From text to touch: The braille centre in Singapore helping the visually impaired connect with words

With October a significant month for visually impaired awareness, CNA Lifestyle tours the Singapore Association of the Visually Handicapped to understand the unique considerations in producing braille material from exam papers to public signs.

Jason Setok lost his vision at 27, and now supervises the Braille Production Centre at the Singapore Association of the Visually Handicapped. (Photo: CNA/Jeremy Long)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Having optimal space matters to the visually impaired, in more ways than one.

There is, most obviously, physical space. At the Singapore Association of the Visually Handicapped (SAVH) in Toa Payoh, the corridors are straight and wide, with 90-degree angle corners. Its clutter-free floors lend an overall spartan appearance, seemingly inevitable in a place where function trumps form.

The area is relatively easy to navigate for visually impaired employees, like Jason Setok, supervisor at the association’s Braille Production & Library Services Centre.

The 46-year-old, who’s worked at SAVH for nine years, is familiar with the route from his office to the Braille Production Centre, a room roughly 30 steps away. He doesn’t need a cane for his trip down the hallway, finger-tapping on walls to alert colleagues who may be nearby as he takes us on a tour of his modest workspace.

All things considered, it seems a gentle learning curve compared with picking up braille when he lost his vision at 27 due to glaucoma. He took five months to master it.

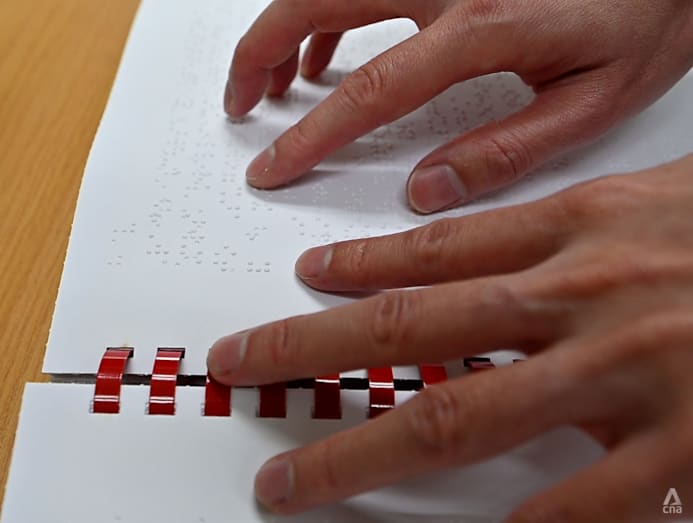

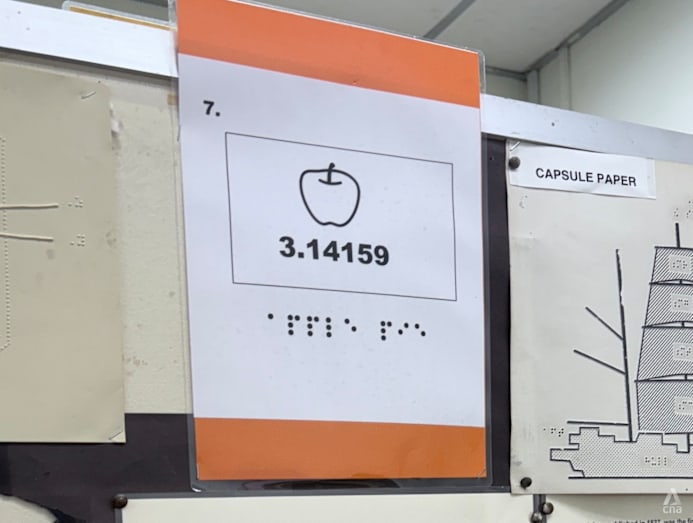

Developed by French educator Louis Braille in the 1820s, braille is a tactile writing system comprising raised dots that help visually impaired people to read and write.

