IN FOCUS: How urbanised Singapore is learning to live with its wildlife

After the announcement this week of plans to create a new nature park network in the northern part of Singapore, CNA looks at the country's changing relationship with its natural environment and the efforts to ensure it can flourish while urban development continues.

A hornbill in flight in Singapore. (Photo: Bernard Seah)

SINGAPORE: On the way to dinner one Sunday evening, this journalist spotted five hornbills flitting across a road junction to rest in some trees - as much a part of the city landscape as the Velocity@Novena Square mall behind them and the lanes of traffic below.

In the housing estate just across from the mall, oriental pied hornbills preening their black-and-white plumage and chomping on fruit with their curved bills are a regular sight. The large bird with a distinctive casque on its beak is hard to miss but for nearly a century, they were a rare sight in Singapore.

They vanished from Singapore in the late 19th century and the first recorded return of wild oriental pied hornbills was on Pulau Ubin in 1994. Dr Ho Hua Chew, a long-time conservationist, was among the Nature Society Singapore (NSS) members who spotted the birds back then.

"The bird is a spectacular species and being regarded as extinct in Singapore up to that date, it was a thrilling experience to see a comeback for such large forest species – especially two birds at that," he said.

Dr Ho said the hornbill sighting instilled hope in him for nature conservation in Singapore, which for decades was "all gloom and doom" with the country's nonstop construction and development.

But following a conservation project to bring back the birds, hornbill sightings have become far more common.

By installing nest boxes in trees for the birds to breed in, the Singapore Hornbill Project’s collaborators, who include the National Parks Board (NParks), Wildlife Reserves Singapore (WRS) and researchers, got visiting birds from neighbouring countries to settle here and raise their babies.

The hornbills are an eye-catching example of the many projects in Singapore aiming to preserve what is left of its biodiversity in an urbanised landscape - a movement that has grown gradually over the last couple of decades.

These include not just species recovery initiatives, but also efforts to restore habitats and connect them through nature ways - routes planted with specific trees and shrubs to facilitate the movement of animals. Many of these projects are part of Singapore's continually updated green master plans.

Dr Yong Ding Li, ornithologist and scientific adviser for the Nature Society's bird group, estimates that the population of oriental pied hornbills here has been expanding steadily in the last two decades and now number in the “low hundreds”.

The birds, which live on the forest fringes, have established themselves sufficiently and there is now no need to intervene, according to Mr Lim Liang Jim, group director of NParks' National Biodiversity Centre. NParks’ greening efforts have contributed to this, as there are now enough mature trees for birds which nest in tree holes - like the hornbills and parrots - to breed in.

Dr Yong added: “I think there's a role that greening has played in allowing hornbills to recolonise the main island. Now the interesting thing is that on mainland Singapore, the hornbills are largely not in our central nature reserves.”

OTTERS RETURN

The return of such wildlife is a side effect of policies that can be traced back to founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s vision to green Singapore and clean up its waterways - efforts which were meant to improve the welfare of the island’s human inhabitants and to enhance Singapore's reputation abroad.

Environmental activist and National University of Singapore biology lecturer N Sivasothi said that the city’s smooth-coated otters found that Singapore’s clean waterways, some of which have been naturalised, also suited them.

“So the river cleanup was not about supporting wildlife, it was about providing clean water for people,” he said. “Although otters were missing in Singapore for a few decades, as we cleaned up for people … suddenly they were seen.”

But not every species can thrive in an environment built for people, and as Singapore continues to develop, will there be room for wildlife?

For instance, the urbanised smooth-coated otters’ prominence is in contrast to the fate of its rural cousin, the small-clawed otter.

“(The small-clawed otter is) a small mangrove stream-dwelling kind of animal. The modified environment it can deal with is maybe padi fields, but it can’t deal with modified urban environments, so its fate is hanging in balance in (Pulau) Ubin and Tekong,” said Mr Sivasothi.

