So near, yet so far: Aspiring parents and their embryos separated by the pandemic

Border closures have landed a small group of couples in a uniquely difficult situation. The longer they wait, the slimmer their chances of having a baby. But there is now hope.

A technician at work in an IVF centre. Some couples in Singapore can't access their embryos abroad. (File photo: Reuters)

SINGAPORE: After she had a baby boy through in vitro fertilisation (IVF) in Singapore in 2018, health and wellness coach Jamie Alison Kloor and her husband wanted another child.

Her doctor recommended that she head to Malaysia, where she could undergo an embryo screening procedure to improve her chances of pregnancy. This she did in 2019.

The first embryo transferred to her womb did not result in pregnancy. Before she could try again, COVID-19 hit, and the border between Singapore and Malaysia shut in March last year.

Since then, she has been waiting anxiously for the “depressing” travel restrictions to be lifted. “I’m 41 years old, and I can’t keep waiting,” said the American expatriate, whose husband is 46 and Korean. They moved here in 2016.

Kloor, who has three usable embryos in Kuala Lumpur, said she cried whenever signs of a border reopening turned out to be a disappointment. “Every time that happens, you feel you’re getting closer, but then you’re getting further away.”

If not for the border restrictions, “a child might’ve been born already”, she said.

For years, Malaysian fertility clinics have been popular with some Singaporean residents who want children. Treatment costs are lower across the Causeway, especially for women over the age of 40, who do not qualify for some government subsidies in Singapore. Waiting times may also be shorter.

READ: Why Singaporean women are going to Johor to make babies

In the past year, however, a small group of aspiring parents have found themselves in a uniquely difficult situation: Unable to travel overseas but also unable to get their embryos shipped to them. This is because the embryos have undergone a genetic screening that is restricted in Singapore.

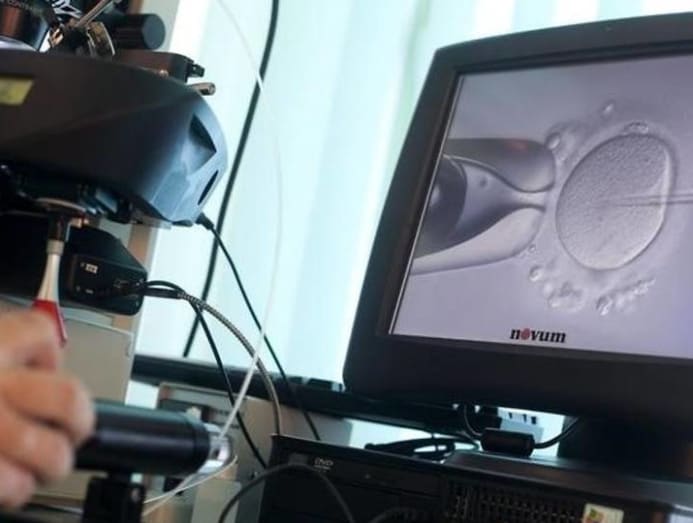

Called pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS), it improves the chances of a successful IVF pregnancy. It screens embryos for the correct number of chromosomes before they are transferred to the womb.

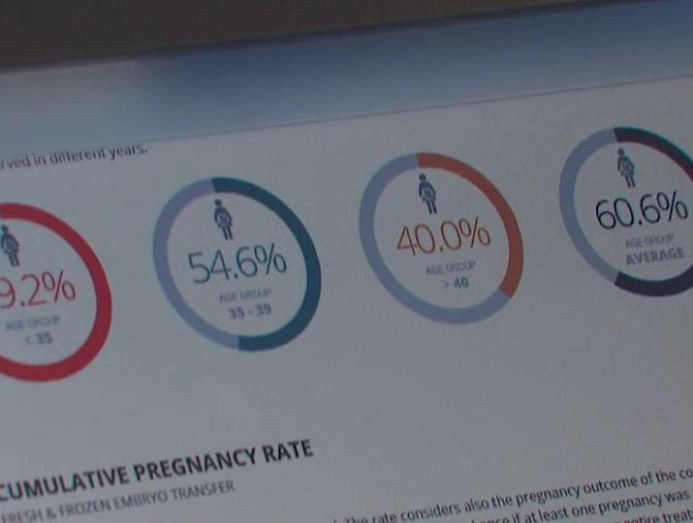

The success rate of conventional IVF is about 20 to 30 per cent. But with PGS, advocates say, the chances of pregnancy can range from 70 to 90 per cent.

In Singapore, PGS is allowed only in a pilot programme involving nearly 400 patients at three public hospitals. Participants must meet one of three criteria: Be aged 35 or over, have at least two recurrent implantation failures or at least two pregnancy losses.

Also known as pre-implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy, PGS is not without risk or ethical implications. It carries a small risk of damage to the embryo and allows for gender selection. But the latter can be overcome by not disclosing the embryo’s gender to patients.

APPEALS POSSIBLE

Couples with PGS-tested embryos stranded overseas now have a glimmer of hope. The Ministry of Health (MOH) disclosed in March that it “may on an exceptional basis allow importation of the embryos, subject to conditions”.

It was responding to a question from Member of Parliament Louis Ng, who had asked if such embryos could be allowed into Singapore given the travel restrictions.

The ministry told CNA Insider that as of May 21, it has received 17 appeals to import embryos stored overseas, including Australia, Malaysia and Taiwan.

It has allowed four appeals provided that “stipulated requirements are met”, and is reviewing 12 appeals. One that “didn’t meet regulatory requirements” has been rejected.

The MOH assesses each case based on the individuals’ medical need and particular circumstances, a spokesperson said.