You may have seen (or felt) it on public lift buttons and toilet signs in Singapore, but perhaps not educational material like the ones that Setok and his team produce.

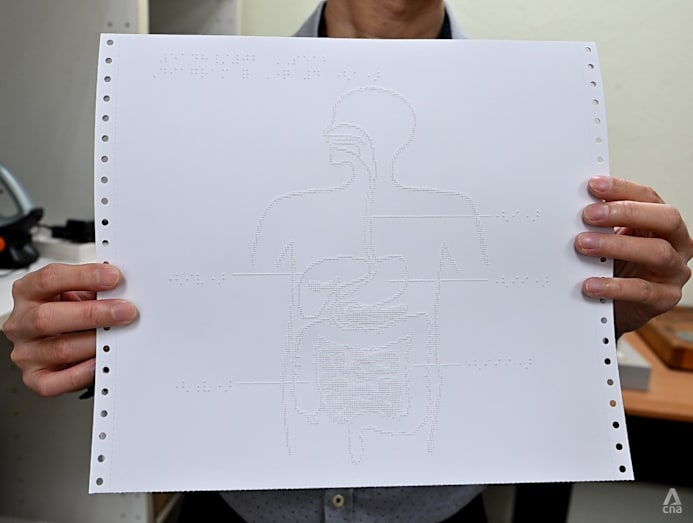

Aside from converting reading material in English into braille, the centre also produces tactile diagrams – the 3D representation of the print image using raised lines and dots – and braille signage, embosses braille on print name cards, and offers braille auditing services.

SAVH estimates there are about 40,000 people who are visually impaired in Singapore. It has served over 4,000 to date, with most referred from healthcare institutions like public hospitals.

Learning braille may prove especially tricky for those who lose their sight when they're older, because of the lack of "sensitivity" in their fingertips, Setok said.

This is compared with those born blind, who hone an acute sense of touch from young out of necessity.

Those who are used to relying on their vision might not be able to “feel the braille” when they start learning, even if they know the dot pattern for each letter.

Though braille is available for reading in different languages in Singapore, the centre only produces English materials.

BRAILLE SPACING KEY FOR LEGIBILITY

Where space for the visually impaired is concerned, the spacing in braille material – from public signs to school books – is equally consequential, though perhaps overlooked by the sighted, in everyday life.

“Wrong” spacing is often created by those who don’t understand the dot-pattern font in the first place, even though the Braille Production Centre does its best to advise its corporate clients ranging from government agencies to private companies.

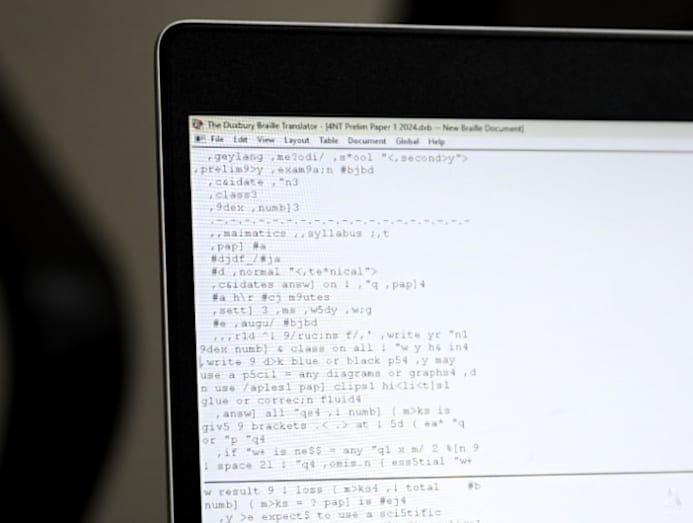

Clients often send in the exact wording for signage requests in a Microsoft document – “female toilet”, for example – which Setok and his team convert into braille in a soft copy file. This file is then returned to clients, who emboss it on their end.

It is the final step that occasionally goes awry.