Much of Singapore’s wildlife are hidden in the pockets of forest that remain in the heart of Singapore, and some, like small-clawed otters, persist on the north-east islands.

“What happens is the urban adapted species are prominent but the ones that cannot hack it, you don't see,” said Mr Sivasothi.

“If you talk about wildlife conservation, ultimately what must you do is conserve habitat. We should invest a lot of effort into restoring, recovery and then connecting (them).”

READ: Sungei Buloh Nature Park Network to be established, includes new Lim Chu Kang Nature Park

READ: Singapore to plant 1 million trees, develop more gardens and parks by 2030

That effort to conserve, restore and connect natural habitats is a major part of the City in Nature vision, announced by National Development Minister Desmond Lee in March.

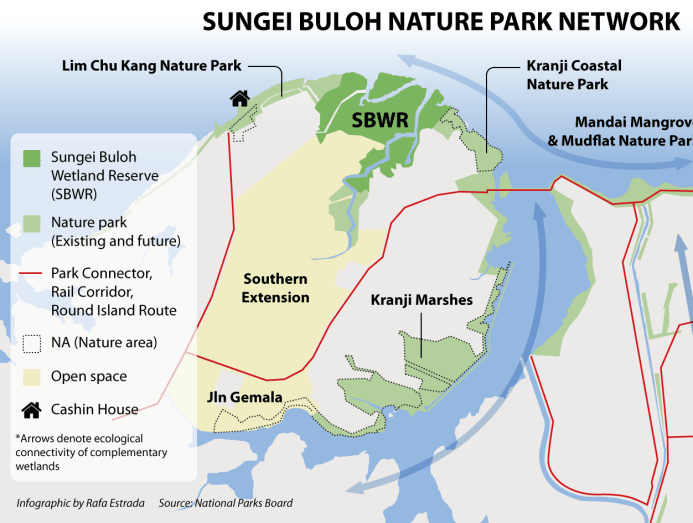

On Wednesday, NParks announced new plans to create a 400ha nature park network that will envelop the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, the Kranji Marshes and other nature areas - in another step to protect Singapore’s four nature reserves.

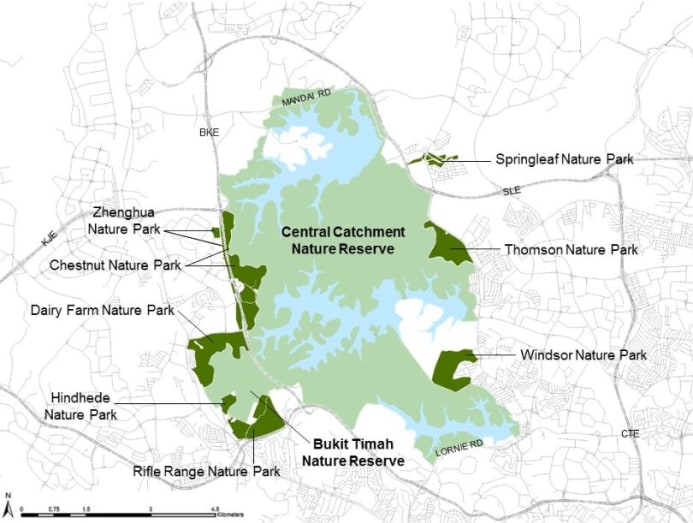

A network of buffer parks has already been added to Singapore’s Central Catchment and Bukit Timah Nature Reserves. These buffers protect the central nature reserves from developments that abut them and give the public alternative green spaces to visit so as to ease pressure on the reserves.

The development plans for Sungei Buloh take into account its role as a key node for migratory waterbirds along a flyway that stretches from the arctic to New Zealand - a science-based and ecologically friendly approach that is increasingly evident as Singapore tries to protect what is left of its natural heritage.

“IF YOU LOSE THEM HERE, YOU LOSE THE WHOLE WORLD'S POPULATION”

As the sky lightened and the forest awakened, bird calls and macaques’ chatter punctuated the keening of cicadas at the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve. In ever-changing Singapore, this patch of primary rainforest is a reminder of what much of the island looked and sounded like 200 years ago.