It also considers whether the relevant processes and standards of the overseas centres, as well as the local centres receiving the imported embryos, meet Singapore’s regulatory requirements.

“These include the adherence to age limits if any donor gametes are used, and the prohibitions against non-medical gender selection and commercial trading of gametes and embryos,” the ministry said. Gametes are eggs or sperm.

Local fertility centres must ensure that the embryos are packaged and transported in a way that minimises the risk of contamination, among other requirements, the MOH added.

EMOTIONAL ROLLER-COASTER

CNA Insider spoke to four individuals with PGS-tested embryos in Malaysia. Until Ng’s parliamentary question, they were unaware that they could appeal. Two of them, including Kloor, have done so and are waiting to hear from the authorities. The other two said they are keen to appeal.

A 40-year-old chief financial officer who wanted to be known only as Chen said she did PGS testing in Johor after having a failed IVF cycle in Singapore.

“IVF is like an emotional roller-coaster. I heard that if we go for a PGS test, the likelihood of success might be higher,” she said. “I also wanted to save time because after every unsuccessful IVF (cycle), you have to rest for one or two months.”

Chen, who said she and her husband have unexplained infertility, has four embryos stranded across the Causeway.

With the pandemic continuing unabated, she decided to undergo IVF in Singapore again and had her second failed cycle, in March. While she qualifies for the local trial, she has been told that the earliest she can do PGS testing is in December.

She does not know the gender of her embryos and will “definitely” make an appeal to ship them from Malaysia.

Another aspiring parent, a 34-year-old analyst who declined to be named, said he and his 32-year-old wife began fertility treatment in Singapore in 2018. After two miscarriages, they found out that he has a chromosomal condition that increases the risk of miscarriage.

When two transfers of embryos did not result in pregnancy later on, the couple sought treatment in Malaysia. They completed three rounds of egg retrieval (where eggs are removed from the ovaries to be fertilised) and made it home just before the border shut last year.

They learnt that their PGS treatment had yielded some normal embryos. However, unable to visit Johor ever since, their parenthood quest has been disrupted. After suffering another miscarriage, the couple opted to go through IVF again in Singapore.

“As we get older, the chances of conceiving get worse and worse,” said the analyst. “Because my PGS embryos are stuck in Malaysia, I’m forced to go through a few more rounds (of IVF) in Singapore.”

IVF involves many tests, injections and hormones to induce the production of more mature eggs. One round can cost between S$8,000 and S$12,000 before government subsidies.

PGS is not cheap either. The MOH recently said it has extended S$1.7 million in PGS funding, for example for manpower and laboratory operations. Trial participants pay about S$1,100 for consumables per test and S$2,500 to S$4,500 for embryo biopsy to remove cells for PGS testing.

A RACE AGAINST TIME

Unlike the other two interviewed above, Kloor knows the gender of her embryos because the clinic disclosed the information without her requesting it.

She has been upfront about this detail, and stressed that she did not undergo PGS to choose her baby’s gender but because she had lost three frozen embryos during the defrosting process previously.

READ: The egg freezing dilemma of women in Singapore

“I’m appreciative of the MOH looking into it … and listening to us,” she said.

CNA Insider contacted four Malaysian fertility centres that see patients from Singapore. Three of them — Alpha IVF, IVF Bridge and TMC Fertility — declined to comment.

Sunfert International Fertility Centre in Kuala Lumpur said it does not practise or condone gender selection.

But as PGS tests all 23 pairs of chromosomes for abnormalities, the sex chromosome make-up is included in the report unless patients request otherwise, said Sunfert Group founder and director Wong Pak Seng.

If the sex chromosomes are abnormal, there may be physical and developmental problems that may not be diagnosed until puberty, he said. “We routinely ask patients at the beginning of the treatment whether they want the gender to be revealed.”

Since March last year, Sunfert has had five patients, aged 38 to 45, who would like to ship their PGS-tested embryos to Singapore. The MOH has asked the centre for more details, Wong said.

Sunfert has shipped two unscreened embryos to Singapore since the borders closed. This is similar to previous years, and shipping costs roughly RM3,000 to RM4,000 (S$960 to S$1,290), he added.

It is a race against time if a pregnancy does not result from all the viable embryos, noted the fertility specialist. With age, couples have fewer eggs that can produce babies, diminished egg quality and a greater risk of complications.

The MOH said it “understands the challenges faced by couples under the current situation, and will facilitate the appeals where possible”.

Of the 370 patients recruited for its PGS pilot programme since 2017, only 120 have had their embryos tested. The high attrition rate is because some patients changed their minds and transferred embryos to their wombs without doing PGS, or froze their embryos instead.

WATCH: Rahayu Mahzam on pre-implantation genetic screening

PGS differs from another procedure called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), which caters for those who may pass certain inheritable diseases to their children.

Singapore has had a PGD pilot programme since 2005, and it became a mainstream clinical service this month. It is now called pre-implantation genetic testing for monogenic/single gene defects and pre-implantation genetic testing for chromosomal structural rearrangements.

Owing to his chromosomal condition, only the PGD testing has been available to the analyst and his wife. But their fertility treatments since late last year have cost more than S$30,000, as they have maxed out their government subsidies.

They now have a few embryos here, but they want to ship their embryos from Malaysia as a “backup”. They have appealed and are waiting to hear from the MOH.

“I’m doing (PGS) for medical reasons,” said the analyst. “I daresay for people doing PGS, most aren’t there to choose the sex but to ensure that the embryos they’ll transfer are normal.”

Editor's note: The main photo for this story has been changed. The previous photo showed embryonic stem cell therapy instead of an IVF procedure.