Meet the math teacher who literally wrote the book on Singapore Malay food

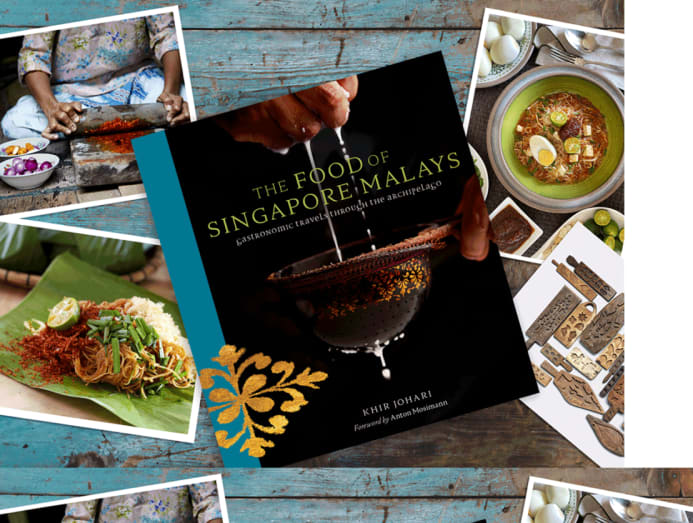

Khir Johari’s The Food Of Singapore Malays gives Singaporeans a proper lesson on the history of our first cuisine.

Khir Johari, author of the book The Food Of Singapore Malays. (Photo: Khir Johari)

He may have written the landmark book on Singapore’s Malay food history, but Khir Johari still describes himself as a “math educator”. Never mind that he hasn’t taught math since 2007 when he left Silicon Valley after six years as a high school teacher. “Once a teacher, always a teacher,” he chirped.

In the years since, Johari has dedicated more than a decade to creating The Food Of Singapore Malays: Gastronomic Travels Through The Archipelago. The behemoth 624-page tome chronicling the history, geography and cultural beliefs that have shaped Malay gastronomy sold out within a week of hitting the shelves last November and is in the process of its second print run.

To paraphrase the book’s publicity pitch, this seminal work is a celebration of the people and culture of the Malay archipelago, interspersed with 32 recipes for key Malay dishes and 400 eye-catching images, mostly by photographer Law Soo Phye. It traces the evolution of Malay cuisine from the 7th century to present day, with Singapore set firmly at the heart of its narrative.

Beyond the glossy spiel, what The Food Of Singapore Malays provides is an opportunity for us to reflect on our country’s history concerning Malays and their food, and to acknowledge them as our region’s first cooks, especially as we devour iterations of dishes they’d introduced to our tables.

GROWING UP GELAM

Johari grew up in Gedung Kuning, the yellow mansion that was once part of the royal enclave of Istana Kampong Gelam. His great-grandfather, Haji Yusoff Mohamed Noor, bought it in 1912 and subsequent generations of his family lived there until 1999 when it was acquired by the government.

Johari remembers the arterial streets emanating from the palace as a vibrant melting pot of people and cultures that gave rise to dishes beloved today. These include mee rebus, sup tulang and mee siam.

The latter, Johari explains in the book, “underwent significant development in Kampong Gelam”, giving rise to three varieties: Mee siam berkuah (the gravied version we are most familiar with), mee siam kering (dry mee siam), and mee siam Mak Jarah (thinner strands of rice vermicelli fried in clotted coconut cream).

“Being the royal port town since 1819, (this area) was a very cosmopolitan location,” recalled the 58-year-old fondly.

“Kandahar Street was one of the most important arteries when it came to food production. Most of it was operated by Indians of different backgrounds. At the same time, we had a lot of nasi padang stalls… the famous (Warong Nasi) Pariaman and Sabar Menanti. One street down is Bussorah Street, which I would call ‘the incubator’ (because) many noteworthy recipes and new ideas were churned out here.”

The details of these foods, their creators and pioneering businesses that formed Kampong Gelam are explained in the second chapter of Johari’s book. Titled Singapore, A Nusantara Kitchen, it is part-history lesson part-personal recollection of the establishments and cultures that grew out of the enclave.

