Commentary: Conditions may be ideal for Russian military to implode

The Russians are already experiencing low morale and a lack of troop cooperation only a few weeks into the conflict, says a professor.

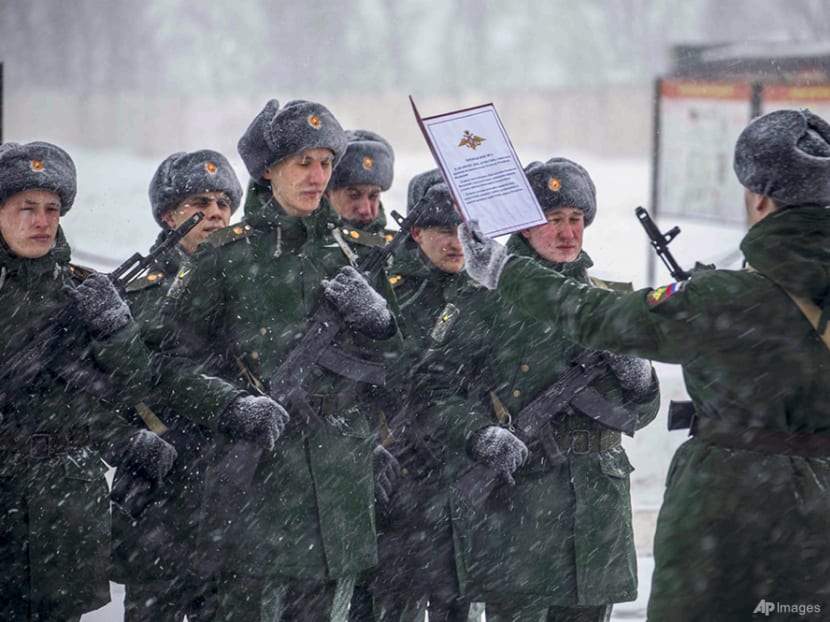

In this photo released by the Russian Defense Ministry Press Service on Jan 22, 2022, servicemen of the engineer-sapper regiment take the military oath in the Voronezh Region, Russia. (Russian Defense Ministry Press Service via AP)

ESSEX, England: Reports have emerged in recent days that Russian troops in Ukraine, stalled in their advance and suffering numerous military setbacks, have sabotaged their own equipment, refused to fight and carry out orders, and even, in one report, run over their own commander.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) estimates that as many as 15,000 Russian soldiers may have been killed in less than two months of fighting, or the equivalent of all of the Soviet soldiers killed in nine years in Afghanistan.

Morale is reportedly incredibly low. In this situation, the conditions are ideal for the Russian military to implode.

While desertion (leaving one’s fighting unit) can undermine a military physically and psychologically, defection (joining the enemies’ forces), which Ukraine is trying to encourage Russian troops to do can offer the enemy crucial insider intelligence, which may help the Ukrainians gain the upper hand.

RUSSIA’S ABYSMAL RECORD OF RETAINING SOLDIERS

This wouldn’t be the first time that Russian or Soviet troops have refused to cooperate with orders in a conflict. During the Russo-Japanese War, Russian troops on the battleship Potemkin famously mutinied in June 1905.

Much of the Russian fleet had been destroyed in the Battle of Tsushima the previous month and the Russian navy was left with some of its most inexperienced recruits. Facing deplorable working conditions, including being served rancid meat, 700 sailors mutinied against their own officers on one of the most powerful battleships in the world.

During World War II, Joseph Stalin tried to ensure troop obedience by implementing a zero-tolerance policy towards surrender. “Order number 227”, issued in July 1942, dictated that any soldier who retreated was to be immediately killed by special units.

By some estimates, these units killed as many as 150,000 of their own troops. And yet, no other Allied army had as many defections, with over 1.4 million Soviet prisoners of war choosing to fight alongside German soldiers.

Several decades later, the USSR’s conflict with Afghanistan brought further challenges for the Red Army. The Soviet army comprised conscripts who had no training in guerrilla warfare and felt little identification with their mission.

Draft resistance among recruits from the Central Asian and Baltic republics was common, even though draft dodging was a serious crime. Many Soviet soldiers were disillusioned with the atrocities which they were forced to commit against innocent civilians.

Desertion was also widespread in Russia’s first conflict with Chechnya from 1994 to 1996, where many were sent to fight in one of the harshest conflict environments without ever having fired a shot in training.

LOW MORALE, LACK OF PAY, LITTLE TRAINING

Defection and desertion in combat are common. Eventually, wartime hardships, poor combat performance and a waning ideological commitment to the cause can spur troops to jump ship. But the Russians are already experiencing low morale and a lack of troop cooperation only a few weeks into the conflict.

Research suggests that morale is especially low in militaries that have been de-professionalised. In spite of reports that Russia’s army was attempting to reform its structure, Russia’s own military reported in 2014 that more than 25 per cent of its personnel could not operate their infantry equipment.

Though the overall budget for the military increased as a result of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s reforms, pay for troops did not. Contract soldiers (who sign up for a period of three years) are paid 200 per cent less than their United States counterparts, at about US$1,000 a month, while the conscripts are paid only US$25 a month and receive little training.

All of this contributes to low morale and raises the risk of desertion and defection.

RUSSIA’S DESERTION WOES WILL WORSEN

To deal with low troop morale and potential desertions, Russian generals were moved to fight on the front lines to motivate troops that are, at best, indifferent to the conflict. Such little trust in junior officer corps has led to poor battlefield initiative, and greater communication, command and control problems.

As a result of generals having to fight front and centre, at least seven generals have died, the highest death rate of generals in the Russian military since World War II.

With possibly up to one-fifth of Russia’s original invasion force “no longer combat effective”, Putin has ordered another 134,000 conscripts, aged 18 to 27, who may have little idea what they are getting themselves into.

But reports continue to emerge of Russian conscripts feeling as though they have been duped into fighting. They are open to anti-war messages, which Ukraine’s intelligence agencies are trying to exploit.

Not only has Russia failed to win over the hearts and minds of the Ukrainian people, but it now appears to be struggling to win over the hearts and minds of its own military.

Natasha Lindstaedt is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex. This commentary first appeared in The Conversation.