Death and my mother’s conversations: Great loss becomes part of your story

My Singapore Life is a CNA Lifestyle series about coming of age in the Lion City. And there is no real coming of age until one has come face to face with the unbearable.

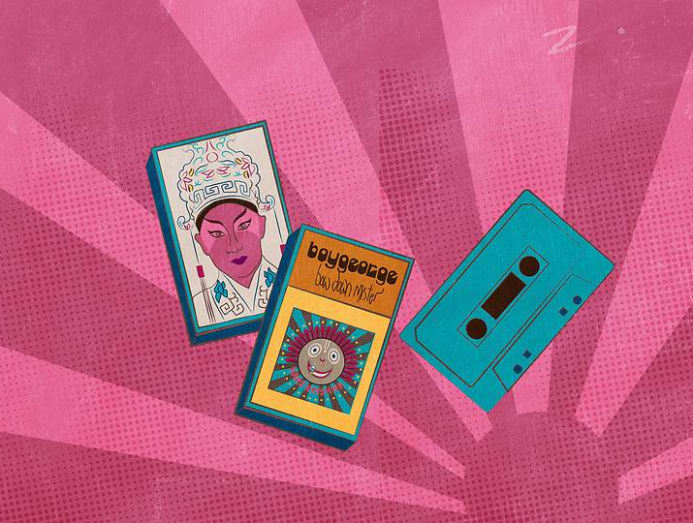

(Illustration: Chern Ling)

In 1989, I was attached to a public relations company as part of an internship programme. I remember printing flyers during lunch, using the fancy office laser printer. At that time, mere mortals only used what was referred to as a dot matrix printer. The noise would make a cat jump, but it did its job.

I was also introduced to computers around then, spending endless hours at the computer lab of the Faculty Of Arts And Social Sciences in NUS (National University Of Singapore), typing out essays for courses which no longer accepted hand-written submissions.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: Death And Loss, And My Mother’s Conversations, read by Lim Yu-Beng

Death, loss and my mother’s conversations

These transitions served me well. I had just started writing plays and thankfully, didn't have to do it on a typewriter.

You are a jack of all trades. When are you going to do one thing, and do it well?

Till then, writing had always been a form of escape. I loved dreaming up stories for my “composition” class in school, and getting lost in story books. I didn't read novels till ... well, till I had to.

School and college days were all about my desire to “express yourself”: Drama club, school magazine, debating team, band and student council. I even studied French for two years.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: The Girl Who Hung Out With The ‘Mat Roker’ Boys, read by Pam Oei

My mother eventually said one day: “You are a jack of all trades. When are you going to do one thing, and do it well?”

It was meant to be a dig at my “express yourself” approach to life. Why not settle down with one? One subject. One interest. Medicine, perhaps. Or Law, if I was so inclined.

READ: Life In 90s Singapore: The haunting of Ginza Plaza

But who cares about medicine, or law, when you’re in school? It was all about the music. My friends and I were too busy sharing mix-tapes of British synth pop bands. I was the uncool one who didn't know about REM, ABC and OMD. I graduated from the school of ABBA and Boney M, so I had some catching up to do.

Even in our own SING-POP backyard, we found influences and influencers. We wanted to be in Dick Lee's music videos with his trendsetter friends. Life In The Lion City! Internationaland! Hanis! Ja! Hemispheres! Ethel Fong! Nora Ariffin!

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: The Rise And Fall Of Being AWOL: A Band’s Rock Star Dreams In Singapore, read by Lim Yu-beng

I bought a marked-down, two-toned Bobby Chng shirt. I even owned a pair of zouave pants. Although there is no physical evidence now that I ever did.

And then, surreptitiously, Chris Ho and Zircon Lounge introduced me to French writer Jean Genet. Fast forward to the National Library – or was it the British Council Library at Shenton Way? – with a copy of The Thief's Journal in my hands. And because the god of cinema loved me and my friends, we were bestowed with a VHS copy of Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Querelle through someone's beatnik sibling.

At home, there was none of that. This secret life was not to be confused with real life. In the nightly family TV ritual, we watched sitcoms and detective shows. No spoilers, but wherever Angela Lansbury goes, someone's sure to die.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: The Haunting Of Ginza Plaza: A Childhood 'Pen Fairy' Game Goes Terrifyingly Wrong, read by Pam Oei

By the time my mother slotted in her favourite Mahabharata video into the VCR, it was time to say goodnight.

READ: Life In 90s Singapore: Blood and innocence on the school bus

These were the formative years. On the cusp of 1990. Whenever I tried a new hobby or pursued a new interest, my mother would say again: You are a jack of all trades.

And then, theatre came knocking. And playwriting basically kicked the door down. Take that, Jack!

By the time I was nonchalantly printing theatre flyers on the laser printer at my internship office for my play Lanterns Never Go Out; or writing serial numbers on stacks of green, pink and blue perforated tickets for This Chord & Others; or being slapped by a fellow actor on stage until my ear drums burst in Still Building; or visiting Woodbridge Hospital and halfway houses, speaking to psychiatrists, social workers, patients, ex-patients and counsellors for Off Centre, I knew two things.

