What’s it like getting your portrait taken by a Deaf photographer in a silent studio session?

Photographer Isabelle Lim will offer portrait sessions conducted entirely through non-verbal interaction at the Enabling Lives Festival on Dec 6. CNA Lifestyle tried it firsthand.

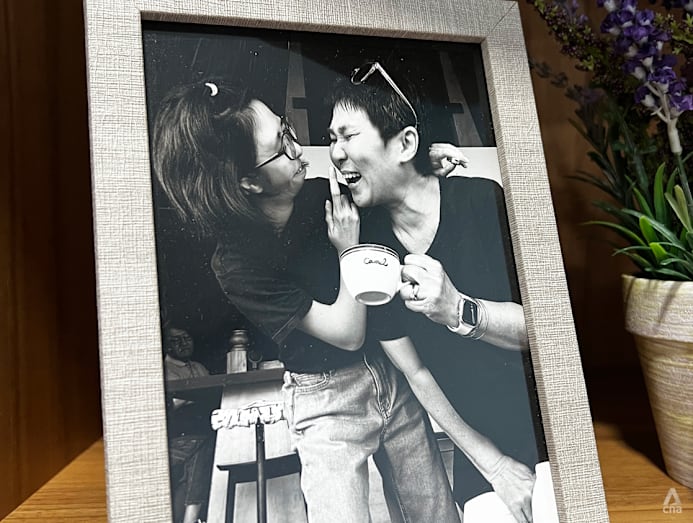

CNA's Grace Yeoh and Jasper Loh attended a silent studio portrait session with Deaf photographer Isabelle Lim on Nov 27, 2025, in the lead-up to her showcase at the Enabling Lives Festival on Dec 6. (Photo: CNA/Jasper Loh)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

You assume you’re comfortable with silence after almost a decade of being a journalist.

Interviewees don’t always open up the way you hope they would, but silence comes in shades – the considered pause of someone working through their thoughts versus the taut quiet of someone uneasy by what they aren’t quite ready to reveal.

Eventually, you stop trying to fill it. I thought I'd become an expert at listening to words unsaid – until I was the subject.

About to get in front of the camera for a portrait session on Thursday (Nov 27) that would be conducted entirely through non-verbal interaction, I felt the familiar twinge of self-consciousness I thought I’d left behind in my early 20s.

I had too many questions for the photographer, and no way to get my answers. At least not in the traditional sense.

MEETING A DEAF PHOTOGRAPHER

Behind the lens was Isabelle Lim. Born with Nager syndrome, which is characterised by craniofacial and limb abnormalities, the rare genetic condition has also made her profoundly deaf since birth.

Individuals with profound deafness can't hear ordinary conversation without assistive devices. It's a severe form of hearing impairment often caused by factors like congenital conditions, illness or injury.

Many cannot speak naturally as they are unable to hear the sounds that their own voice makes, which is a critical part of learning to talk.

But far from letting her condition stop her from living life to the fullest, 32-year-old Lim embraces her title as a Deaf photographer.

“Deaf” with an uppercase “D” is said to be used by individuals who identify with the community’s culture and shared experiences, while “deaf” describes hearing loss.

In 2015, a year before graduating from LASALLE College of the Arts, Lim founded her company issyshoots. She runs it with her mother Jacqui, who assists with interpreting among other tasks.

The 30-minute intimate portrait shoot on Thursday was designed to be just Lim and me, though – no interpreter, only her gestures and my feeble attempts at understanding.

Members of the public may also experience it firsthand on Dec 6, as part of the Enabling Lives Festival which brings together over 80 partners to champion disability inclusion.

Selected participants get to be portrait subjects, as I did, amid a roomful of quiet observers.

The experience hopes to encourage introspection and sensory engagement, as attendees immerse themselves in silence and Deaf culture – being seen by others and listening with their eyes.

While Lim could communicate via sign language, I, regrettably, do not understand it. I expected my limitations to greatly hinder our rapport.

But to her credit, it didn’t quite matter once I entered her world.

THE “SILENT STUDIO” EXPERIENCE

From the get-go, Lim seemed to share my cardinal rule of interviewing: Model the behaviour you want to draw out in others.

Easing into a high chair, I instinctively turned to my right. She appeared to register my preference for my left profile – and my nerves.

The proverbial "deafening silence" was causing a racket in my head: Where do I put my arm? Does my neck always sit like this? What’s up with my wonky eyes? And since when did breathing suddenly feel like advanced choreography?

Lim seemed to hear it all. Relax, she told me, by pressing her palms gently downward in the universal sign to loosen up. I dropped my shoulders, and she smiled.

I was a good student already, I thought, confident of my journalist’s ability to read body language. I got this.

Then she crossed her right arm over her left. I mimicked her, but she shook her head. The other way then? Left over right? Was she doing a mirror image? A riddle? A test?

Either way, we finally got the shot.

Come, hop off the chair, she beckoned next. She stepped behind it and placed her arms on the backrest.

Can you do that? Her expression read.

Maybe? After my previous communication hiccup, I wasn’t entirely convinced my brain could get my body to behave accordingly.

