A Malaysian son's journey to a Chinese village to fulfil Ah Ma's wish

After his mother passed away in Perak, the writer’s father-in-law decided it was time to visit their ancestral home in China – something she was never able to do.

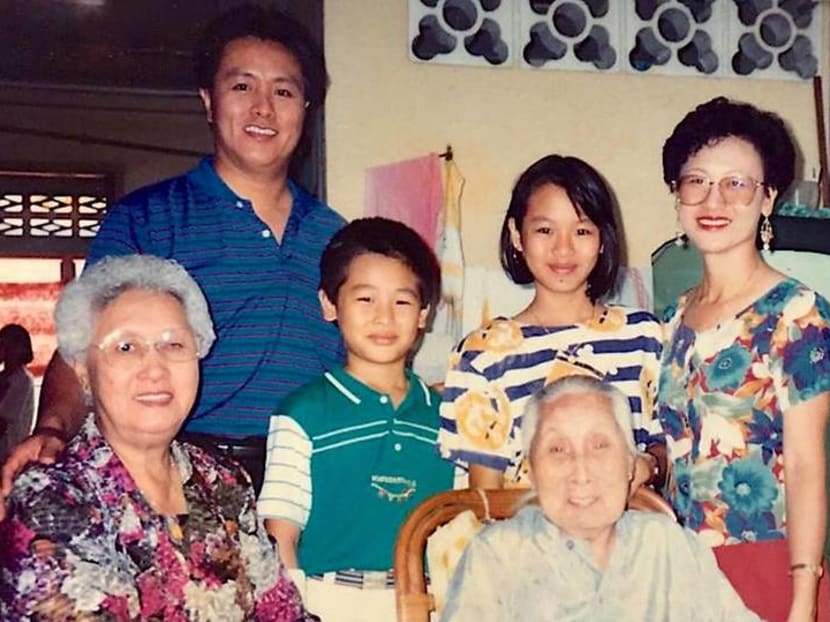

A photo from 1991 of Ah Ma, 67 (front left), with her mother aged 87 during the latter's visit to Teluk Intan from China. Behind are the writer's father-in-law and mother-in-law. (Photo: Victoria Ong)

As we drove past his childhood home in Teluk Intan, my father-in-law Tony Khong declared: “Your grandmother used to rear lots of chickens, so I became an expert in building chicken coops from scratch!”

It was the third day of Chinese New Year in 2019 and Dad was bringing the family around the small riverside town in Perak, Malaysia, where he grew up.

As he shared memories from his childhood, we learnt how his mother Ng Ah Or raised six children singlehandedly while looking after her ageing parents. Ah Ma took on all sorts of jobs, from rearing chickens, ducks and pigs to doing laundry and ironing for others. “Life was so tough for her,” Dad recalled.

His memories were particularly poignant because Ah Ma had just passed away a few months earlier at the age of 94. Despite a hard life, she retained a cheerful disposition even to her final days. While bedridden, she would still muster the energy to smile and chirp “Ah Ma hua hee!” (Hokkien for “happy”) whenever the family gathered around her.

READ: Making the journey back to the little village where my family’s story began

CHANCE ENCOUNTER OVER AIS KACANG

At some point during this trip down memory lane, Dad suggested we cool off with a fruity ais kacang – and it was while queueing up at a busy little stall that we bumped into his 85-year-old uncle Ng Yan Swee, Ah Ma’s younger brother who’s lived in Teluk Intan all his life.

While chatting about how the place had changed since he moved to Kuala Lumpur in the 1980s, Dad asked if his uncle could shed any light on the first generation of Ngs to have migrated from China to what was then Malaya.

It was the first time Dad, a 67-year-old third-generation Malaysian, had felt a keen sense of curiosity about his lineage. Ah Ma’s passing had sparked a desire to find out more about her family history.

Dad’s grandparents were from a small village in Nan’an County in the Fujian Province and had moved to Teluk Intan in the 1920s. He was largely familiar with these facts, but he didn’t expect what came next – the elderly Ng told him their ancestral home in China was still standing and they had the contact details of a relative who still lived there!

It was simply a “divine” discovery for Dad, who had been wondering how he could honour Ah Ma’s memory with a sum of money she had left to her six children.

Born and raised in Malaya, Ah Ma never got to see the country where her parents came from. Despite a lifelong desire to visit China, it wasn’t possible because of financial constraints in the early days, China’s closed doors to tourists from the late 1940s to early 1970s, and her weakened health in later years that made long journeys difficult.

As Dad slurped the last bits of honeydew ais kacang, he decided a visit to the ancestral village “on Ah Ma’s behalf” would be his way of paying tribute to her.

WECHAT AND THE VOYAGE TO THE VILLAGE

“The driver says we are 10 minutes away. I’ll let Teow Kee know all eight of us are about to arrive.” Dad’s text message popped up in our family’s WeChat group chat. I was seated in one of two cars en route to Hong Lai Town in Nan’an County, a 45-minute ride from Jinjiang International Airport in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province.

Six months had passed since Uncle Ng’s revelation and Dad had now become quite the expert in navigating WeChat. He had managed to not only establish his exact relationship to this newfound relative but also coordinate our visit to the village – which was no small feat given Dad neither speaks nor reads Mandarin!

