How KEK Seafood prioritised people over profit during the pandemic – and even opened a new East side outlet

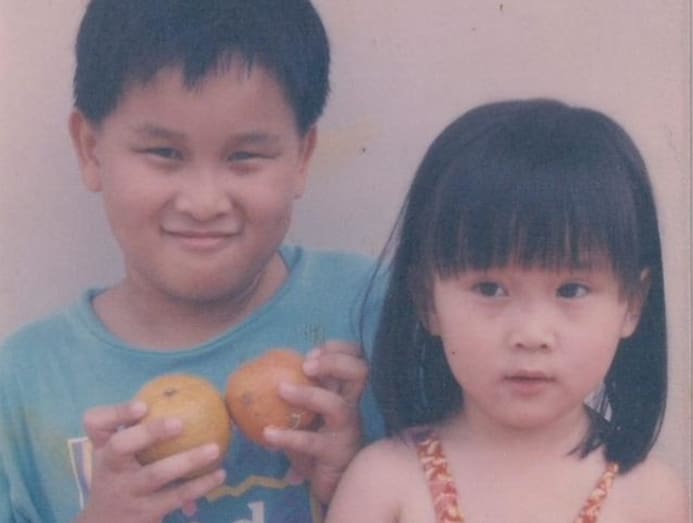

The zi char eatery of humble origins has finally expanded to a second outlet – after expanding their reach across the world by way of being featured by Anthony Bourdain and Netflix. But third-generation owners, Liew siblings Paul, Wayne and Jia Min, are all about keeping it as simple, sincere and close to the family’s bosom as their grandmother’s signature claypot liver.

Liew siblings Paul, Wayne and Jia Min are the third-generation owners of KEK Seafood, the zi char eatery set up by their grandparents in the 1970s. (Photo: Aik Chen)

About two years ago, at the height of the pandemic, well-loved Singapore zi char institution Keng Eng Kee (KEK) Seafood’s founder, octogenarian Madam Low Peck Yah, made a phone call to her grandson, Paul Liew, who’s currently running the restaurant.

That was the period when F&B outlets were closed to dine-in guests and the industry’s survival prospects looked bleak, with many restaurants, cafes and stalls having to let staff go.

His grandmother had only one thing on her mind, and it wasn’t the preservation of her five-decade-old brand, Liew recounted.

“She said, ‘Make sure everybody stays with you. Make sure everybody is all right. That’s how we do our business. It’s not just about profit-and-loss. It’s not just about earnings.’”

Throughout the pandemic, KEK did not lose a single staff member to lay-offs. In fact, “We were able to increase everybody’s pay, and bring back people who were stuck in Malaysia, even at extra cost, because they couldn’t be out of a job for such a long time. We needed to take care of them,” Liew said.

Emerging from the pandemic, they’ve even expanded their business, opening a new, much-anticipated second outlet in the East side – a 140-seat, fully air-conditioned restaurant at SAFRA Tampines.

During the “circuit breaker” period, the Liews – big brother Paul, 41, who takes care of business development; Wayne, 38, the executive chef; and youngest sister Jia Min, 31, the head of operations – realised the importance of making sure their food delivery game was strong, getting online ordering systems in place and tweaking their recipes to travel well.

“Even the older generation, like my parents, see that to survive in a post-pandemic business environment, we cannot do things as we used to. We are a heritage brand, but we need to keep up with the times, while keeping our flavours and values,” Paul said. Today, delivery orders make up about a quarter of the revenue.

In a way, if not for the pandemic, a second outlet might not have materialised.

“We did a lot of deliveries, and through the data, we found that there were a lot of orders from the East.” Even though the food travelled one hour from the eatery at Alexandra Village in the West, there were still repeat orders from the East. “So, we knew there was a potential market there.”

The time is right now, Paul said. And, “It’s also an opportunity for our senior staff to grow” by learning to manage an outlet more independently.

Grandma died in March this year, at the age of 90, having survived her husband. “The last stop that her coffin made was at KEK at Alexandra,” Paul recalled. “It stopped there for a couple of minutes, and all the staff came out to pay their last respects.”

WOK YOUR WORLD

KEK Seafood’s story is almost as well known as their signature Moonlight Hor Fun or coffee pork ribs.

Madam Low and her husband, Koh Yok Jong, sailed from Hainan in China to begin a new life in Singapore, and in the 1970s, set up their zi char stall at Old Havelock Road, choosing a name that referenced their ancestral village.