“Sometimes, the production … results in wrong spacing of the braille. Or even the font size of the braille, they try to shrink it in a way that’s smaller than actual braille,” he said.

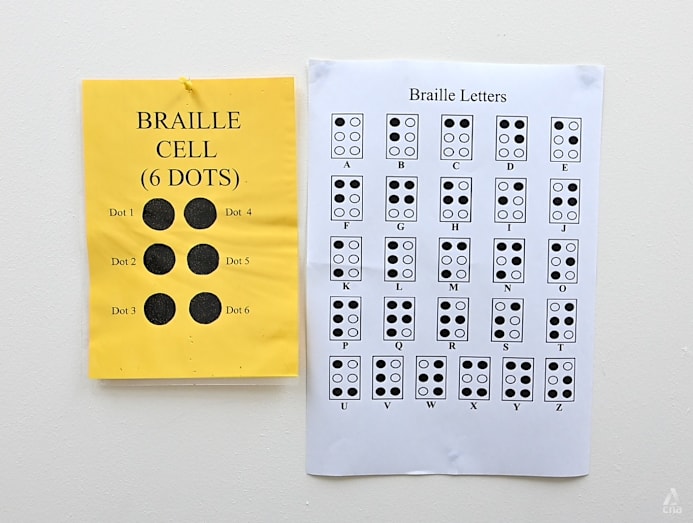

Braille is considered a fixed-width font. Each character occupies the same amount of space, regardless of how many dots are in the cell. A full cell is three dots high and two dots wide, and may contain up to six dots in total.

Its structural nature means the individual dots can’t be made smaller. Spacing between dots can't be tightened either.

Altered font size would be “misleading”, he explained. “If you were to cram everything together, there’s not much spacing and we’ll be confused. That word (won’t) mean anything to us.”

And so when it comes to storybooks, this means one Harry Potter paperback instalment, for example, would be much larger and heavier (around 10kg) once converted to braille.

One side of a sheet of braille paper measuring 11 inches by 11.5 inches can hold around half the words from a single A4-size page, Setok estimates.

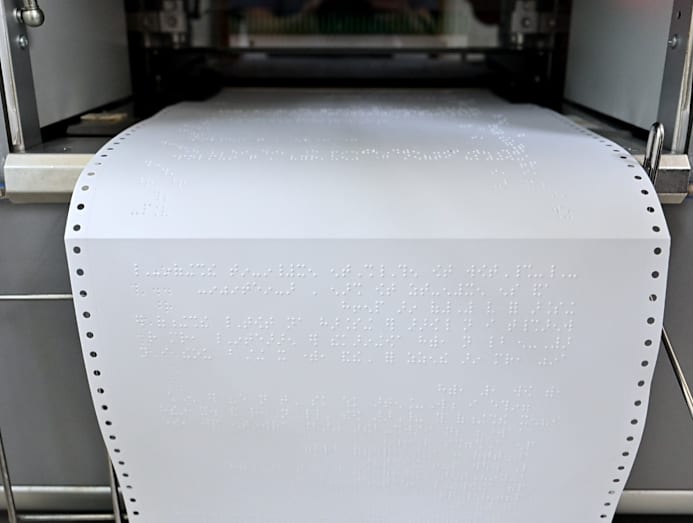

PRODUCING BRAILLE TEXT, TACTILE DIAGRAMS

The same meticulous approach is used when the Braille Production Centre works with mainstream secondary schools to convert print materials into braille and tactile diagrams.

The three schools in Singapore currently able to cater to visually impaired students are Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School, Bedok South Secondary School and Dunearn Secondary School, according to the Ministry of Education’s SchoolFinder function.

The centre mainly serves Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School, which Setok estimates has four visually impaired students.

Learning materials for primary school students are produced at Lighthouse School, a special education school owned by SAVH and located within the same campus. It caters mainly to students aged seven to 18 with visual impairment and hearing loss.

