Subtitles and captions on local TV shows: Who does them? And what's the hardest part of the job?

What goes into producing captions and subtitles in dramas like Unriddle, Tanglin and Cash On Delivery, and what are the biggest challenges and satisfactions of the job? CNA Lifestyle finds out from three Singapore subtitlers.

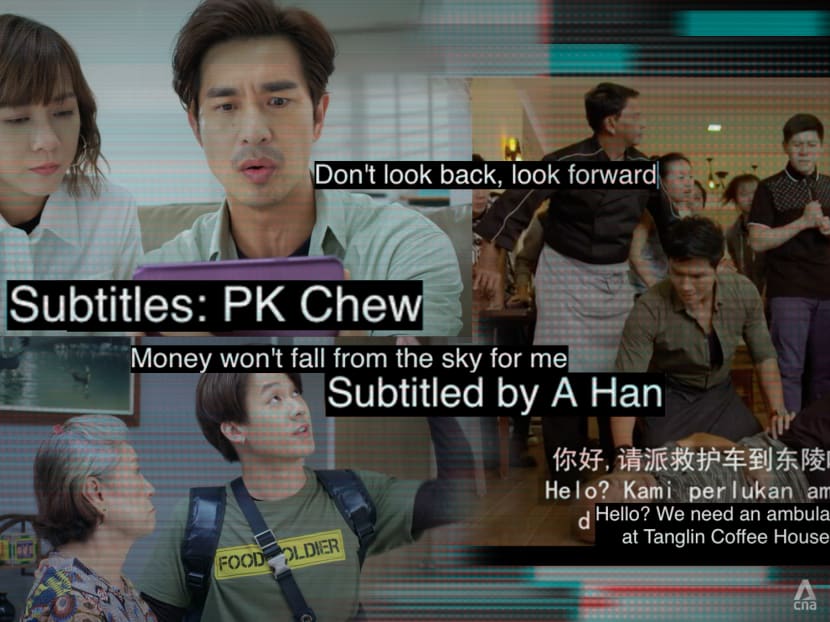

Who are PK Chew and A Han? Meet the people behind the scenes. (Art: Chern Ling)

When I was a kid, there were only a couple of channels on television – you know, back in the era when dinosaurs roamed the earth. We all watched programmes in English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil, because there were always subtitles on free-to-air TV shows. For a period of time, my mother, in hopes that my Mandarin skills would improve, taped strips of paper onto the screen to cover the subtitles, reasoning that watching Channel 8 dramas would be an immersive language-learning experience for me. (It did not work.)

These days, with films and series going global, subtitles are perhaps more important than ever. Have you ever wondered, though, who creates these subtitles, and what work goes into getting them onto your screen?

If you’ve watched enough local dramas, you’ll have noticed a few familiar names regularly popping up in the subtitling credits.

Who is “PK Chew”, for example, a fixture in Mandarin-language dramas and variety shows? She’s actually Chew Pueh Keng, 49, who has been doing subtitling work for television for over 15 years. In the course of that time, she’s subtitled over 270 dramas and infotainment shows, and vetted countless more. She finds suspense dramas the most interesting to work on, such as 2010’s Unriddle, starring Rui En and Chen Liping.

Then there’s Ann Han, 51, whose subtitling career began over 25 years ago when she responded to a print recruitment ad by the then-Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS) for TV subtitlers in 1997. She landed the job after taking an aptitude test and an in-person interview. She particularly loves working on Mandarin medical, suspense and period dramas.

Subtitling doesn’t always involve translation. Habib Shah, 34, does same-language captioning for English dramas, current affairs shows, info-ed programmes and even movies.

He’s spent eight years on the job, after stumbling upon it as a fresh graduate sifting through job descriptions. “Since I have always enjoyed watching TV shows from a young age, I just took a chance!” he said. One of his favourite projects has been Tanglin, Channel 5’s first long-form drama. “It involved plenty of characters and newer characters that were introduced subsequently, which made the story line really interesting.”

While it may appear straightforward on the surface, subtitling is a job that’s not well understood and often underestimated. Like many other roles, you probably only really notice it when it’s badly performed.

“Subtitlers don’t translate literally or just deliver the words,” Chew said. “We identify the intended meaning and translate in a way that expresses the meaning. And to do that consistently takes more than language proficiency.”

Subtitling is a job that’s not well understood and often underestimated. Like many other roles, you probably only really notice it when it’s badly performed.

Having a language degree is helpful for the job, but on top of that, you also need to have a keen eye for detail, cultural awareness and good time management skills, all three said.

But there is satisfaction in knowing that their efforts can enlarge the audience that is able to approach a filmic work. “One of the most fulfilling aspects of this job is the opportunity to enhance accessibility,” said Habib – in his case, especially for individuals with hearing impairments and the elderly. “The knowledge that your work has played a role in improving accessibility and promoting inclusivity for these individuals can be immensely gratifying.”

HOW IT WORKS

Han recalls how she started with VHS tapes back, before going digital around 2008 or 2009.

