,” said Jim Ang, the housing unit’s officer-in-charge.

That is part of what makes prison life hard for Khai, because of “that loneliness when you can’t express yourself, when you need to talk someone”. “You’re stuck,” he said.

Or as Singapore Prison Service (SPS) senior personal supervisor Muhammad Shalih Mahli put it, “It can be psychologically small, in a way, if you’re cooped up here for a very long time.”

The impact is especially felt at weekends for inmates who are not involved in rehabilitation programmes, as they may be locked up for 48 hours.

WATCH: How tough is Singapore prison life? | Inside Maximum Security — Part 1/4 (46:09)

“Knowing that your perimeters are only this much (for 48 hours) really disturbs the mind and body,” said inmate Rusdi, 33, who was in prison for the fourth time.

The cell measures seven paces by five paces, as Boon Keng is wont to count when he is bored. Usually, it also gets “very hot” inside, he said.

Showers are taken stooping over a squatting toilet pan. And the CCTV camera in each cell can capture everything inside, including the toilet area.

“If they go to the toilet … if they were to take a shower, we can see everything,” noted Shalih, adding that the CCTV is also equipped to monitor the cells during the night.

Of all the items issued to inmates, the most important ones, cited Rusdi, are the two blankets. They can be used as a pillow, or as cushioning if the straw mat on the ground is too hard for sleep.

For Boon Keng, what is hard to take is the food and the way it is distributed, which is through a food ledge — a low aperture in the door that is opened for inmates at mealtimes.

“The way we’re being served is like being treated as pets in the cage,” he said.

The food is packed in covered trays and placed in food trolleys that are meant to keep the food warm until it reaches the inmates. But it is not warm enough for his liking.

“If (I had to) give points — zero to 10 — I’d say maybe it’s zero,” he said, referring to a Wednesday lunch of mee goreng (fried noodles). “Because it’s very cold. Then, sometimes, the mee has also hardened already.

“When I was doing illegal stuff, when the money was (good) … mostly every day I ate in restaurants. So compared to the food now, it’s like one heaven and one hell.

“Usually, after eating, I still feel hungry. The portion for me isn’t enough.”

Taste aside, the food is approved based on a dietitian’s recommendation as noted by Vinod Karikala Sozhan, an SPS work programme officer in kitchen operations.

“The kitchen will ensure that the daily protein and vegetable nutrition requirements are catered for, for the inmates,” he said.

Some inmates do get hungry at night and might store snacks such as fruits, noted prison officer Muhd Asyraf.

But there are limits to how much food — or any kind of item — they get to keep in their cells. This is to prevent trading and smuggling behaviour.

In the case of Khai, who was found to have two apples and an orange during a routine cell search, Asyraf removed one apple also because “it’s been a few days already”.

“We can’t have them keep it for too long,” said the officer. “It’d make them sick.”

His colleague Muhuthan Munusamy added: “We’re very strict, and we’re very observant of these things.”

Too strict, Khai feels. “The hardest part in prison is the control. Maybe if you’re outside you can be in control. But … inside here, I can’t do anything,” he said.

It is like a concrete purgatory, as prisons have been called.

“Our prisons have to be spartan,” acknowledged SPS director of operations Rockey Francisco Jr, “but not an affront to human dignity.

“It is, as you can see, bare, it’s simple, but at the same time, prison conditions have to facilitate rehabilitation.”

They must also maintain discipline and security, hence the cell searches.

Items deemed to be contraband include string — which, if long enough, might be used in a suicide attempt — pencils and unauthorised paper material, which inmates could use to send messages, within their housing unit or across the prison.

Graceson, a 36-year-old inmate, once managed to get some of these items — a staple from a magazine, charcoal pills given for diarrhoea, and thread to absorb colourant derived from the pills — to tattoo himself.

The former secret society member did not care about the consequences at the time.

“I didn’t hide (the tattoo) properly, then the officer saw it — it was like a fresh wound — so they caught me. My date of release was extended for 21 days, and (the punishment included) four strokes of cane,” he said.

“Four strokes, I think, are nothing.”

Tattooing in prison is a major charge, and boredom is not the only reason inmates break this rule.

“They don’t have the proper facilities to do those tattoos, so they improvise. And I’ve seen infections, their whole hand being swollen,” said Francisco. “That’s one of the reasons why we want to curb it.

