Commentary: Taliban’s return in Afghanistan cements Southeast Asia extremist strategy of 'strategic patience'

The Taliban’s recapture of a country provides a new icon of success for global extremism. Its narrative of rewarded perseverance is fuel for terrorist groups here, says counter-radicalism expert Jolene Jerard.

SINGAPORE: The Taliban has an often used Afghan adage to describe its shocking take-over of Afghanistan: “You have the watch, I have the time”.

Then, a reminder of temporal foreign presence in Afghanistan, today that phrase echoes the vindication that perseverance in waiting for an opportune time to initiate a comeback can pay off.

Despite 20 years of occupation by US and allied forces and their technological-military superiority, the Taliban’s return was swift and decisive.

Perhaps it sensed a vacuum created by the US’ capricious policies – with the rushed Doha peace agreement in 2020, the announced pull-out by September and the US desire to press on with withdrawal despite the Taliban’s ratcheting up of civilian attacks and targeted assassinations to intimidate civil society, highlighted by a United Nations report in February.

AL-QAEDA NETWORKS WILL BE STRENGTHENED

Afghanistan’s return to the extremist fold could be the watershed in what may be a global resurgence of transnational terrorism and radicalism.

Specifically, the Taliban’s victory may have a ripple effect on Southeast Asia’s security landscape emanating from the safe havens it may provide Al-Qaeda and other like-minded terror and extremist groups with.

A UN Security Council Report in 2019 had warned of Al-Qaeda’s potential comeback if Afghanistan fell to a resurgent Taliban.

Al-Qaeda members have acted as military and religious instructors for the Taliban. Through the years, their ties strengthened with inter-marriages and shared goals among a second generation of fighters.

Though driven underground since the Taliban’s fall in 2001, Al-Qaeda sees Afghanistan as a critical base of operations, with this relationship likely more pronounced in the coming months.

RIPPLE EFFECTS FOR EXTREMISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

This is a sobering backdrop for Southeast Asia where historical links of Southeast Asian extremist groups with Afghanistan and Al-Qaeda are giving way to rising fears of militant movements being reinvigorated with fresh support.

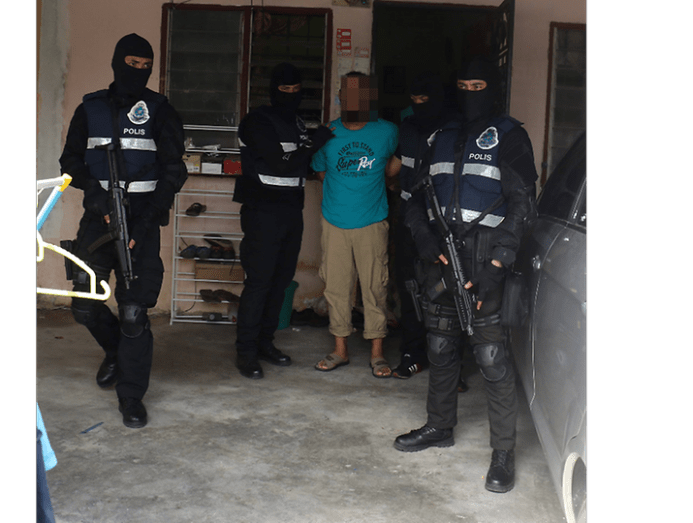

Among the 5,000 prisoners freed by the Taliban after storming a US airbase facility last week were seven Indonesia fighters who had join Islamic State in Afghanistan.

They may now join ranks with groups in Afghanistan and reach back to support and recruit through social media and encrypted messaging.

With the Taliban now armed with helicopters, drones and ammunition seized from the fleeing Afghan military, US officials have expressed concerns this arsenal could find its way elsewhere.

Afghanistan has a longtime psychological hold on Al-Qaeda aligned Jemaah Islamiyah, who had recruited and sent several batches to Afghanistan for training during the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1970s and 1980s.

