Making the journey back to the little village where my family’s story began

Welcome to Red Stone Village, Guangxi, China, where one Singaporean discovers how little of her own history she knows – with relatives she never knew she had.

Children join the writer for a sumptuous meal of fish, chicken, pork belly and vegetables. (Photo: Hon Jing Yi)

I woke up on a bus in rural Guangxi, China, and found myself looking at cows and calves standing in the fields, my eyes squinting as they adjusted to the sunlight.

Without access to data or Wi-Fi, I estimated I was still two hours away from my destination. While most visitors aim for picturesque Guilin, in the northeastern part of China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, I was headed southeast, to a tiny village in Rong County – where the story of my family began.

Perhaps like most Singaporean children, I had never been curious about “my roots” growing up. I knew that my paternal grandfather had migrated from Guangxi to Kota Tinggi in Malaysia in search of a better life, the same way my father later moved from Kota Tinggi to Singapore.

My grandfather, who passed away before I was born, was but a nebulous figure in my head, pieced tenuously together with the few stories my father had told me about him and the photo on his headstone I had come to know so well over two dozen Qing Ming Festivals and visits to his grave in his adopted home.

But when my work called for a trip to Nanning in Guangxi, I leapt at the opportunity to take a day trip to this village my father had always spoken of. I was largely curious about the place that had birthed and sheltered generations of “Pan”s – my Chinese family name.

My journey had a rocky start. As it were, no one really knew where the village was, and what it was really called. My father, who had never been to Guangxi himself, had told me all my life that his father had lived in a small village called Yang Shuo. After some Googling, it became abundantly clear that it was not the case, as Yang Shuo was a relatively prosperous city.

Through my uncle – my father’s brother – I got in touch with another uncle – my father’s cousin – who lived in Shenzhen. That uncle put me in touch with his younger brother, who still lived in the village and who agreed to show me around.

Then came the actual visit. My journey began almost at the crack of dawn, with a two-hour wait at the cockroach-infested Langdong Bus Station in Nanning. I jostled with men who stuck their heads repeatedly in front of me to buy bus tickets at the counter, never mind that I was standing in a queue meant only for ladies.

The bus ride, though long, was surprisingly comfortable. A bus attendant wearing a bright red sash handed out bottles of water, after barking at everyone to put their seat belts on, and the rocking motions of the bus soon put me to sleep.

THE WOMAN WITH THE FISH BONES

After nearly four hours, we pulled up in a dusty town. I stepped out of the bus station, trying to ignore the little boy peeing at a tree in my line of sight, looking for signs of my chaperone. Then, a couple who looked to be in their late 40s walked towards me. Tan and slender, the man looked nothing like me, or anyone related to me. But I knew from their smiles – as well as a brief exchange over text before I’d arrived – that they were my uncle and aunt.

Over the drive to the village, they asked how long the flight from Singapore was, and if it had been my first time on a plane. I found out that my uncle worked in a company that sold farming equipment while his wife, a humble, wonderfully pleasant woman, worked in the fields. At least, that is what I gathered, as they spoke only a smattering of Mandarin, and the Guangxi dialect they spoke sounded nothing like the dialect I’m used to hearing my father speak.

An hour later, we finally arrived at Red Stone Village. There was a surprising amount of concrete – sparse, grey structures of all shapes and sizes that looked like they housed everything from chickens to humans.

My uncle and aunt took me to the ancestral shrine, which dates back about 250 years to the Qing Dynasty. I spent about 10 minutes looking around the spacious hall, inspecting the names on the tablets of my ancestors, wondering about the stories from my own history that I will never know.

We walked to a two-storey compound, where my uncle and his extended family lived. By now, about a dozen villagers – many of whom were apparently my relatives – had gathered around to see who their visitor was, including an elderly man who was very excited to meet a long-lost Pan. Two young boys, wearing mud-stained clothes and toothy grins, came up for a closer look at my camera.