“The other aspect is inmate subculture: A lot of our inmates are affiliated to gangs. So usually, some of the tattoos they want to do are gang symbols, and that can be problematic. And that can affect the good order and discipline of the institution.”

In prisons, there are also minor charges, which range from quarrelling with another inmate, disobeying an officer’s instructions to keeping excessive or modified items.

Boon Keng was given a written warning after one such offence: Each cell should have three hooks, but he had improvised extra ones, for example using straws, to hang his clothes.

While he acknowledged the breach, he also did not disguise his feelings about these cell searches. “When I hear (it’s) my turn for a cell search, I feel very sian (frustrated),” he said.

What he finds “humiliating”, however, are the strip searches.

When inmates — who do not get to wear underwear in prison — step out of the cell to attend a programme or go for their twice-weekly yard time in a recreation hall, they must strip and give the officers their clothes.

“The officer will just do a quick rub-down to make sure that they don’t try to hide anything in their clothing and also to check whether the inmates have any injury,” said Ang.

This is for the safety of inmates and officers, added the superintendent.

Each time, though, Boon Keng feels like a prostitute, in his words. “We’re no different,” he said. “We have no choice.”

TRYING TO KEEP BONDS FROM BREAKING

Boon Keng was 18 years old when he was first incarcerated. “There was no law in my life,” he said. “Whatever I wanted, I just reached out (for it) myself. I was the rules and the law.

“Because I was on drugs, when I was short of money, the easy way out was … theft.”

At the age of 21, he was sentenced to 16 months’ jail and two strokes of the cane for harassing debtors and attempting to cause annoyance as a loan shark runner.

He was on drugs again when he committed his latest offences. “I was facing divorce. Then my mum also got cancer. So maybe I didn’t know how to handle my emotions,” he said.

Boon Keng now wants to “seek forgiveness from a lot of people”. One of them is his ex-wife.

“How are you doing out there? Everything been fine for you? How’s our daughter? What school did she get into? Does she miss me? Are you still very angry (with) me?” he wrote in one of his letters to her.

“I want to apologise for my past words and actions, which have hurt you.”

WATCH: Coping with family problems while in prison | Inside Maximum Security — Part 2/4 (46:08)

There has been no response since he was jailed. “Maybe she doesn’t want me to be in contact with my daughter too,” surmised the inmate, whose “only support” and visitor is his girlfriend now.

He used to take his daughter out every weekend if he could, to make her happy — a restaurant here, a bouncy castle there. The guilt he now feels as a father is matched only by his regret as a son.

In October, he was in the day room right outside his cell for his out-of-cell time — which is typically at least an hour daily — when he saw something in the two-week-old newspapers: His mother’s photograph on an obituary page.

“I couldn’t believe it was my mum, so I flipped the (pages), trying to tell myself it was something I saw wrongly,” he recounted. “But after that, I turned back (to the page).

“At that point in time, immediately I went to one corner. I couldn’t control (myself). I cried.”

While he was no longer in regular contact with his siblings, he had contacted his mother in July. Her last words to him, he remembers, were that she would visit him.

“My biggest regret is that I never really told her I love her a lot. I wish I could’ve been a good son to her,” he said.

Because of drugs, I lost my mum and I lost custody of my daughter, so I told myself I don’t want to fail again, for these two people.”

Graceson, who is back in jail for the fourth time, is another who knows he is in the last chance saloon.

He is serving a sentence of six years and five months, with 21 strokes of the cane, for drug consumption, criminal intimidation and carrying three different weapons on three different occasions: A samurai sword, a parang and a bread knife.

He has been in and out of prison since 2009, when his wife, Elaine Ang, first got pregnant a year after they had married.

Inmates are allowed two visits every month, which can be via teleconference and a face-to-face meeting. And she hardly missed a visit back then, he recalled.

“Only twice, because she needed to give birth and bring my eldest daughter for a check-up,” he said.

But this time, not only did she miss visits, she also mentioned divorce in a letter to him.

“I was, like, stunned. I didn’t know how to answer her,” he said. “I’m left with just one year plus (in jail) … If (she) wanted to do this, might as well have done this when I was just sentenced.”

It was unbearable to think, as he did sometimes, that maybe his wife was with someone else. He approached an SPS psychologist for help. He needed to ask what he should do for the marriage.

The answer came from his wife herself, during a tele-visit he did not think would happen following her letter. And it came with a reprieve for him.