Among them include Riduan Isamuddin alias Hambali, the mastermind behind a string of bombings and attempted attacks in Southeast Asia and the organisation’s key point man to Al-Qaeda who facilitated Afghanistan training.

His formal arraignment by a US military commission in Guantanamo Bay on Aug 30 could spark a wave of retaliation by newly emboldened Indonesian extremists.

Abdurajak Janjalani, founder of the Abu Sayyaf group in the Philippines, also fought in the Soviet-Afghan war when Osama Bin Laden led the charge.

These common combat experiences in Afghanistan have left an indelible mark and established them as an alumni network of Southeast Asian Afghan fighters.

PRAISED BY AL-QAEDA ALIGNED GROUPS

It comes as little surprise then that Al-Qaeda aligned groups have not shied away from expressing solidarity with the Taliban.

These links are likely solidified through both personal networks and institutional affinity given shared history and ideology.

Jemaah Ansharu Syariah (JAS) through its spokesman, Abdul Rochim Ba'asyir, son of Abu Bakar Ba'asyir, co-founder of Jemaah Islamiyah, called on Muslims in Indonesia to support this “momentous victory” of Afghanistan’s freedom from “a puppet government”.

Abdul Rochim was a former media committee member under Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, the operational planner for Al-Qaeda. He was among the first to issue an official congratulatory statement to the Taliban.

MIXED REACTIONS BY ISLAMIC STATE-ALIGNED GROUPS

Centinel’s research shows that Islamic State aligned groups in the region have had mixed reactions, with some in the Philippines echoing calls for the groups in Mindanao to follow in its footsteps – highlighting that the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters could learn from the Taliban.

Meanwhile, Islamic State-aligned Indonesian supporters, who have witnessed the Islamic State’s takeover of territories in Iraq and Syria, prefer to take a wait-and-see approach to assess the Taliban’s ability to cement its hold and implement Shariah law to its fullest extent.

While the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and are all radical terrorist groups, they differ on some interpretations of doctrine and ideology. These differences have caused disagreement and schisms.

The Islamic State critiques the Taliban for its focus on a national Afghan agenda as opposed to a global one, the Taliban’s protection of Shi’a communities whom the Islamic State detests on ideological grounds, and there are ongoing clashes between the Taliban with the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) – the Islamic State branch with a presence in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

REVIVAL OF A STRATEGY OF STRATEGIC PATIENCE

And yet, rather than financial, training or even military support, the strategic value of the Taliban’s victory lies in the example it has set in playing the long game. COVID-19 restrictions on travel impede aspiring fighters from moving to Afghanistan in the immediate term.

In reconquering an entire country, the Taliban accomplished that which the Islamic State could not. In overturning the government, it has encouraged extremists with hopes of establishing a caliphate some day by showing that enemies can be beaten back with sufficient planning and patience.

Groups in the region may be emboldened by this new narrative of success, one that speaks of the reward for perseverance despite a dire outlook, and some semblance of assurance of divine intervention culminating in victory over the enemy.

A graver challenge lies in whether any ideological convergence between the Taliban, Al-Qaeda and Islamic State can spark new incarnations here. Warning of the global security fallout with the Taliban at the helm, the UN Security Council assessment in 2019 also noted that the Taliban partnered with nearly “20 other regionally and globally focused groups” in Afghanistan.

Despite the failure of Islamic State groups to conquer Marawi in 2017 and the limited effect recent bombings in Indonesia have had in advancing their cause, the Taliban’s win in Afghanistan can act as a new source of inspiration.

For Southeast Asia countries that have shored up counter-terrorism capabilities, the Taliban’s win reminds us of the limitations of conventional military force in exterminating extremism.

The Taliban’s takeover is a poignant reminder that the region must remain resolute in continuing efforts to blunt extremism and mitigate its effects.

At a time when the pandemic has wiped out some livelihoods and endangered most others, countries should also bear in mind how extremist groups saw new openings when social support were strained like in the Asian financial crisis.

Dr Jolene Jerard is Executive Director at Centinel, a public safety and management consultancy firm. She is also Adjunct Senior Fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.