We all sat down for a late lunch on stools at a large wooden table in the middle of the courtyard, as dogs, cats, chickens and ducks walked freely around us. My generous hosts had certainly gone out of their way to welcome their random Singaporean niece, and I felt slightly guilty that my visit was inconveniencing so many.

There was a heap of steaming white rice, platters of delicious steamed fish, vegetable, chicken, and a particularly large serving of my father’s favourite dish, steamed pork with preserved mustard – curiously not unlike the dishes my family stills eats at Chinese New Year.

I attempted to chat with a friendly, rotund woman with a ruddy complexion who sat next to me and fed herself while rocking a baby to sleep. We didn’t really know what to say to each other, or how to communicate. After I recovered from the shock of watching her spit fish bones directly onto the ground – though they were swiftly consumed by a quick-thinking cat – we decided to simply beam each other and do what us Chinese people do best – pile more food into each other’s bowls.

MEETING MY GRANDFATHER

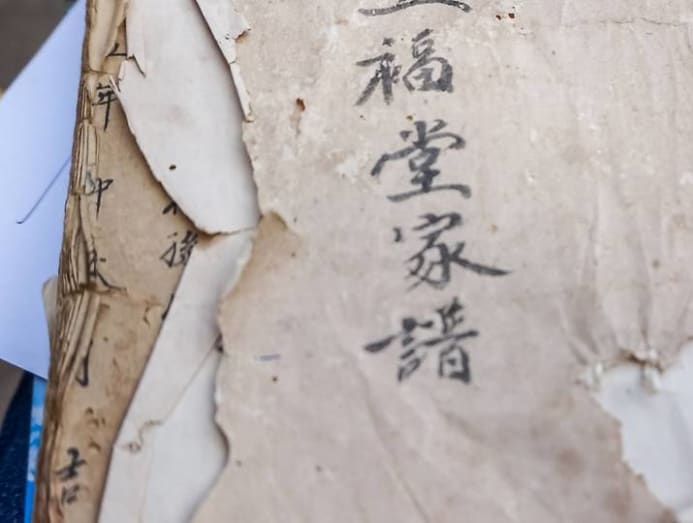

After lunch, my uncle sat me down, holding in his hands a book so old, the pages were brown and falling apart. It was our family’s genealogical register, a meticulous record of generations and generations of Pans – though, unfortunately, only the names of men were recorded. Some of the entries even contained information about their greatest achievements and current whereabouts.

My uncle flipped to the last few pages and pointed to my grandfather’s name – Pan Qing Guo. He told me how he had ended up in Malaysia, a story even my father didn’t know.

My grandfather had four older brothers, and an unknown number of sisters. The eldest had remained in China to take care of the family, while the rest sailed to Malaysia and Indonesia to work. Two of these brothers, including my uncle’s father, eventually went back to the village. But then the civil war broke out, he said, and the other two brothers, including my grandfather, were left stranded in Southeast Asia.

That was all the history my uncle was able to tell me about my grandfather, but I was familiar with the story that followed. He eventually settled down in Malaysia and began life with my grandmother after an arranged marriage. My grandfather spent most of his working life as a cook for lumberjacks in a plantation in Indonesia, saving up money, returning only for a few weeks every year to Kota Tinggi to see his wife and three sons.

We never knew if he had ever intended to return to Red Stone Village. In 1978, my grandfather, who was carrying my baby cousin in his arms, sat down on a sofa, put her down next to him, and died from a heart attack. He was only 62.

It pained me to think how, as a storyteller, how little of my own history I actually knew, and how many stories must have been lost, simply because we had neither the means nor the resources to record them.

I wondered what Red Stone Village must have looked like when my grandfather was a boy, and how he must have run around the same fields that his nephews and nieces now work in. I wondered how he would have felt knowing that one of his granddaughters had made it back to his hometown, to reconnect with his siblings’ descendants.

And I wondered what my own life would have been like, if my grandfather had never left Red Stone Village, or made the sacrifices that he did, so that we would live more comfortably than he ever did.

As the day drew to a close and I left Red Stone Village, I felt, for the very first time, that I had finally met my grandfather.