Squid Game ang ku kueh? Hokkien, Cantonese, and Teochew classics get a modern makeover

Meet the folks from 1925 Brewing Company, Tong Heng bakery and Ji Xiang Confectionery, who are introducing their dialects’ cuisines and customs to a new generation the best way they know how – by feeding them.

From left: Cantonese pastries, Teochew braised duck and Hokkien ang ku kueh (ala Squid Game). (Photo: Tong Heng, 1925 Brewing Company, Ji Xiang Confectionery)

Traditionalists may baulk when they pass Kelvin Toh’s ang ku kueh store along Victoria Street.

Here, the traditional Hokkien tortoise-shaped cakes come in a literal rainbow of colours. There are pretty pastel-hued kueh, some flecked with gold, and yet more in the shape of Squid Game characters wearing distinct pink sweats and black masks. (They even hold workshops to make these.)

His mother, Toh Bong Yeo, the matriarch of their well-known family business Ji Xiang Confectionery, has been known to roll her eyes at the sight of these… well, travesties.

Mrs Toh has been making and selling ang ku kueh for more than 30 years. As far as she is concerned, ang ku kueh should be tinged red or a single specific colour to convey an occasion and retain its tortoise-shaped mould which symbolises longevity and good fortune. Traditionally used for prayer offerings and birthday celebrations, ang ku kueh is a cherished part of the Toh family’s Hokkien culture.

But her 40-year-old son has different ideas. “We are in the business of traditional Chinese pastries, so there’s a lot we can do to educate the next generation and the generation after them. Nowadays kids know Japanese mochi, but they don’t know what is ang ku kueh," said Toh.

When he was given the chance to start a branch of Ji Xiang in Victoria Street, he jumped at it despite his family’s reluctance. “My store faces Bugis Junction, which is an area with a young, trendy population. Then there’s an old temple behind it,” he explained. “It’s really the perfect location for me to capture both the young and older crowds.”

Making ang ku kueh in attractive colours and forms is simply part of his quest to capture the attention of a younger generation who wouldn’t otherwise be drawn to this old world confection.

“If you don’t catch their attention, you can’t educate them. So we try to mix things up and create more hype,’ he said. Once aware of the delights of ang ku kueh, perhaps the new audience might be compelled to delve into its history and symbolisms.

Case in point is a ceremony that sees a one-year-old child stepping on an oversized pair of ang ku kueh before stepping into a pair of new shoes. “It was not a family tradition for us, but when my daughter was invited to do it for a TV show in 2015, I was very moved by it and wondered why this tradition has mostly been forgotten,” said Toh.

Since his daughter’s turn on TV though, sales of ka ta kueh or oversized ang ku kueh tailored for the rite has grown exponentially. Seeing younger parents embracing this tradition has been heartening for Toh.

“I want to break this misconception that ang ku kueh is just for prayers. It’s a delicious kueh that’s good for teatime. I want the younger generation to know that you don’t have to buy a rainbow cake or a chocolate truffle for a (treat). Your roots are here and it can be just as delicious.”