“She’s afraid that I might not change, so if I go out and I can’t change, then she’ll definitely leave me, she said. This is my so-called last chance,” he shared.

“I also understand. If I’m the one outside, I don’t know whether I can wait so long. But for now, she’s willing to wait and give me a chance — one more chance — so I feel happy about it.”

With remission for good behaviour, he could be freed in November. But until then, being inside is like being in “a pressure cooker”, noted senior psychologist Rashida Mohamed Zain from the psychological and correctional rehabilitation division.

“If there are other issues that (inmates) encounter, for example problems in the family, it’d result in pent-up frustration or extreme sadness that they may not be able to know how to express,” she said.

“What we do is to help them to talk about these things, at least releasing a little bit of this pressure so that they can function normally.”

Imprisonment is, as Francisco put it, “not about keeping them in” but about “preparing them to return to their community”.

“If the family is intact and supportive and welcoming for the inmate, it gives them a better chance of staying crime- and drug-free,” added the 45-year-old, who holds the rank of assistant commissioner.

Nowadays, prison officers are also more aware of issues that inmates have.

“Previously (inmates) didn’t share anything with the officers. The moment they came inside, they saw the blue uniform — for them, it was like the enemy,” said Muhuthan, a personal supervisor.

“But now it’s changing. They’re sharing a lot of things.”

There are about 20 inmates under each personal supervisor. Typically, Muhuthan interviews them once a quarter. “But sometimes, when the inmates have issues, they can come and request to see us anytime,” he said.

This was how, during conversation with Khai, it emerged that he was struggling emotionally without any visitors.

Visits work this way: One visit card per inmate is issued to a main cardholder, a family member aged 21 or over. Children can then visit inmates if accompanied by an approved adult visitor or a social worker.

This means Khai’s daughter needs an adult cardholder before she can visit.

Inmates can also request phone calls to deal with family emergencies. And to help Khai, Muhuthan granted him a call to his mother.

But it ended in dispute, said the inmate, after his stepbrother and his stepbrother’s wife “jumped in” on their phone’s loudspeaker. “Why don’t I have a family who’s understanding?” he lamented. “The 10 minutes … just went to waste.”

MAKING A BREAK WITH THE PAST

It was an argument, too, that led to Khai’s latest incarceration.

His father had a doctor’s appointment, and they were supposed to meet up with his then girlfriend, but she never turned up, he narrated. “That’s what led me to frustration, anger,” he said.

“She replied after a few days. She said she was going to explain everything to me. She said that she was on the way. That was around 5:30 p.m. I just kept waiting at that MRT station. She turned up at 9:30 p.m.”

Eventually, he became very heated and “grabbed her to show (her) the pain, the struggle” that he had gone through.

“I felt good,” he admitted. “After time (has passed), I understand myself. It’s not worth it. That’s something new that I learnt.”

He and other inmates had learnt during a schema class to be aware of how their past affects their behaviour.

A schema, in psychology, is an entrenched belief that people have of themselves, others and the world around them, which can be formed by childhood memories and adult experiences.

“If hitting someone else was rewarding in the past, that increases the chance of using violence in the future,” Rashida cited as an example.

“For Khai especially, there were repeated times when he used violence to get what he needed. And if it worked, it’d further strengthen that belief that … ‘violence will solve my problems’. After a while it became like … an automatic response.”

What SPS psychologists try to do in these classes is “address what’s really an issue that’s driving the violence” and then teach the inmates to “challenge or accept these thoughts so that they’ll come up with a more balanced perception”.

WATCH: Inside Maximum Security — Episode 3: Breaking bad habits (46:31)

Inside Maximum Security_2021_0_3_Breaking Bad Habits

This module is part of the violence intervention programme for inmates who need it. The activities include mindfulness exercises, which teach them to focus on what they can see, hear and feel. These exercises are meant to alleviate anxiety.

To also help inmates in the programme manage their emotions and behave well while in prison, they can earn points as a group. At the end of each week, these points can be exchanged for privileges, which range from extra time outside their cells to movie screenings.

Usually, they get to watch a film once every three to four months, said Boon Keng, and it is “nicer than watching (one) in the cinema”. He added: “Maybe this is where we’ve lost something, then we appreciate something.”

Each inmate is also awarded up to 20 points a month for good conduct, which can be accumulated and exchanged for privileges such as photos, extra visits and snacks.

“Photos are very precious here,” said Graceson. “You have to accumulate 60 points for one photo.”

