Commentary: Why normally decisive parents worry about vaccinating young children against COVID-19

Parents see themselves as protectors and need more reassurances when deciding for their children instead of for themselves, say NTU Centre for Information Integrity and the Internet’s Edson C Tandoc Jr, May O Lwin, Akshar Saxena, Kim Hye Kyung and Goh Zhang Hao.

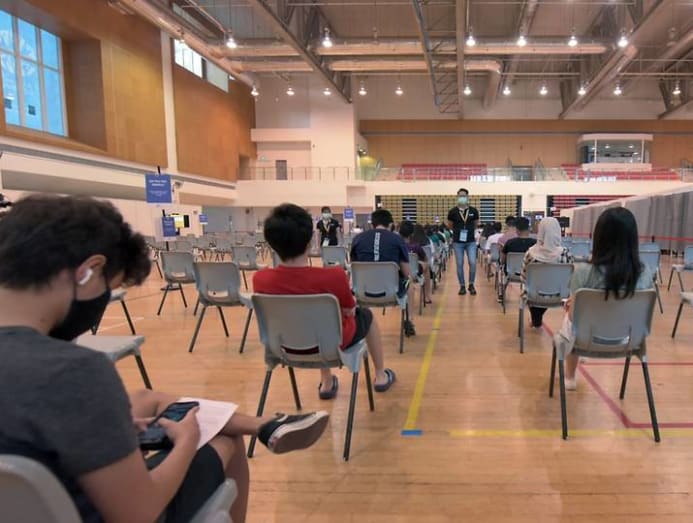

SINGAPORE: Singapore hopes to extend COVID-19 vaccines for children aged five to 11 from January 2022, said the Ministry of Health (MOH)’s director of medical services Kenneth Mak on Saturday (Nov 20).

It was probably only a matter of time – after countries like the United States and Israel approved the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for use in that age group earlier this month.

However, numerous opinion polls there show one-third of parents will get their kids vaccinated right away, and another one-third will adopt a “wait-and-see” approach.

Parents seem more unsure about vaccinating younger children, even if they were eager for themselves or older children aged 12 and above. Five out of seven students in Primary 6 to Secondary 3 signed up within the first week of being invited to do so in June.

On CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast, a mother of three described a “niggling fear” despite published data and professional reassurances.

Comments on social media and messaging app groups reveal common reasons for the apprehension: Possible side effects and whether the risks outweigh the benefits.

Some argue kids are “not likely to be severely affected” pointing out children accounted for only over 8,000 cases out of 250,000 cases reported in Singapore.

Others continue to claim a 2-year-old died during a Pfizer-BioNTech US trial — a falsehood debunked by fact-checkers.

MORE RISK AVERSE WHEN DECIDING FOR CHILDREN

Studies have found parents tend to be more risk-averse, especially on physical safety and health, when deciding for their young children than for themselves.

Parents tend to overestimate their own health but become overly cautious as protectors to vulnerable children – especially since pre-adolescents are less able and motivated to decide for themselves, compared with adolescents who likely participated in the decision to get vaccinated.

Thus, making a decision that potentially exposes their young children to harm is unthinkable.

We observed online criticism of those advocating for child COVID-19 vaccination as being “terrible people doing such things on innocent children” or “not human” for not standing up for their children.

Because of risk aversion, we still see concern in various countries about the safety of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccination, despite studies repeatedly showing it doesn’t cause serious side effects as alleged.

Parents may thus put more weight on the COVID-19 vaccine’s risk of myocarditis, a rare side effect that landed a 16-year-old in ICU in Singapore, or on the chance of yet unknown medical implications on their development and growth.

Other studies have found some parents would rather not make a decision – and accept the risk their children catch a disease naturally as “fate” – than actively decide to vaccinate and potentially proactively bring them harm.

BUT LESS BELIEF IN ODDS OF SEVERE INFECTION

Some also believe young children aren’t at risk for COVID-19, and that they’ll recover quickly with no bad outcomes even if infected.

This often undergirds the reasoning for those who believe the risk of side effects from the vaccine outweighs any benefits.

Worried about COVID-19 vaccination for your young children when the time comes? Unpack the data and concerns with experts and a parent on CNA's Heart of the Matter:

In a survey we commissioned at the Centre for Information Integrity and the Internet (IN-cube) involving 1,600 participants in Singapore last year, we found those who see themselves as at-risk for COVID-19 infection were more likely to report higher intention to get vaccinated.

