Commentary: Why didn’t India take home more Olympic medals?

It was India’s best Olympic showing to date, but why wasn’t it near the likes of other major countries like China and the US? Aarti Betigeri explains.

Gold medalist Neeraj Chopra, of India, at the medal ceremony for the men's javelin throw at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Sat, Aug. 7, 2021, in Tokyo. (Photo: AP/Martin Meissner)

CANBERRA: India took home seven medals, including one gold, from this year’s Tokyo Olympics.

There have been two reactions: The first is, amazing! India has taken home its largest-ever medal haul! What an excellent achievement!

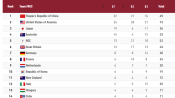

The second is one of dismay over India’s relatively poor performance: How can India, with its 1.3 billion-strong population, consistently fare so dismally at the Games? And worse, when compared to 1.4 billion-strong China, second on the medals tally, with 38 gold, 32 silver and 18 bronze medals?

Both responses deserve consideration given the confounding situation of India at these Games. The world’s second-largest population is 48th on the list of Olympic medal-winners.

INDIA’S BEST OLYMPICS SHOWING EVER

Those who think we should revel in India’s moment of triumph aren’t wrong about the reasons for celebration.

Indeed, The Guardian labelled Tokyo “India’s greatest ever Olympics” after 23-year-old Neeraj Chopra won big in the men’s javelin event, throwing 87.58m for India’s first gold in athletics.

The gold elevates Chopra to an elite club of the very few. For an army soldier and the son of a village farmer in rural northern India, his win is an extraordinary personal achievement that has also become a symbol of hope for future sporting prowess for the country.

India’s medal tally in this Olympics was its best showing since it began competing in the Games in 1900 - a sign commentators have pointed to that recent investments by the government and private companies in sporting infrastructure, training and individual athletes are paying off.

From one gold and two bronzes in the 2008 Beijing edition, to two silvers and four bronzes in London in 2012, and two medals in Rio, India’s quest for medals has been on an uneven but somewhat steady increase.

And yet one cannot help but ask why India does badly at the Olympics when it has produced otherwise world-class athletes.

It is home to Asian Wrestling Championships winner Vinesh Phogat, decorated archer Deepika Kumari and Boxing World Cup gold medalist Amit Panghal, all of whom are world number ones in their sport or category.

Part of that problem lies in larger economic, social and even spatial forces that rule over life in India, and the realities that large, well-endowed rich countries simply win more sporting medals while developing countries have other priorities.

Many other developmental indicators, such as the health of the general population and the country’s infrastructure in terms of roads and bridges, also strongly predict Olympic success, a study by The Economist examining Olympic medals won since 1960 published this week shows.

And so scale is hard to achieve. India may be the world’s fifth largest economy, but by and large remains a developing country, compared to the likes of the advanced economies of the US, UK and Japan or a rising China, and falls behind on such indicators.

WHY THE DISMAY OVER INDIA’S MEDALS HAUL

At the same time, India has traditionally neglected and underfunded its sporting sector.

Thankfully while the Indian government in January cut the overall sports budget by more than 8 per cent, it has a special fund, the Target Olympic Podium Scheme (TOPS), in place since 2014 to support about 160 athletes today financially in their quest for Olympic glory.

Private companies, like major sponsor life-insurance company Edelweiss Tokio, have also stepped up sponsorship of high-performance sports, supporting Team India’s attendance at the Tokyo Olympics, and tapping on rising stars to become faces of their brands.

Scholarships to incentivise and support the young on their Olympic journey, under TOPS or otherwise, hold the keys to unlocking India’s sporting dreams.

In India, would-be athletes are stymied by poor nutrition, inferior living conditions, not to mention a lack of access to facilities, kit and equipment and even social pressures around gender and class that might preclude many from being included in sports.

Rani Rampal, captain of the women’s field hockey team, put it best in an Instagram post.

“I wanted an escape from my life; from the electricity shortages to the mosquitoes buzzing in our ear, from barely having two meals to seeing our home get flooded.” She began her journey practicing with a discarded broken hockey stick at a nearby hockey academy, unable to afford a new one.

Then there is Deepika Kumari, the world number one in women’s archery. Born to a rickshaw driver father, she grew up stealing tamarinds and bathing in the river when her village home had no bathrooms.

She has even revealed at one point that she and her family would often sleep with their stomachs empty. Both have been beneficiaries of India’s sporting scholarships and were close to securing a podium win this time around.

The TOPS scheme is a clear sign of India’s willingness to invest in its future Olympic sporting stars, and the recognition of the deep wealth-income divide that would otherwise keep talented players away from the field.

There is of course one sport that commands the most attention and resources in India: Cricket.

Cricket is treated with an almost religious fervour, far from any other sport, although a nascent soccer league is starting to gain traction.

The gentleman’s game has morphed somewhat on the subcontinent, with the Indian Premier League assuming the powerful status of the US Super Bowl, complete with teams, cheerleaders, and lots of flash and colour.

It has also brought enormous money to the game. The Indian cricket board, the BCCI, in January was valued at more than US$2 billion, tripling in value in just five years, with a large chunk attributed to the IPL.

Indian national cricket captain Virat Kohli earns up to US$3 million each year, not counting commercial endorsements. So it’s little wonder India will be pushing for the sport’s inclusion in the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

Hockey is traditionally India’s national sport, but has received relatively scant attention, although has benefitted from recent investment in various states, such as the Odisha government funding a new Astroturf field.

Still, the small wins in this Olympics may be a sign of better times to come. India’s sporting prowess in hockey had languished for years despite winning most of its medals in this sport - including eight out of its total 10 golds.

And yet, in Tokyo, the Indian women’s team beat Australia to reach the semi-finals, coming fourth overall, while the men’s team took the bronze - the team’s first medal in over 40 years.

Success could also beget success. Neeraj Chopra’s gold may be a shot in the arm for would-be athletes across the country, that drives further investment and resources.

So those seven medals might sound scant, but potentially represent real achievement against the odds, and an indication that India’s time on the podium may be coming.

Just give it a few more Olympics.

Aarti Betigeri writes on India issues as a journalist based in Canberra.