A Singaporean is the new head chef of world-famous restaurant Noma in Denmark

From choosing a different career path to making his “typical Asian” parents proud, 31-year-old Kenneth Foong is now heading up the New Nordic kitchen at the forefront of global cuisine.

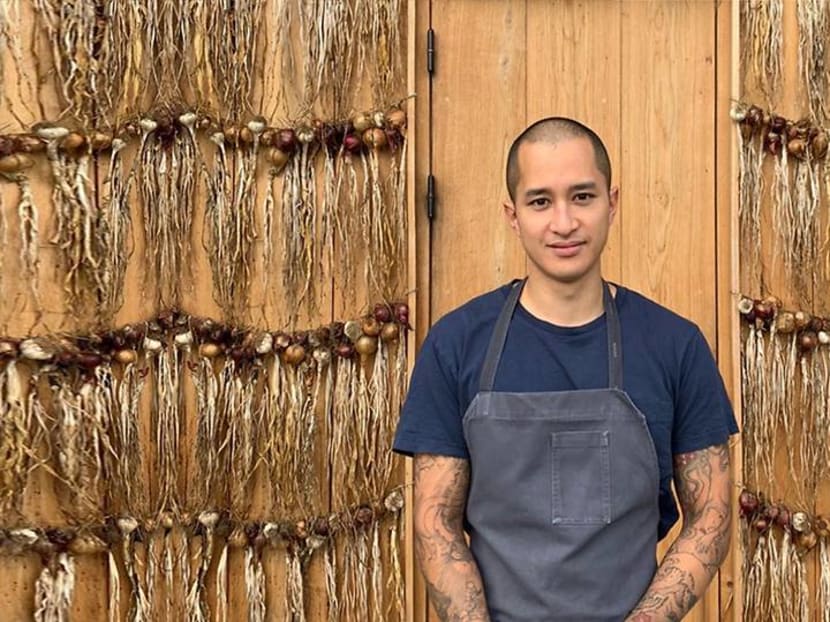

Introducing Noma's new head chef: Singaporean Kenneth Foong. (Photo: Noma)

In the kitchen and outside of it, Kenneth Foong is unflappably calm and coolly collected. So it’s perhaps appropriate that just as quietly, in July this year, the 31-year-old assumed the position of head chef in the kitchen of what must be the most talked-about restaurant in the world.

How did a Singaporean – and former Anglo-Chinese School boy, at that – come to lead the cooking team of a four-time No 1 World’s Best restaurant synonymous with "foraging", "fermentation" and "Rene Redzepi", 10,000km away in Copenhagen, Denmark?

Foong’s Noma journey started two years ago when he left his position as head chef at Cure in Singapore to stage as an intern at the restaurant on the cutting edge of New Nordic cuisine.

READ: Kitchen Stories: The personal tales behind the tattoos of Singapore chefs

Nine months later, after being conferred a full-time place, he was told that since the head chef, Canadian Benjamin Ing, would soon be leaving, there was a general consensus among the management team that he was an ideal candidate to receive the reins.

This meant that in running Noma's service kitchen, Foong would work with Jason White, director of fermentation; and Mette Soberg, head of research and development for the test kitchen, overseen by co-owner Redzepi.

READ: The Brazilian chef who embraced Singapore food thanks to a trip to Tekka market

Foong recalled being "taken aback". “It was a huge decision and, at least for me, extremely daunting to take on a role that has only been held by a handful of industry legends who have since gone forth and done amazing things in their own right,” he told CNA Lifestyle.

That said, he’s no stranger to the kitchens of the world’s top restaurants. Foong’s career began in 2010 at Restaurant Andre; he trained at New York’s Culinary Institute of America and worked at another No 1 World’s Best restaurant, Eleven Madison Park, as well as Michelin-starred Betony, before returning to Singapore in 2016 amid visa issues.

In 2018 he married his wife, who is Mexican and also a chef – the couple met while working at Eleven Madison Park – and when they moved to Copenhagen, she landed a job at Relae.

As Noma’s first Asia-born head chef, Foong appreciates how far from home he has come without feeling out of place at all.

“Growing up in Singapore, or anywhere for that matter, you would not be faulted for thinking that the best restaurants, globally, were euro-centric restaurants run by white chefs. It would have been very strange to think that an individual like myself would be able to find an opportunity like the one I am in,” he said.

“On my part, I have never felt limited because of who I am. But I guess it also does say quite a bit about the broader range of opportunities that become available to you when you choose to step out of your comfort zone,” added Foong, who has always been chiefly inspired by Asian chefs such as The French Laundry’s Corey Lee, whom he eventually got to meet when he worked for a few days at Benu in San Francisco.

READ: Everyone loves his prawn noodles, but this street food chef waits for dad’s praise

And for the food world in general, “More so than ever, the amalgamation of the global restaurant scene means that there are rarely any boundaries, literal and contextual, that cannot be permeated. You just have to comprehend the work needed to get there, set your mind to it, and take that very first step.

“It is mostly very hard work, but nothing worth doing is ever easy.”

WALKING HIS OWN ROAD

Growing up, Foong told us, he was a “problematic child” who “never really fit in”.

"In school I tried to be one of the cool kids, but I never was. I was always the strange, weird one. I was never really exceptional at sports, I was fairly decent at music – but my one refuge was cooking.”

For his “results-orientated” parents, who were “strict in the very typical Asian way”, “anything was permissible as long as I was doing well in school.”

At the same time, “they were extremely supportive of my interest in cooking. One of my earliest memories is of baking with my dad every Sunday. We would pick a recipe out of a book and go at it together. On top of that, he would take me appliance shopping fairly frequently as well, picking out a new oven or stand mixer.”