Setok’s team of five – three are visually impaired including himself – receive requests from schools to convert textbooks, exam papers and daily assignments into braille. Depending on the level of urgency, they either wholly produce and deliver the materials or send the school a soft copy braille document, which the school then embosses on their end for lessons.

Despite the prevalence of assistive technology, most of which have audio features, Setok still sees the value in learning braille for communication.

Learning the braille writing system is akin to learning, say, English by reading and writing in the language from young. It teaches the fundamentals.

“Spelling is very important … In braille, you can feel the wording or learn to spell on the paper. Just like how (those who are born sighted) see words on the paper, we feel on the paper. That’s why it’s still relevant,” he said.

In any case, schools still require visually impaired students to answer in braille.

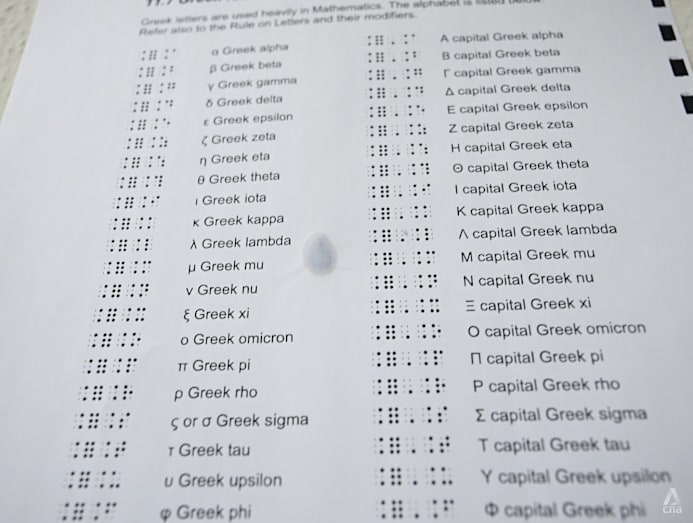

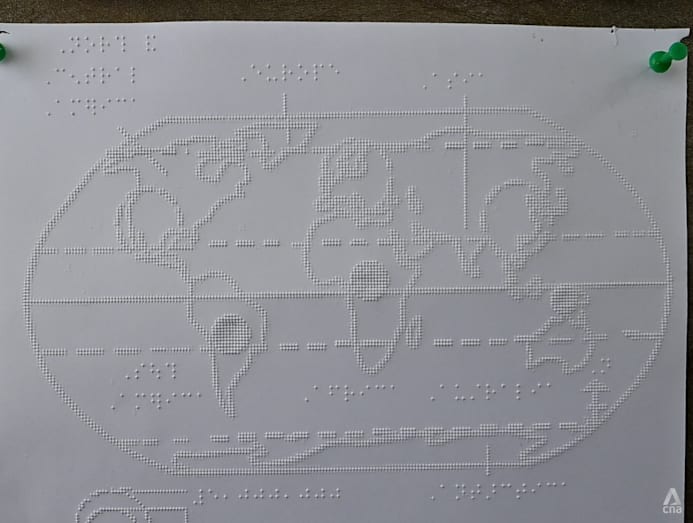

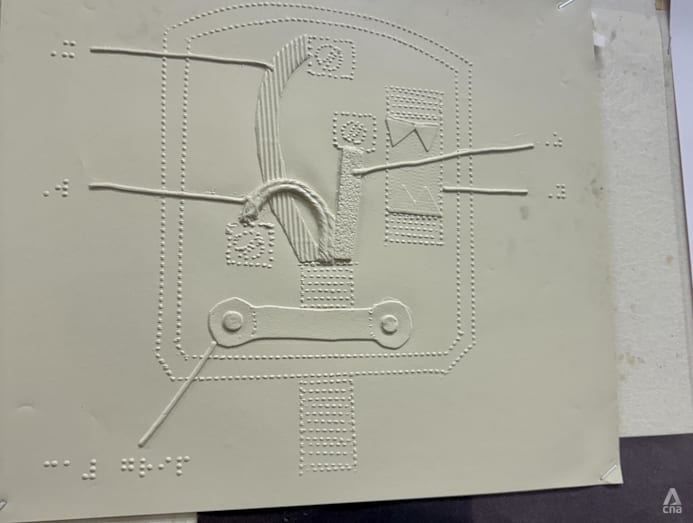

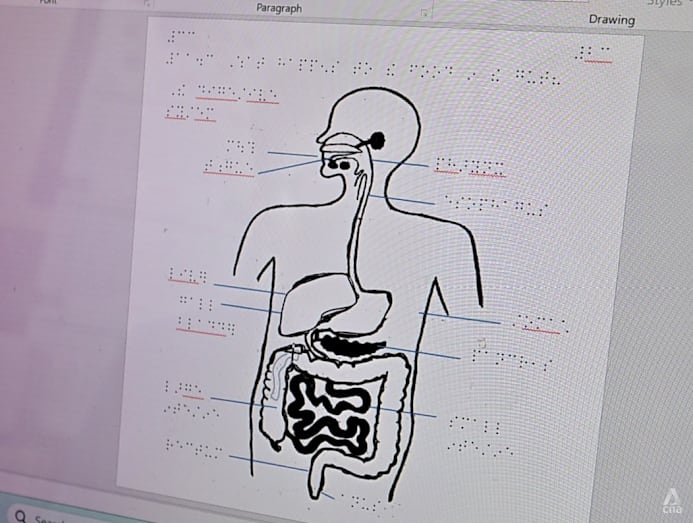

Educational diagrams, from science to math and geography, often contain text and images.

The text that’s translated to braille may need to be positioned differently on the tactile diagram – the 3D representation of the print image using raised lines and dots.

In a math diagram about angles, for example, labelled angles may fall within the diagram in its print version. But once translated into braille, they could be placed outside the diagram or elsewhere on the paper for accuracy purposes.

To a visually impaired student, “squeezing” braille dot pattern into the exact spot on a tactile diagram is akin to an erroneous placement of text for the sighted. They may be unable to read the question at all.

“So we have to be precise,” Setok stressed.

“Sometimes, we will even have to draw dotted guiding lines (that are not in the original paper) pointing to a particular section (on the diagram), so the students can feel which (braille text) refers to which part.”