On any given day, the nature reserve is filled with hikers and panting joggers labouring up and down its slopes, but few see most of the flora and fauna that call it home.

One of them - the Johora Singaporensis, freshwater crabs found only in Singapore - infamously made it onto a list of the 100 most endangered species in the world. Its tiny population of a few hundred is found in fast-flowing streams on hills, of which there are only a handful here.

The Singapore freshwater crab has already vanished from a hill stream in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve where it was first discovered in the 1980s, a turn of events that sounded the alarm for researchers years back.

“They're unique to Singapore. That means, if you lose them here, you lose the whole world's population,” said Associate Professor Darren Yeo, a freshwater ecology expert at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) department of biological sciences.

READ: Babies of critically endangered Singapore Freshwater Crab hatched in captivity

A concerted effort to save the pebble-sized invertebrate was mounted in 2015 by NParks, WRS and NUS, leading to more than 100 crabs being released in the wild. The crab population has likely increased in recent years due to successful breeding programmes and translocations, said NParks.

But the fate of the species remains precarious because its habitats are so limited. Research on its ecology is now ongoing to investigate possible threats to the species in the wild, such as stream acidification and drought, possibly due to climate change, said Assoc Prof Yeo.

The crab, described by Assoc Prof Yeo as a “little brown thing” more comfortable scuttling under rocks than being the centre of the media spotlight, is one of the lucky ones.

“A HERCULEAN EFFORT”

A 2003 study found that Singapore had already lost about 28 per cent, or 881 of 3,196 recorded species, in 200 years without much fanfare. The main reason was habitat loss, after more than 95 per cent of the island’s forest cover was lost to agriculture and later, urban development.

As many species here could have been lost before ever being documented, by referencing species found in Malaysia, the study’s authors inferred that the true extinction rate could have been as high as 73 per cent.

The study also estimated that forest reserves covering only 0.25 per cent of Singapore’s area hold more than 50 per cent of the native biodiversity left.

READ: 40 species potentially new to Singapore discovered in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve survey

READ: 150 hatchlings born last year at Singapore's only turtle hatchery: NParks

But efforts to conserve Singapore’s biodiversity has come some way since, and hundreds of plants and animals have been discovered or rediscovered here since 2013, as surveys of wildlife proliferated.

“It's really a Herculean effort to bring all this back ... Before we know what to bring back, we realised that we had to first find out what's there," said NParks' Mr Lim, Over the last seven years, surveys have discovered or rediscovered more than 500 new species, he said.

Numerous projects to conserve key species, including the Singapore freshwater crab, sea turtles and indigenous plants like the Singapore ginger, were also started over the years.

Then, the 2003 study’s authors called some surviving species the “living dead” - including the white-bellied woodpecker, the cream-coloured giant squirrel and the banded leaf monkey - as their numbers were deemed too small to be viable in the long term.

READ: 'Can't wait until it's too late': Wildlife Reserves Singapore ramps up breeding efforts for endangered species

The cream-coloured giant squirrel has not been sighted here since 1995, and Dr Yong told CNA that he last saw the white-bellied woodpecker - Singapore’s largest woodpecker - in 2001. The presence of the white-bellied woodpecker and a diverse woodpecker community are indications of forest health, as they need good forests with tall trees to survive, he added.

“The majority of forest animals will be in decline just because the forests are too small, but we can help by trying to create corridors to connect the different forest fragments.”

He calls the Eco-Link - a highway for animals built in 2013 - one of the most important conservation actions that Singapore has ever taken, as it connects the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, which were bifurcated by the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE) in 1986.

WHEN WILL THEY REACH THE “TIPPING POINT”?

Despite the challenges, primatologist Andie Ang is trying to bring the banded leaf monkey, also known as the Raffles' banded langur, back from the brink of extinction.