Another form of rehabilitation for inmates is work. Prior to incarceration, many inmates did not hold stable jobs, so work programmes help to instil good work ethic and discipline.

In the central kitchen for Changi Prison’s cluster B, for example, lunch and dinner for officers, volunteers and inmates — about 7,000 to 8,000 meals per day — are prepared by inmate workers, guided by chefs from the Singapore Airport Terminal Services.

Here, tools such as kitchen knives are chained up for safety, “and we’ll see who’s suitable for which location”, said Vinod.

“Let’s say the veggie cutting area requires a lot of cutting and grinding, so we need inmates here with the correct composure and the correct mind to perform this type of task.”

Inmate workers are paid once a fortnight. A portion of their salary will go towards their savings, and they can use the other portion to buy canteen items ranging from snacks to scented soap.

Graduands of violence intervention programmes who display good conduct and are a good influence on other inmates can be hand-picked to work as peer facilitators. They are trained by psychologists to assist in programme activities.

Rusdi, for example, was a peer facilitator before he was transferred to a pre-release programme about a month before his release date.

“He’s a very good inmate. But that doesn’t mean all the good inmates are good citizens,” said his supervisor, Muhuthan. “We have a lot of experience where the inmates obey, but after two months, they come back.”

Rusdi knows this all too well. “After my first incarceration, I still thought that drugs weren’t so addictive, thinking that you have the choice to use them or not,” he said.

He was a fitness trainer “living the high life, a luxurious life”. He added: “People want to get a car, to get a bike, to get a house, to get every single thing — I managed to get it all done before I even hit 30.”

But he was getting things done by depending on crystal methamphetamine, also known as ice. The strong stimulant drug is highly addictive and can lead to psychosis or even death.

His latest jail sentence of three years and four months was given after he had trespassed on the grounds of the Istana, high on drugs. When he was caught, he was also carrying a drug utensil.

“For this release (from prison), I need to tell myself that I can’t use (drugs) at all,” acknowledged Rusdi, who managed to keep focused on high-intensity interval training during his two-hour yard sessions, along with some other inmates.

The majority of the inmate population are drug offenders, Francisco noted.

“They come in with certain lifestyles, and they’re scrawny,” he said. “But once they go out, they’re fit because of the food they eat, the time they spend exercising. That’s the irony.”

A number of inmates also get out of prison benefiting from an education thanks to the Prison School. Around 600 to 800 inmates apply annually to study there; about half of them get selected.

Prison School inmates have access, for example, to the secondary school academic curriculum, which is compressed into one year — which means “they’re very busy (and) have much less free time” than other inmates, said Superintendent of Prisons Wong Jin Wen.

“Median sentence is about three to five years, so if we let them study a compressed syllabus … we allow more inmates to benefit.”

One of them is 41-year-old Iskandar, serving his fifth incarceration. “This time round, I don’t want to waste time in prison. I choose to study because in future, with certificates, it can help me get a better job,” he said.

He almost did not get this chance. Apprehended in possession of 35.31 grammes of diamorphine (or pure heroin) in 2012, he faced the death penalty for drug trafficking.

“I was petrified,” he recalled. “I really thought I was going to die. I even made my will.”

His trial was held in three tranches between January 2015 and June 2018. “My counsel really worked hard, because he was trying to create reasonable doubt … to reduce the sentence,” said the inmate.

“I already told him I didn’t want to go the gallows.”

In the end, he was sentenced to 25 years’ imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane for drug trafficking, drug possession and consumption. He was held in maximum security before he was transferred to Prison School.

He has moved on to take his O levels and intends to take a diploma in logistics and maybe a degree after that, all in Prison School.

“I believe I’m a bright student,” he said. “Unfortunately, I tend to (make) mistakes in my life.

“If I wasn’t given a second chance … maybe I’d be hanged already, I’d be dead by now. So when I have this opportunity, I’ll use it wisely.”

Singapore’s recidivism rate has been reported as among the lowest internationally. But for those who reoffend within two years — like the 22.1 per cent of the 2018 release cohort — this is a snapshot of what life may be like.

WATCH: Life behind bars: In prison for the 10th time (5:56)

They still hope that a better version of themselves will prevail eventually.

“This time, I feel that I really need to change,” said Boon Keng. “Because I’m tired of coming back.”

Watch the documentary Inside Maximum Security here. The final episode airs on Sunday, Feb 6, at 9:00 p.m.