We already observe this with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination - mothers think HPV vaccine is unnecessary if they also think their daughters are at low risk of contracting the virus and prefer a “wait-and-see” attitude.

It’s unsurprising then that some parents may perceive COVID-19 in a similar light.

Other parents also believe since almost everyone else is vaccinated, the risk of their children getting infected with COVID-19 is low – a common argument by those unwilling to get vaccinated.

Such parents feel justified in thinking the risks of vaccination outweigh the benefits, when MOH says that fewer children have been sick with COVID-19 compared to adults - even though some cases have developed serious complications.

They similarly discount other warnings that unvaccinated children can still catch and spread the virus, including to vulnerable populations like the elderly, or that Singapore is seeing a rising trend of infected children below 12 – about 11.2 per cent of all COVID-19 cases on Nov 19, up from 6.7 per cent four weeks prior.

So taking these insights together, even if the authorities seek to reassure the COVID-19 vaccine is safe, parents looking at the same statistics will focus on the few cases of bad vaccination outcomes but discount the few cases of severe infection outcomes.

USING INFORMATION TO CONVINCE PARENTS?

Many of these perceptions are shaped by what parents read and see around them. But the barrage of information – from official news sites and anti-vaxxer platforms - makes it difficult for parents to process.

Some posts we saw shared on messaging apps are real news stories, such as Taiwan suspending second Pfizer doses for those aged 12 to 17 amid concerns over myocarditis that make parents question vaccine safety in younger children.

While articles about the safety of vaccines are also shared, already-hesitant parents may focus only on stories echoing their fears, such as reports of a few experiencing side effects, or posts from overseas anti-vaxxer platforms claiming more kids are “sacrificed” than saved.

Exposure to inaccurate or exaggerated reports can affect parents’ decisions—a previous study found HPV vaccination rates dropped in Ireland and Denmark in 2016 due to false reports about side effects and anti-vaccination lobbying.

In the Philippines, a measles outbreak erupted in 2019 following a political controversy over the use of a dengue vaccine that lowered overall public confidence in all vaccines.

In another IN-cube survey involving 800 participants in Singapore in July, we found participants living with children reported higher levels of news consumption and spending more time on social media than those who do not.

However, information alone may not convince parents to vaccinate their young children.

For example, a US survey experiment found that government messaging debunking claims that MMR vaccines cause autism did not increase vaccination intention among study participants.

While refutations can reduce misperceptions, they may also lower vaccination intention if they instead reinforce risk aversion by reminding parents of potential risks.

UNDERSTANDING, NOT INSTINCTIVELY JUDGING, PARENTS

How parents decide for themselves when it comes to vaccination is different from how they decide for their children. Interventions to encourage people to vaccinate are not automatically transferable when dealing with parents.

First, parents trust health experts they are familiar with and we should encourage them to consult their paediatricians about their hesitation and fears.

Second, parents also tend to trust one another and lose or gain confidence from each other’s experiences. But we tend to approach only those who already think the same way, for example, anti-vaccination groups rarely include the perspective of those with positive experiences.

Third, humans are hardwired to be constantly vigilant against threats. We may thus read and remember more stories of adverse vaccine reactions, even if they represent only a tiny fraction of those vaccinated. According to the Health Sciences Authority, 0.006 per cent of almost 10 million doses administered in Singapore were classified as serious adverse effects as of Oct 31.

So there needs to be deliberate effort to widely disseminate more representative perspectives from parents.

Hearing from young children who got vaccinated against COVID-19 in other countries without experiencing serious side effects may also give parents a more complete picture to guide their decisions.

Who knows if vaccination may eventually be extended even to children below five? There will certainly be more anxious parents.

This anxiety stems from parents caring about their children - taking to heart their role of protecting their little ones. Thus, we must delve deeper into understanding and allaying parents’ fears instead of instinctively judging them.

Edson C Tandoc Jr is an Associate Professor and Associate Chair at the NTU Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information (WKWSCI) and the Director of the Centre for Information Integrity and the Internet (IN-cube).

May O Lwin is the Chair and President’s Chair Professor at WKWSCI and senior advisor of IN-cube. She specializes in strategic communication and health communication.

Akshar Saxena is an Assistant Professor at the School of Social Sciences (SSS) and a committee member of IN-cube. His research focuses on health economics and public economics.

Kim Hye Kyung is an Assistant Professor at WKWSCI, specialising in health communications, and a collaborator for IN-cube.

Zhang Hao Goh is a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at IN-cube at WKWSCI specialising in human cognitive responses and their coping behaviours toward threats.