In another chapter, Johari explores the art of plating in Malay cuisine, explaining the significance of visual forms, designs and patterns. Shapes representing animal forms, for example, are reserved for special functions. Various words that describe shapes or patterns in Malay, such as keria (ring) and wajek (rhombus) are taken from dishes served in that configuration.

Throughout the book, Johari embeds themes of early Malay life, their ingenuity when it came to foraging and using food as medicine, the complexity of Malay-ness, and crucial perspectives on the traditions of Nusantara foodways that have given rise to the eclecticism of Malay food in Singapore.

Johari is a sensitive storyteller and deft historian. His clear prose and the familiar tableaus he paints make The Food Of Singapore Malays a compelling read.

Also compelling is the fact that the book is laid out such that readers can dip in without having to read it from front to back… which is itself a challenge since it measures 26cm by 29cm and weighs a whopping 3.2kg. “(I’m) not quite sure how to read it without a lectern though!” joked a mutual friend on Facebook.

TRAVELLING THROUGH TIME

Johari’s expertise is earned through years of study that has seen him travelling through Europe, Indonesia and Malaysia, visiting the likes of Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, The British Library in London for its collection of cookbooks in Jawi (Malay in Arabic script), and Leiden University in The Netherlands to speak with respected professor of Malay culture, Teuku Iskandar.

Along the way, he’s amassed a splendid collection of Southeast Asian artworks, rare books and artefacts, many of which are neatly displayed throughout his sprawling apartment in the Tanglin belt.

“There’s nothing like relying on your own materials,” Johari explained bashfully of the scores of objects and books stacked like a secondary low wall along his living room, a veritable Lego set of his life’s work.

CNA Lifestyle met up with Khir Johari, who literally wrote the book on Malay cuisine in Singapore – it’s called The Food Of Singapore Malays.

In this video, the food historian and author shares stories about growing up in Kampong Gelam’s Yellow Mansion and being immersed in the area’s rich food scene. He also gives us a crash course on the different types of Malay cuisines and… the importance of food plating.

His interest in sharing and preserving Malay culture was sparked in his university years in California. Yearning for the food of his family and reading materials in his mother tongue, Johari began delving into Malay culture and cuisine, only to find that there were few books dedicated to the subject.

More readily available were books on Southeast Asia, which he devoured, taking particular note of the information that he was really after, such as life in the Malay Archipelago, the practice of foraging and preservation techniques.

He returned home and joined the Singapore Heritage Society, where he became vice-president from 2015 to 2017. Today, he is a board member of the Asian Civilisations Museum and trains docents for the National Museum of Singapore and The Malay Heritage Centre while taking care of what he describes as a small family office.

What he thought would take about seven years to write stretched into 11. “With research, you dig up a book and you find 10 more things you need to look into. It’s hard to stop. Even as we speak, new things have surfaced since the book was published.”

There are no plans for a sequel to this monumental work, though. Now that it is out in the world, Johari says he is happy to sit back and watch its growth before thinking about what comes next.

A GEM FOR THE PEOPLE

For the Malay community, Johari’s book marks a critically clear construct of their collective history and a validating source in a time where cultural claims and appropriations are more rife than ever.

“Such a book has never been written before and its publication today is timely,” said Dr Azhar Ibrahim, a lecturer at the Department of Malay Studies in National University of Singapore (NUS).

“This book sets the information right with the backing from cultural history and the insights into the living tradition of this food culture via fieldwork contacts and observations,” Dr Azhar wrote in an email interview with CNA Lifestyle.

For non-Malay Singaporeans such as Associate Professor Darren Koh, the book is a rare glimpse into our shared culinary history and an opportunity to learn about the origins of Singapore’s first cuisine.

“What struck me most when reading the book… was how much of food we really never knew or thought about… All at once we see that the food we eat is not just ours; so much of it has been brought in from near and far. We also see how what is shared can be so different. It is truly a celebration, through the stories and the pictures, of unity in diversity,” he said.

For Johari, the 11 years of work has evolved his mission from that of documentation to one of honouring the people that comprise the history. “Over the years, it’s evolved into honouring the grandmothers and custodians of this knowledge. I want people to know why we eat what we eat… It’s important to celebrate the people before us, the generations of people who have made food the way it is today.”

He may no longer teach in a classroom, but Johari continues to educate the masses, though in a different subject altogether: His heritage. And it is information we should all lap up.