Of their children, daughter Koh Liang Hong was interested enough in the business to eventually take the reins; she also married one of the chefs, Liew Choy, and went on to have Paul, Wayne and Jia Min. (“My father was tall and handsome,” said Wayne with a chuckle. “They called him Liu Wen Zheng” because he resembled the Taiwanese idol, Paul put in.)

When the hawker centre at Old Havelock Road was demolished, KEK Seafood moved to Alexandra Village, becoming an established name in the local food scene. In 2016, it featured in Singapore’s Michelin guide; in 2017, it was spotlighted in CNN’s Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown; and in 2019, it was seen in Netflix’s Street Food Asia. The KEK team has travelled all over the world representing Singapore in tourism events and culinary collaborations, from San Sebastian to Copenhagen, Busan, Manila and New York City.

“Grandma never imagined that the hawker stall she started for survival would one day be taken overseas by her grandkids,” Paul said. “We used to think that zi char was just humble cuisine, and there was nothing special about it. ‘Hor fun? Eat your hor fun, and that’s all.’ But once we started travelling, we found that people adore it. People respect this kind of cuisine.”

Zi char, in fact, was the original produce-driven cooking, with an emphasis on free styling and making the most of whatever ingredients you had on hand, Wayne opined. “It’s not always the case that a lot of ingredients add up to good food. My dad always told me, ‘I just need soya sauce, sesame sauce and Chinese wine, and whatever I cook, there’ll be no complaints from the customers.’”

Wayne was the only one of the siblings who had an interest in cooking, and as a result, was the favourite of his grandmother – when she cooked Hainanese chicken rice at home, she always saved him all the chicken drumsticks. Under the mentorship of his father in the kitchen, he learned to master the skills of making absolutely everything from scratch, thinking on his feet, and turning even the least premium ingredients into tasty dishes, keeping meals affordable for all.

But it’s not just about taste. “The thing about zi char is controlling the fire – if it’s too large, you get burned; if it’s too small, you don’t get the 'wok hei',” said Jia Min, pointing out that being able to cook at top speed is essential, too. “I feel it’s a gift.”

“Wok hei”, a heady fragrance produced by cooking food in a wok over very high heat, is a flavour that’s “passed on from my dad’s generation – many of the younger generation don’t really know what it is. What they know is a slightly burnt flavour,” said Wayne, explaining that there’s a grey area between the two.

There is no shortcut to achieving the real thing, which is why many cooks’ attempts fall short. “To become a master of wok hei takes years. You need to be trained via every staff meal,” Wayne said. Most importantly, it takes “love and passion in the wok”. “Even if you and I have the same salt, sugar, ingredients and recipe, what we cook might be completely different.”

Although zi char is a traditional style of cuisine, Wayne has introduced new things like combi ovens into the kitchen for steaming and grilling, so that the cooks can focus on dishes that require old-school wok love.

“That’s how I think zi char has evolved – keeping the tradition of how we do certain dishes, but embracing and accepting new ingredients, techniques and equipment,” Paul said.

IN THE BLOOD

The business, needless to say, has evolved through the years, too – but few establishments in Singapore can say they have been family-run for three generations and counting, over a span of 50-plus years.

Growing up, Paul said, “Our parents never wanted us to be in this business.” But, there was always the unspoken understanding that the restaurant was very important to them – and that they didn’t really mean what they said.

“What's funny is that they said, 'Don't come and take over’, but every weekend, my mum would call us and say, ‘All right, don’t take over, but can you come help me during the weekends?’ Or, ‘It’s a public holiday – can you come and help? We’re shorthanded.’”

Because their parents were always working, “Our playground used to be the restaurant,” Jia Min recalled. “Even before we were helping out, when we were four or five years old, we were playing hopscotch at the back of the kitchen.” “And walking live crabs on a string,” Paul added. Even birthday celebrations were held at the restaurant.

“My dad would take me into the kitchen, sit me on top of the under-counter chiller and let me watch him cook,” Wayne said. “I thought I was the only one who got that treatment!” Jia Min piped up.

As they got older, “We were there folding takeaway boxes, watching our parents in the kitchen and serving customers. We knew everyone, even the customers. So, when we grew up, it was not difficult to take over. We’ve been in the business since we could walk,” Paul said.