BAKED INTO TRADITION

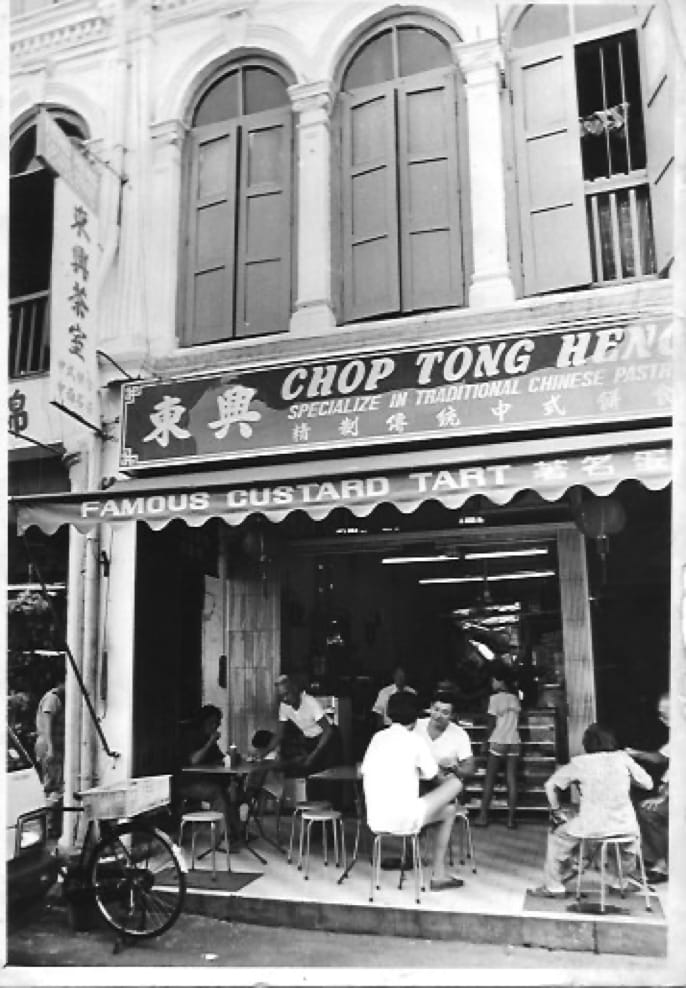

Ana Fong is another scion of a traditional Chinese bakery with cherished roots in Singapore. Her great grandfather Fong Chee Heng began peddling his Cantonese pastries from a pushcart in Chinatown in the 1920s before setting up shop at Smith Street in 1935. In 1983, when the government acquired Smith Street, Tong Heng moved to South Bridge Road where the family continues to ply their trade.

Fong, who is in her 50s, began working full-time at her family business 10 years ago when she realised that her aunts, who run the business, were ageing. The idea was not to take over the business, but to learn how to produce her family’s popular baked goods.

During her breaks from the kitchen, she observed that much like her aunts, many of the store’s customers were getting along in years. “I realised that in order to continue the brand, we need a new audience,” she recalled. It took three years before her aunts agreed to a facelift and in 2018 Tong Heng re-emerged with a more contemporary mien, both at the store and as a brand.

The update isn’t just about appealing to a new audience; Fong hopes that her family’s business can help teach a new generation about traditional Chinese practices.

“It’s not uncommon that many people are not able to count from one to 10 in their dialect. What more their traditions and values? My point is that the millennials of today, and even parents, are not very strong with the understanding of (Chinese customs). We have couples coming in before they get married and their parents are clueless about what to do,” she said. “I believe (what we do) helps people continue with their wedding traditions.”

In the works is a collaboration with heritage researcher Lynn Wong that will see Tong Heng producing Toi Shan-style wedding pastries as part of the Toi Shan Festival in December. There will also be a short talk about how traditional Chinese wedding customs have been simplified today.

“In the last 10 to 20 years, people would just settle for things like traditional decor… they just sign the wedding papers (without many of the traditional rites),” she explained. “With COVID-19, even the wedding banquet has been cancelled… Even if (participants) don’t do it, at least they are aware of what happens (at a traditional Chinese wedding).”

PRESERVATION BY MODERNISATION

For 40-year-old chef Ivan Yeo, the impetus to preserve his Teochew roots came when he opened his second 1925 Brewing Company outlet in Joo Chiat Road in 2017. He arrived to find more than a few traditional Chinese restaurants in the neighbourhood shuttering due to manpower or succession issues.

“I dug deeper and found that the manpower issues were more of a consequence of something we practice in Chinese kitchens,” he said. “We are chained to upholding traditions such as having only Chinese people in the kitchen, and I wanted to change that.”

Yeo set about diversifying his staff, employing anyone who was interested in Teochew cuisine. He then modernised his kitchen’s arsenal, doing away with woks, ladles and choppers, and in their place installing machines like a combi oven, Thermomix and sous vide circulator. “We take a technique-based approach rather than the old, romantic one, like agar-ration (Singlish for estimating),” he said.

“We started to package food that is more refined when it goes to the table. Youngsters don’t want Chinese food in some dodgy place with Chinese music. You want to make it sexy and modern, so you have to embrace the whole package.”

Yeo’s late grandmother was, by his account, a well-known hawker who sold traditional Teochew braised duck, the recipe for which died with her. This, along with the sentimentality that comes with age, triggered an urgency to preserve his Teochew identity through food.

His rendition of this cherished dish has long been on the menu at his restaurant alongside modern takes on Teochew classics like his Chaoshan ceviche — raw fish cured in salt before it is served on a bed of cabbage, citrus juice, chilli padi and a dab of sesame oil.

Educating a new generation through food isn’t always a viable business, though. Next week, 1925 Brewing Co at Joo Chiat will be rebranded to Blue Smoke, featuring food cooked over open fire. The Teochew aspect of his food will then become a subset of the new smokehouse offerings.

“It’s really a business decision. I’ve been fascinated with Texas cold smoke over the last two years and I’ve found that it’s suitable for Asian dishes. This is just an extension of what we have always been doing, furthering Chinese and Asian food from a different context.

“The kind of food we do is an expression of our own childhood,” he continued. “I’m trying to do my bit to preserve the memories I had with my grandparents. Maybe one day, I’ll visit China to learn how our dishes evolved from China to Southeast Asian and to Singapore’s version.”

Learning the past, after all, is the best way to learn how to move forward.