Up until the 1920s, the langur was found in many parts of Singapore, including Tuas, Bukit Timah and Changi, before development claimed most of its habitats. Unlike the more common long-tailed macaque, the shy creatures have found it hard to adapt to a Singapore with little forest cover.

The last banded leaf monkey in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve was believed to have been mauled to death by a pack of dogs in 1987, leaving the Central Catchment Nature Reserve as the last stronghold for the primates. Studies on them were few and far between but in 2008, a survey found about 40 langurs left here.

Twelve years on, Dr Ang, who leads research and conservation efforts for the banded leaf monkeys, estimates that their numbers have increased to more than 60 in Singapore.

With the slight increase in population, a group of bachelor monkeys tried to make their way back to Bukit Timah a few years back but one died in a road accident on BKE. While other animals have used the Eco-Link that now connects the two forested areas, the monkeys have yet to figure this out, said Dr Ang, a research scientist at the WRS Conservation Fund.

“They're always facing pressure in terms of where they can go and where they can remain,” she added.

Given their small numbers, just one catastrophic incident, such as a heavy storm or a fire, can eliminate all the langurs. A disease or inbreeding may also wipe out the population, which DNA analysis has shown to have low genetic variability.

"With an inbred population, it takes time for signs to show and it also takes time before the population would crash suddenly, so I'm just afraid when they are reaching that tipping point,” said Dr Ang.

The bachelor group of monkeys has settled in Windsor Nature Park, one of the buffer parks created on the edges of the nature reserves to protect the core areas from further disturbance.

READ: NParks unveils 10-year action plan to make Singapore's rainforests more resilient

READ: Three coastal areas proposed for conservation in Singapore Blue Plan

But Dr Ang fears that they will be affected by works for the upcoming Cross Island Line, which would lead to the clearing of a part of their habitat which is not protected as it is outside the nature reserve.

Discussions with the Land Transport Authority (LTA) are ongoing to safeguard the flora and fauna in the area when construction of the line begins, the authority said.

SMALL FORESTS, HIGH STAKES

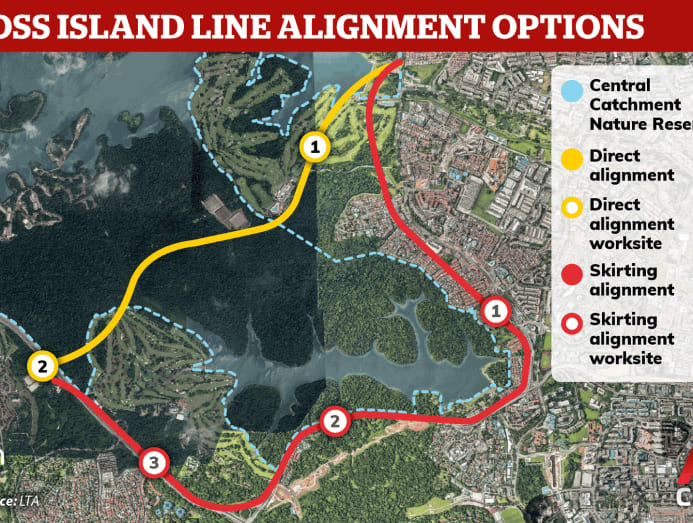

That discussion is a continuation of an engagement process that has been going on since 2013 when plans for the MRT line - which could have gone under or around the Central Catchment Nature Reserve - were first announced.

Said Mr Sivasothi, who has been actively involved in the engagement: “Our local species are all locked up in the nature reserves, which is why we are so energetic when it comes to engagement because you make one slip-up - the damage, the impact is extremely high.”

Highlighting the fragility of the nature reserve, Mr Sivasothi said that when environmental impact studies were being conducted, the companies employed were not used to the small size of Singapore’s forests and the minor disturbances that could tip the balance.

“The scale at which we are telling them they have to take into account - they've never really faced before - it's like a macro-scale to a nano-scale,” he said.