Lim valiantly, and very patiently, came to my rescue with a detailed demonstration. Stand just behind the chair, your stance open and steady. Rest your arms on the backrest, supporting your head. Tilt your head to the right, toward the studio lighting.

Next shot: Get back on the chair and cross your legs. Rest your arms across them. Wait – not like that, the other way.

Finally grasping my chronic left-right confusion, she gave me the kind of look that needs no words: I’m just going to touch your arm and move it myself. She gently reached for my arm, quelling my internal panic.

Honestly, thank goodness. There. Much better.

I felt my expression fading from exhaustion, but at least this prompted instructions I could execute: Smile, please! Lim drew her fingers across her mouth. On the count of three – smile. And on three, I beamed.

When it seemed she was done with me, she motioned to my colleague, who’d been tasked with capturing behind-the-scenes photos: Let’s get your photographer in the shot too.

Use your poses to represent your relationship, she typed on her laptop, and the text appeared on a projector screen. A smart move, given that we would’ve achieved nothing if she’d relied on hand gestures to explain that.

Easy enough. Our writer-art director relationship was built on me asking him to create the images to accompany my articles, and him having no choice but to agree.

We attempted a modest repertoire of poses, then it was a wrap.

Lim applauded enthusiastically, as though we’d been the stars. But really, it was she who shone.

FROM FEELING ISOLATED TO BEING INVOLVED

Communicating with people has always been a challenge, Lim later shared in a conversation facilitated by Singapore Sign Language interpreter Fang Shawn.

Growing up, she felt isolated and alone. She wanted to be part of the “hearing world”, she expressed, but hearing people usually don’t know how to approach the deaf.

I’d inadvertently been one of them mere minutes ago. I’d spoken to her interpreter, as he was able to respond verbally – only to be reminded I should address Lim directly.

My biases checked, I could start to understand the negotiations she’d been making her whole life.

In primary school, Lim discovered the magic of photography through her Deaf teacher, who was a hobbyist photographer. He enjoyed taking photos of the class engaged in activities, often sharing slideshows of his pictures.

“What I realised is there’s a power in visual storytelling, because through his eyes … he showed me that photos can tell a whole story. You can say your emotions. I didn’t know that I don’t need to speak, and photos can speak for me.”

One day during a family gathering, Lim picked up her mother’s camera, looked through the lens and realised she was “actually involved” in the event now.

“Photography allowed me to take photos of my family or friends, and that was the start of communication for me.”

After setting up her company issyshoots, she took on weddings, family portraits and event photography, among others, and stopped feeling left out.

Candid photos, in particular, are her favourite. The style allows her to “take photos on the fly”, without really having to communicate with the subject.

She can “speak invisibly”, she told me.

IN HER WORLD, ON HER TERMS

During our silent studio session, I heard Lim loud and clear.

By creating an environment for hearing people to experience Deaf culture, she simply wanted participants like me to learn to meet others at their pace. It was less about nailing the perfect photo and more about showing what Deaf people – or anyone with disabilities – can do, allowing participants to slow down and connect with them “in their own way”.

“Here, at the silent studio, the roles are reversed. I’ve become the host. It gives me the opportunity to direct and control the pace and dynamics of the shoot,” she shared.

“At events, weddings or family photoshoots, I’m always working on other people’s terms. But here, this is my culture. This is my way of communicating.”

As Lim moved gracefully around the studio, propping my arm up here, adjusting my stance there, I observed a woman born into a world of silence speak volumes through her presence.

The lack of noise sharpens her focus, she shared, helping her capture candid expressions while remaining acutely aware of everything happening around her.

That same clarity extends to her portraits. Her images are in black and white, which is an artistic choice – but has also allowed her to study a subject’s face and emotions without the distraction of colour.

Yet even with her heightened visual awareness, not being able to hear inevitably comes with its own challenges. Predicting what happens next at events, for instance, is an art form she spent 10 years mastering, even though occasionally missing an emcee’s announcements about last-minute changes still sparks more than a little inconvenience.

At one point, as if sensing that the balance between us had shifted after our portrait session, she asked, somewhat rhetorically: “Actually, it’s harder on all of you (hearing people), right?”

“I’m very used to silence. This is normal for me. But for you, you can hear all the movements. There’s so many sounds happening in this place; if I move a table, you might be distracted. But you’re supposed to keep calm. That’s your challenge.”

You assume you’re comfortable with silence after almost a decade of being a journalist, until you become an interviewee.

Suddenly you empathise with the reticent, who require more prodding than others. You even find yourself resonating with the occasional few who have the verbal range of a picture book, responding in a single word or grunt.

The absence of distraction somehow becomes its own distraction.

And yet, towards the end of my session with a Deaf photographer, I felt heard. The noise in my head finally settled, tapering off until it matched the quiet around me.

Register here for a silent studio session with Isabelle Lim on Dec 6, as part of the Enabling Lives Festival, which runs until Dec 7.

It will be held at the Enabling Village, located at 20 Lengkok Bahru.