Producing the tactile diagram itself also requires similar careful precision. If a diagram is embossed “wholesale”, it could carry over “unwanted dots” from its print version.

Think of these “dots” as specks of ink that can show up on photocopied material. They’re typically immaterial to a sighted person’s understanding of the diagram.

But in producing a tactile diagram, these “dots” – along with unnecessary visual attractiveness – are first edited out on Microsoft PowerPoint to create a “simplified version” of the print diagram.

The team will always attempt to mirror the print diagram “as closely as possible”, unless it’s unnecessary.

For example, a tactile diagram of the human digestive system shouldn’t replicate artistic shading used to convey realism from its print version, since that element isn’t required for the visually impaired to comprehend the diagram.

“Or maybe it’s just an airplane flying or taking off from the runway (in the original print version). We will not draw that diagram, because the picture doesn’t have answers linked to the question,” added Setok.

“We’ll just describe it in braille text for (the visually impaired student).”

The amount of editing usually depends on the “complexity” of the diagram. In some cases, the team even draws it from scratch.

Once finalised, the diagram is sent to a ViewPlus, an unassuming machine that’s responsible for a whole nation’s high-quality tactile diagrams.

It's not a contraption anyone sighted would be familiar with, much like the existence of the Braille Production Centre itself. But for the visually impaired, braille can be a lifeline.

It was Setok's. Before his sight deteriorated, he worked at consumer electronics giant Philips, where he tested plasma TVs and did soldering on circuit boards. He lost his job, and within three years, his entire ability to see.

And yet, with braille, he’s not completely blind.