After years of debate and consultation, it was announced in December 2019 that the line will tunnel under the nature reserve but go 70m deep, instead of the usual 20 to 30m. There will be no surface work sites in the nature reserve to ensure that flora and fauna will not be affected.

READ: Cross Island Line to take direct route under Central Catchment Nature Reserve

READ: Six years in the making - how the Cross Island Line's direct route was decided

While not everyone was satisfied with the final decision, there was a definite desire for a constructive outcome and a “willingness to listen”, said Mr Sivasothi.

Nature Society president Shawn Lum credits the LTA for committing to a long engagement with nature groups early on and being open to trying new technology to get the MRT line built while reducing the impact on the nature reserve.

“They, of course, had certain constraints on how that line could be built, but the fact is that, really, through the engagement LTA … changed the way they did much of their work and so the nature reserve was able to escape from the worst kind of impact,” he said.

It is a stark example of how Singapore’s conservation plans have to face the concrete reality of its limited space, the need to accommodate more than 5 million people and the relentless race for economic growth. The process also highlights the tussle between conservation and urban development that has played out over the years in the give-and-take between authorities and environmental activists.

FROM CONSERVATION TUSSLES TO ACTIVE ENGAGEMENT

The kernel of the Sungei Buloh Nature Park Network started in 1989, when a group of birdwatchers and nature lovers successfully lobbied the Government to set it aside as a nature park. It was the first time Singapore had set aside land for nature conservation since its independence - but it was the exception rather than the norm for many years to come.

Dr Ho, who has been involved in conservation work since the mid-80s, was among those who helped save Sungei Buloh. He recalls how a petition with 25,000 signatures a few years later in the early 1990s could not budge the authorities’ resolve to build Housing Board flats in Sembawang over the Senoko Wetlands - then home to endangered resident and migratory birds.

But despite such setbacks, continued pressure from nature activists convinced the authorities to take them seriously, even as popular support for nature and cultural heritage conservation grew over the years, Dr Ho said.

READ: Bill to amend Wild Animals and Birds Act introduced in Parliament

READ: Strong support for tougher wildlife protection laws in Singapore: Survey

There were two big conservation tussles which he believes helped to turn the course of the engagement process with the authorities - the Chek Jawa wetlands on Pulau Ubin and the Bukit Brown cemetery.

“What followed from these two fierce/heated tussles was that the authorities became more friendly and willing more to listen and understand our positions,” he said in an email.

Dr Lum said that there has been a more systematic effort to include feedback from various communities, including the nature groups, on major infrastructural projects in the last decade or so. While there was always a pipeline for feedback, it used to be more informal.

Besides the Cross Island Line, he cites the development of the Rail Corridor as an example of how the Urban Redevelopment Authority took on the community as a partner in developing plans for railway land that was returned to Singapore in 2011.

Dr Lum believes that with more people with different backgrounds and expertise involved in the planning and urban development process, better outcomes can be reached.

“I think if you took all these great ideas, and these technically skilled people who have know-how in whatever - engineering and building, modelling and nature - we might be able to do something that no one agency or no one institution or individual could have thought possible,” he said.

“But in order to tap into that expertise, the discussions have to start really early and not necessarily unveiled as this plan that just needs a fine touch at the end.”

EVOLUTION, NOT REVOLUTION

Mr Lim of NParks’ National Biodiversity Centre said that the change in approach over the years has been organic.

“It was very evolutionary, it wasn't revolutionary. But essentially, there was a recognition, I think for quite some time already ... that the community has to be involved,” he said.

It is not just the approach to engagement, the evolution in Singapore’s relationship with the natural environment can be summed up in its slogans over the years - from “Garden City” to “City in a Garden” to now, a “City in Nature”.

Explaining the significance of this, Mr Lim said: “We are now looking at nature as really being part of a very critical relationship with people ... simply because we recognise now that nature - flora, fauna, habitats and ecosystems - play an important role (in) imparting resilience to the community, to human individuals, to society, to nations.”