"A small TV set, a VCR player and a PC were our trade tools," she shared. "We had to manually rewind the tape on the remote control to get the precise timing for the in-time and out-time of a dialogue. Timecoding was tedious back then. We manually entered the minutes, seconds and frames for each subtitle.”

She also recalls that her office “used to have a mini library with reference books for our use – dictionaries, the local road directory, world map, glossary of food names, etc. I’d also make trips to the National Library on some weekends to do my research, in pre-Google days”.

Today, “We just need a laptop and a monitor to play the videos and run the subtitling software. The work desk is a lot less cluttered now,” she said.

What does the actual day-to-day work look like? “We translate based on the video and refer to the script when necessary,” Chew said. And, “We use a subtitling preparation software that enables us to timecode and translate lines.”

Scripts are referred to if the subtitlers need to verify certain terms and names used, or if the dialogue is unclear. "I always have the script open,” Han said.

A one-hour drama episode, Chew said, “typically takes up to three days to translate and review. Info-educational shows may take even longer because of the research work that goes into fact-checking."

And while they do get to work from home, they still head to the office for meetings and events.

Subtitling is not simply translation of words or phrases. There is a lot of mental work involved.

Habib told us that he currently uses some AI tools to help with English drama captioning, which cuts down the turnaround time by about 30 per cent. One of the biggest challenges is working within tight deadlines, as “the television industry moves swiftly, requiring us to constantly stay updated on programme changes and take immediate action to ensure timely provision of subtitles”.

“I truly believe that in the near future, ASR (Automated Speech Recognition) software will help us do our jobs more quickly and efficiently,” he said.

Still, at present, “accuracy, precision and localisation are still lacking”, Chew said. AI is still “unable to capture the nuances of a language, its unique idioms and cultural references”.

Han thinks that in time to come, AI "will certainly replace human input. But, it also means that we need personnel of caliber to review and edit the AI-generated files”.

THE HARD BITS: WORDPLAY, HUMOUR AND SINGLISH

The challenges of the job are particular, but so is the satisfaction in overcoming them. These include “retaining the nuances in the original language in the translated language; cultural differences between source and target language output; time constraints, as we only have a few seconds to put the idea across succinctly and subtitle lines must sync with the audio; keeping the prescriptive language alive without coming across as stilted; and (finding) the lexicon to suit the occasion and status or identity of the speaker or role,” Han said.

“Subtitling is not simply translation of words or phrases. There is a lot of mental work involved.”

For instance, “Puns and wordplay in one language don’t always translate well into another”, Chew said. “To get around it, we may have to use different references.” Han agreed: “It’s a challenge to avoid ‘lost in translation’.”

For Habib, whose job scope focuses on same-language captioning for English programmes, another challenge is "deciding whether to retain Singlish and non-English terms in the English subtitles of dramas, or rephrase them".

He explained: "Striking the right balance is crucial, as we don’t want to overcorrect, but we must exercise judgment and draw upon our experience to determine when it is appropriate to leave these terms as they are and when they should be rephrased… Preserving the local essence while maintaining the intended meaning can be tricky."

He added: “When we first started same-language captioning in 2015, it was uncharted territory for us and we set ground rules on how strict we were with using local terms such as ‘Ah Gong’ (Grandpa), ‘sayang’ (my dear), ‘thambi’ (younger brother) and ‘kopi' (coffee). We used to translate them to English terms as we were afraid that viewers might not be able to accept them.”

But now, they leave these non-English terms in the subtitles "as they are common local terms that viewers can understand, and this encourages inclusivity as well”.

Language, of course, is always evolving. In addition to what’s acceptable in prevailing society at a certain point in time, subtitlers also need to keep up with newly coined terms or changes in meanings of words, said Han. "We conscientiously do our online research."

For instance, Chew pointed out that one of the ways in which the growth of social media has influenced the English language is the appropriation of existing vocabulary. “For example, if a Gen Z-er flaunts in an ostentatious way, in the past, we might say, ‘What a show-off!’, but now, we could say, ‘No flexing!’.”

What’s more, “In recent times, the use of informal – but still grammatically accurate – language is also more acceptable. Where appropriate, it helps capture the casualness and spontaneity of everyday speech. For instance, ‘He’s acting pretty sus’, with the shorthand ‘sus’ for ‘suspect’."

“Difficult technical terms or esoteric subject matter can also be challenging,” she added.

But in the end, Han said, all the hard work “contributes to creating content that is not only of good quality but that also can be enjoyed by more audiences”.

After the show goes out, “Receiving positive feedback from viewers is highly rewarding as it acknowledges the dedication and effort put into delivering top-notch subtitles,” Habib said.

Above all, “Getting into the mind of every character and being their voice” in a different language brings a sense of achievement, Chew said. “Storytelling is multicultural, and there’s a lot of satisfaction in seeing subtitles bridge different cultures and languages.

“Subtitles are not the one-inch-tall barrier any more, as (Oscar-winning Korean film) Parasite showed emphatically.”