After completing National Service, “I made a very conscious decision, together with my parents, to formally pursue a career in the culinary arts. My parents raised us in a fairly hybridised home, ostensibly Asian in the best ways but with the freedoms of western doctrine. They saw the passion I had for cooking and sent me to get a formal education at the Culinary Institute of America, in New York.”

Acknowledging that he feels “extremely privileged” for the opportunities he’s had, Foong credits his parents for encouraging him to choose a career path that diverged from his peers’.

READ: Don't generalise our food as curry, says chef of 1st Michelin-starred Pakistani restaurant

“When I decided to pursue cooking professionally, there was not a lot of support from my friends or even my relatives. Understandably so – the idea of being a chef was so far from the realms of what they perceived as a viable career option. Many of them brushed it off as a phase. My parents were the first ones to stand up for me… they told me to keep at it and not listen to the naysayers.”

Moving to New York was a “life changing” decision, he said. “The metaphor of turning on a light switch would not be an exaggeration here. For the first time in my life, I felt like I did not have to conform to fit anyone’s standards or expectations. It was liberating, and with that liberation came the opportunity to push forward unhindered.”

While “Andre was the restaurant and chef that started it all for me,” Eleven Madison Park taught him that “the best restaurants have structures that are not that different from Fortune 500 companies.”

Noma is no different. “The individuals that make up the company are also a group of highly functioning individuals, many of whom cannot sit with the same routine for an extended period of time,” he said. “Noma, as an organisation and a restaurant, is constantly changing and evolving, each iteration being a more improved and, more importantly, relevant version of its previous self.”

EVERY SERVICE A “CHAMPIONSHIP GAME”

What’s it like running the kitchen of this renowned restaurant for which guests spend months on the waiting list to dine? Well, it’s not a mundane experience, to say the least.

“The intensity and energy of the place is palpable. It’s almost electric – you can feel it in the air. It scares some, but for the individuals that thrive off that energy, they just lean in and soak it all up. I am one of those,” he said.

From the first day he arrived, he noticed “people were sprinting, literally, from the start of their day up to the point they were leaving the restaurant. It was amazing. The pace of service was blistering – dishes were leaving the kitchen so quickly that diners never had the opportunity to pull out their phones or sometimes even get up for the restroom. As a professional, it is almost impossible to comprehend the operation without actually being there.”

Needless to say, leading a kitchen of that nature is anything but easy. “The stakes are just very high here, and every service is the equivalent of a championship game, in my opinion at least. The restaurant needs to be running on all cylinders constantly, and when you reach the realisation that ‘the buck stops with me', that comes with quite a bit of pressure.”

That pressure in turn leads to “a lot of sleepless nights, and anxiety in general. Personally, I started to become more aware of how stress manifests itself physically.”

He manages that through a daily routine of breathwork and meditation, bicycle riding and a strength training routine. “I find it is helpful to try to approach our profession more as athletes, as opposed to the more commonly accepted ‘rockstar’,” he commented wryly.

Foong is aware that there are dangers that come with not managing stress well.

"Unfortunately, the stigma of mental illness and fatigue is still a very real one in the industry. We tend to just brush it off. But over the years, I have seen many friends and colleagues succumb to stress in very different and very concerning ways. It is extremely debilitating and needs to be addressed more openly.”

READ: ‘This kind of place sure cannot last’: Artichoke's Bjorn Shen laughs at critics 9 years on

What has helped him, though, is having trained in the army, he said. “Being an officer in the army taught me a lot about contingencies and planning for them. It taught me to deal with uncertainty by careful calculation and planning, instead of crossing your fingers and hoping for the best.”

And “beyond that, a Singaporean upbringing instilled a sense of stoic strength, which is always useful in high-strung kitchens.”

If there’s one thing he misses about home, it’s going for a boisterous zi char meal, he shared. “I think there is something really special about the tradition of going out to have what is generally the equivalent of someone’s home cooking in a casual setting, surrounded by friends and family.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Foong’s time at Noma hasn’t been the smoothest thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the experience so far has also been fulfilling in its own way.

“Following the lockdown, we reinvented ourselves as a much more accessible burger and wine bar… We served perhaps in excess of 40,000 burgers in a span of five weeks. It was challenging, but extremely rewarding.”

As a chef, he’s also reminded of what welcoming guests to the table is all about. “If we are able to, even for just a couple of hours, create a bubble of joy, happiness and wonder that salves the anxiety of the guest and provides some semblance of normalcy, I would consider that a job well done.”

Foong’s journey of personal development continues, too. “I always had a very paralysing fear of stagnation. It informs a lot of my personal goal settings and ambitions. I am also extremely competitive by nature,” he confided.

“But my pursuit of excellence has shifted from the accumulation of world-class restaurants under my belt to just constantly striving to become a better individual, both professionally and personally. As a chef, I am convinced that they are one and the same.”

READ: Adventures in DIY fermentation: From onion-chilli paste to grasshopper garum

If he had to think about what the next step beyond Noma might be, he said, he would like to travel around Asia, especially within China, and take a deep dive into the food and culture. “I would like to learn to cook the way my ancestors did, and get an understanding of how culture in general shaped the way they think about food and cuisine.”

For now, while he runs one of the most-watched kitchens in the world, it’s enough to know that his parents back in Singapore are proud of him “in their own way”.

“It continues to be difficult for them to understand how this stacks up in the non-food world,” he mused. “They do not necessarily comprehend the significance of Noma or what it has done – but I consider that to be really special. For your parents to be unconditionally proud of you despite not having a full grasp of what you do – it is rather poetic.”