There is now an understanding that having more natural ecosystems, rather than controlled green spaces is important for ecological and climate resilience, said Mr Lim. There is even scientific evidence that being in a more biodiverse environment improves mental well-being, he added.

Of the seven strategic thrusts of the City in Nature vision, conserving and restoring natural ecosystems is the first. Other key thrusts include restoring nature into the built environment and establishing connectivity between green spaces islandwide - for humans and for wildlife.

It has come a long way from 1967 when then-PM Lee Kuan Yew announced that Singapore was to become a “garden city beautiful with flowers and trees, and as tidy and litterless as can be”, as reported in the Straits Times.

Getting the community engaged, in particular young people, is another key thrust. Mr Lim said he is seeing more interest in nature conservation, and many people, young and old, committing their time and expertise to NParks’ community programmes.

“IT ALL BEGINS WITH UNDERSTANDING THE NATURAL WORLD”

At Commonwealth Secondary School, students have been learning in an environment which is a microcosm of Singapore’s natural habitats - from a rainforest to a wetland, and a freshwater stream. It is one of 42 schools in NParks’ Greening Schools for Biodiversity Programme, which helps schools plant native flora and create habitats for more wildlife.

The animals that stop by the school became learning opportunities, such as when a reticulated python was found in a school corridor or when a pair of olive-backed sunbirds built a nest there this year.

Mr Jacob Tan, biology teacher and key driver of the school’s environmental education programme, said that the school’s geography teachers have also been using the eco-habitats to get students to link what they observe to their lessons.

“This is the generation of students who will inherit a world where these issues are really going to be a problem. As our students live in an urban environment, the opportunity that they have to get in contact with nature and biodiversity in general is very little,” he said.

One young person whose love for nature has turned into both a job and a sideline is 26-year-old Kong Man Jing, a science teacher at a tuition centre who also runs Facebook page Just Keep Thinking, dedicated to educating people about science and the environment and has more than 63,000 followers.

Ms Kong’s alter-ego “BioGirlMJ” is the bubbly host of science and nature videos that feel like a blend of Discovery Channel and SGAG. During the “circuit breaker” period, she went on a “grassland treasure hunt”, identifying for viewers the flowers, weeds and insects that proliferated when the grass went untrimmed for months.

Ms Kong told CNA that she wants her videos to fill a gap for light-hearted content on such matters that are accessible to the masses - particularly the unconverted, who may not be that interested in green issues.

“It’d be great if everyone cares about the environment a bit more because climate change is real, but to reach there, I think it has to come from innate desire,” she said. “When you love something, you want to protect it more.”

SINGAPORE A “CRUCIBLE” FOR THE WORLD?

Most people CNA spoke to said that the issue is larger than Singapore and saving its native wildlife.

Ornithologist Dr Yong pointed out that Singapore’s ecosystem merges into Malaysia’s and Indonesia’s, and international ecological connectivity is often overlooked.

“If you look at the Johor Straits ... we cannot see the Singapore side as a ‘Singaporean ecosystem’, there's no such thing as a Singaporean ecosystem. To animals, to plants, the border is an artificial thing,” he said, urging for more transboundary cooperation on nature conservation.

NParks' Mr Lim said that Singapore can be a “test case” for other cities in the world.

"Singapore is very interesting because it is a crucible … a test case of how basically a small nation with very small hinterland - in fact zero hinterland, let’s be honest - will be able to build a matrix of greenery, of nature so that it benefits people as much as possible,” he said.

Dr Lum of the Nature Society said that he feels it is time the world draws a line on urban sprawl if it wants to enjoy the services that nature provides, like climate regulation, clean water and air.

“I think all countries in the future would have to kind of draw a boundary: Beyond this, we just cannot develop, we have to put everything in this ... And so in this sense, Singapore really becomes a test case for how creative can we be in our allocation of land.”