Thanks to a nifty in-app translation tool, Dad was able to communicate with his second cousin Ng Teow Kee. It wasn’t perfect, so in the end, he opted to bring along an entire team of seven amateur translators to China: His wife, three children, two grandchildren and me. Just in case.

At Hong Lai Town, we stopped at a busy Chinese restaurant, situated next to a bridge that stretched over Dong Xi River. The plan was to meet Teow Kee outside the local landmark, so he could lead us across the river into Xi Lin Village where the ancestral home was located.

And it wasn’t long before a middle-aged man waved excitedly in our direction from his ruby red scooter. Tanned and jolly-faced, Teow Kee’s broad smile was instantly recognisable – he looked even more cheerful in real life than in the WeChat photos.

After crossing the bridge, it quickly became apparent why Teow Kee wanted us to follow his lead into the village. Like a funnel, the wide bridge began to narrow before trickling into little lanes. While thinking to myself that navigating this maze was only possible with a local, I was also amused by how clumsy our cars looked next to the deft twists and turns of his scooter. He eventually slowed down outside a metal gate that was wide open. We had arrived.

SETTING FOOT INSIDE THE ANCESTRAL HOME

“I can’t believe we’re actually here,” Dad said softly, as he stepped out of the car and laid eyes on the home of his maternal great-grandparents.

It had a curved roof that seemed to have wings at both ends, a red brick and raw concrete facade, and a pair of grey stone guardian lions seated on top of two sturdy pillars. These distinctively traditional architectural elements stood in contrast to the flat roofs and shiny tiled exteriors of the surrounding multi-storey homes.

Teow Kee officially walked over to shake our hands – but saved the warmest welcome in the form of a big hug for his long-lost second cousin from Malaysia. He introduced us to his mother and nephew and insisted we immediately take a group photo in front of the ancestral home to remember this special occasion.

As we set foot inside the entrance area, I was instantly captivated by the ornate carvings on the old stone walls: Intricate inscriptions and lively scenes of what looked like warriors, scholars and dancers. Further up on the wooden beams were even more beautiful carvings of floral motifs and dragons.

Teow Kee gestured for us to walk under a rectangular entrance arch decorated with striking red couplets, which led us straight into an open courtyard, a space that connected all parts of the house – including the ancestral hall right in front of us.

I caught a whiff of incense as a gentle breeze blew through the courtyard. Teow Kee had lit a few joss sticks for Dad and himself to pay respects to their ancestors. After they had both bowed and placed the joss sticks into a bronze incense bowl, Teow Kee asked if his second cousin could recognise all the faces in the hand-painted portraits hanging above the altar.

Dad stepped closer to the dusty wooden frames, adjusted his spectacles and peered at the black-and-white images of generations past. He was able to quickly identify his maternal grandfather and grandmother (Ah Ma’s parents) but that was all.

Teow Kee smiled and proceeded to introduce the unfamiliar faces: The two gentlemen on the left in the second row were Dad’s granduncles, and the two portraits in the top row were of Dad’s great-grandfather and great-grandmother.

That was the first time Dad saw what his maternal great-grandparents looked like. And as we spent a few quiet moments gazing at the faces on the wall, I wondered what life was like for Dad’s great-grandparents back in the day.

How did they feel about their eldest son (Dad’s grandfather) sailing far away to Malaya in search of a better life? It was hard to imagine the sacrifice of earlier generations, but we were soon about to discover the fruits of their labour.

Teow Kee revealed that the ancestral home was constructed in 1933 – with funds sent from Teluk Intan by Dad’s grandfather, Ng Hoe Kheng. Four different Ng families once lived under this roof, and Teow Kee himself grew up here. While many eventually moved to newer houses, everyone agreed to preserve the ancestral home as a mark of gratitude to that generous granduncle from Malaya.

THE 12-COURSE REUNION DINNER

As we stepped out from the 87-year-old home, Teow Kee introduced us to his son and nephew who were waiting to send us to a restaurant in Hong Lai Town. Teow Kee apologised that not more members of his family were present to welcome us – they were manning the family’s takeaway food stall in town, which he promised to bring us to after “a simple dinner”.

That “simple dinner” turned out to be a 12-course feast featuring local crabs, prawns, abalone, fish, clams and more. As a seaport city, Quanzhou is known for its fresh seafood – and we were treated to an abundance of it. When we told him we were overwhelmed by his generosity, Teow Kee simply laughed and said 12 dishes were considered basic by local standards. Apparently, nothing less would do in their Hao Ke (Mandarin for “enjoys hosting guests”) culture.

Later on, we visited his family’s stall, which specialised in braised innards, but quickly learnt to contain our “oohs” and “aahs” as our hosts immediately took it as a sign to feed us again.

As I took in the sight of this big reunion between two long-lost cousins and their families, I couldn’t help turning to Dad to ask how he felt.

“I feel like we visited on Ah Ma’s behalf and fulfilled her lifelong dream,” he said, smiling. And I could certainly imagine her delighted voice saying: “Ah Ma hua hee!”