One: I was prepared to not live “the glamorous life”. Two: I was no longer a Jack, and I was on my way to – hopefully – being a Master Of One.

READ: Life In 90s Singapore: Buying acceptance at the temple of cool

When I wrote my first few plays, the dialogue flowed so smoothly, it didn't feel – almost didn't feel – like I was writing. My years of listening to my mother speaking to her friends on the phone had paid off.

I found in playwriting a way to create, to write, to imagine. I found a way to make people say things they meant – or didn't; for people to argue, because they cared; to bring attention to situations and issues in society.

Thank you, Jimmy Somerville and Alison Moyet. And Chris Ho.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: My Dial-up Modem And The White Noise Of Falling In Love, read by Pam Oei

Pop culture helped. It still does. All those hours of watching Mind Your Language didn't go to waste. I continued buying CDs of film soundtracks and favourite artistes. In my play Hope, I used Go West by Pet Shop Boys. In Off Centre, Bow Down Mister by Boy George.

Playwriting also brought me to the world. I went to Australia for a conference, the United States on a fellowship programme. I spent a year in the UK and earned my post-graduate degree.

Most importantly, playwriting brought me home. I found my calling – my true faith – and an excuse to continue eavesdropping on my mother's conversations.

But cue the soundtrack of Edward Scissorhands. A bildungsroman doesn't just end with discovery and growth. Or adulthood. There's no real coming of age until one has come face to face with death and loss.

And in 1997, I experienced the greatest loss.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: Buying Acceptance At The Temple Of Cool, read by Pam Oei

Part of the reading staple of my childhood comprised the Amar Chitra Katha comic books. Stories of Hindu deities and Indian mythology. The books and stories were colourful and absorbing – although I was never able to tell if they were real or mythical. Maybe that wasn't the point.

Besides the chronicles of heroes and, very rarely, heroines, I also read about Dharma, the rules of life, and one's stages of life.

The Brahmacharya is the “student” stage of a person's life. The second stage is Grihastha or household life – the life of a married man. The third stage is Vanaprastha or retired life. And the final stage, Sannyasa, or renounced life.

At 53, I have still not reached Stage 2. I am still a Brahmacharya, a kid, until I transition to retired life – and eventually renunciation.

Growing up in Singapore, with relatives in India, death was often a distant affair. Grief was muted, brief, unspoken of to friends and neighbours.

These “Sunday School” lessons never meant much to someone with a dual identity, common with many children of first generation immigrants. That fracture between home life and school or friend life. That sense of attachment and detachment, of home and country, ethnicity and nationality. Of “official” and “others”.

Growing up in Singapore, with relatives in India, death was often a distant affair. Grief was muted, brief, unspoken of to friends and neighbours. Besides a few middle-of-the-night phone calls, my mother's white garb and vegetarian food at home – “outside you can eat anything” – life went on as per schedule.

When I started writing plays, consciously or subconsciously, I tried to capture these complexities. The multiple identities within an individual can be liberating or it can be enslaving. Playwriting, I tell those I teach, is the best way to write about yourself. You can transfer whatever you want from your real life to your play, and no one will know. Because you are not “present” – only your characters are.

LISTEN: My Singapore Life: Blood And Innocence On The School Bus, read by Lim Yu-beng

If someone asks, just say: “It's not me – it's the character”. You can write about your lived experience, your friends (or frenemies], your family.

You can write about your mother.

READ: Life In 90s Singapore: The rise and fall of being AWOL

I read somewhere, that when you experience a loss, the pain will never go away. It will never get smaller. But, your life gets bigger. You get older.

What happens when that, which is unbearable, becomes a part of your life journey? Your favourite times can be your most painful. Receiving an award and mourning a loss. Celebrating a milestone and feeling utterly desolate.

Your life gets bigger. You get older. You skip from one stage of life to the next.

Your life gets bigger. You get older. The shield you have formed begins to soften.

Your life gets bigger. You get older. You remember less.

The friends from school.

The songs. The bands. The fashion. The movies.

Querelle. My Own Private Idaho. It's My Party.

The walks along East Coast Beach.

The laughter of Mind Your Language.

The sound effects of the Mahabharata.

Listening to her phone calls.

The irreversible is both tragic and assuring.

I read somewhere, that when you experience a loss, the pain will never go away. It will never get smaller. But, your life gets bigger. You get older.

In my play godeatgod, a wife awaits the fate of her terminally ill husband. At the end of the play, she says:

He left on a Sunday evening … It was cold because it had been raining. I sat by his side for an hour and watched him. I could only look at the numbers on the machines … Going lower and lower and lower …

The nurses came in and drew the curtains. They started switching off all the machines. With their gloves on, they removed the tubes from his nose. They pulled out the needles from his arm, his wrist and his throat. I packed his bags as they changed him. They asked if I wanted to bring the flowers and gifts home. I said no. They started pushing the machines away, then a trolley with the tubes and the needles, then another trolley with the flowers and the gifts.

I took his bags and went outside. I signed the death certificate, collected his IC and Medisave forms. I went back in. The curtains were open. And he was no longer there. He was no longer there.

She was no longer there.

Haresh Sharma is the resident playwright of The Necessary Stage. New episodes of My Singapore Life are published every Sunday at cna.asia/podcasts.