That’s in spite of the fact that, graduating with a degree in business, “I always thought I would be in Shenton Way, in a long-sleeved shirt, going to have a beer at Clarke Quay after work,” Paul mused. And “I thought I would sign on, because the package was quite attractive,” Wayne said.

“In our teenage years we thought, ‘Sian, every weekend, we have to go back to work.’ But slowly, you see the fun of being able to interact with a lot of people; and then you see how your parents have worked so hard,” Jia Min said. “We figured out that if the three of us were in the business, they wouldn't have to work so hard any more.”

Now, Paul said, “Wayne and I have kids. Many people ask us if we want them to take over. I think, in the same way, even though we are very much a new generation, we say no.” But they find themselves repeating their parents’ behaviour, asking the kids to come and help out. Wayne’s oldest daughter, who’s 21, has taken an interest in the business, and is very good with customers, they shared with obvious pride. “I think with any family business, it’s the same thing – we just want to put it in good hands,” Paul said.

HUMAN CONNECTION

Putting their heart and soul into the restaurant is the Liew siblings’ way of honouring their parents and grandparents.

Paul recalled fondly how, in her later years, Grandma would visit the restaurant in her wheelchair and “be pushed from staff member to staff member to say ‘How are you?’ like a president”. “She wanted to make sure people felt at home, and that they weren’t just staff, they were part of us. From Day One, it was all about family first.”

To this day, KEK puts relationships over profits, honouring the ties built over the years not only with their customers but also their suppliers. Even the plastic bags they use still come from the same local company they have always been ordered from, Paul said.

That’s why, although they have been approached by would-be business partners and received proposals for franchise opportunities, it has taken them this long to expand. For them, it’s about partnering with people with the right emotional connection.

Above all, the most important piece of advice from their dad has always been to do everything with honesty.

“When I buy durians, I always get overcharged. He says, ‘It’s okay. Others can cheat us, but we must never cheat others',” Jia Min shared.

Wayne said he was taught that “in business, everything must be honest – ingredients, quality. Don't do the wrong thing just to save some money”.

One of his fondest memories is of the day Grandma suddenly said to him, “I have something to show you”, and then demonstrated how she made KEK’s famous claypot liver dish in their kitchen at home. “I was so shocked. I had never seen her cook it at home. She was so cute – she asked me to taste it and asked, ‘Is it good?’”

At the new KEK Seafood at Tampines, one of the dishes you won’t find at KEK Alexandra is claypot pork liver with rice mixed into the dark gravy, instead of on the side. That’s how the Liews are used to enjoying the dish at home.

“When we were kids, mum would put rice into the liver dish,” Paul said. “The liver is one dish we are really proud of because we’ve been doing it the same way for 52 years.” And it is his personal favourite. “There are times we get orders wrong – that is one dish I don’t mind the staff getting wrong. I put it aside, put some rice into it and stir, and eat it later. I’m secretly happy about it!”

Other dishes unique to KEK Tampines include claypot crab with vermicelli and garlic; tofu and luffa with sliced fish; and claypot braised duck with yam.

One thing you won’t find on the menu, though, is fried eggs – which happens to be the only thing the Liews’ dad used to crave when he came home from work (Wayne recalls being asked to fry up a crispy egg, and using the lid of the wok as a shield from the oil). Why did he refuse to serve them at the restaurant?

“There are some urban myths in zi char,” Paul explained. For instance, when the restaurant opens for the day, there's a superstition that the first dish sold should never be rice, whether white or fried, so, if a customer asks for that, they’ll be asked to order something else as well. And, “You never serve fried eggs, because it represents business being bad,” he chuckled.

Speaking of egg dishes, there was one Chinese New Year when a customer came in asking for egg fuyong. The kitchen was serving up only their Chinese New Year menu, and egg fuyong wasn’t on it. “But the customer said, ‘My father is dying and wants egg fuyong,’” Wayne recounted. So, his dad made the dish. Now, “The family comes every year on that day to eat and remember their father,” Paul said.

It is connections like these, built and cultivated with diners over the years, that sustain the KEK spirit, Paul told us. “Some diners are three-generation families, like us. My parents have always been very aware of the standards of hospitality we need to keep in place – if not, it will be just another outlet.” He added, “Why has our business lasted 52 years? It’s not only the food – it's the soul of everyone in it.”

KEK Seafood (Tampines) is at SAFRA Tampines, 1A Tampines St 92, #01-K2. KEK Seafood (Alexandra) is at 124 Bukit Merah Lane 1, #01-136.