She trains guide dogs in Singapore so blind people can get around independently and confidently

Christina Teng is Singapore’s only full-time certified guide dog mobility instructor. She trains and matches dogs to the blind and visually impaired, helping them gain independence, confidence and companionship.

Christina Teng is a guide dog mobility instructor who trains dogs to guide their visually impaired handlers safely around Singapore. (Photo: Christina Teng)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Christina Teng is an early riser. Some mornings, it’s for a quiet walk to ease her mind. Most of the time, though, she’s out with a guide dog, navigating footpaths, traffic lights, and MRT stations with it.

The 45-year-old is Singapore’s only full-time guide dog mobility instructor, and she is training these dogs to one day lead a blind person safely to where he or she needs to go.

One of those people is Manabu, who lost part of his vision after being diagnosed with a rare eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa. Before he got his guide dog, Momo, he would spend more than two hours travelling from his home in Yishun to his workplace in Jurong East.

The journey was long not because of the distance, Teng said. It was because with only a white cane to guide him, navigating crowds, escalators and unexpected obstacles was slow and exhausting.

With Momo, which Teng trained, Manabu now makes this daily commute in under an hour. He relies on his dog to guide him, reducing his mental and physical stress.

“That’s the kind of difference a guide dog can make,” Teng said.

The Singaporean has been with Guide Dogs Singapore since 2017. Soon after joining, she relocated to Melbourne, Australia, for two-and-a-half years of intensive training with Guide Dogs Victoria to be certified as a guide dog mobility instructor. She then returned home to train both dogs and their users, also known as handlers.

Before Teng, Guide Dogs Singapore, which was founded in 2006, had no local instructors. The charity relied on part-time trainers from overseas, often from Australia, who typically stayed for six months to a year.

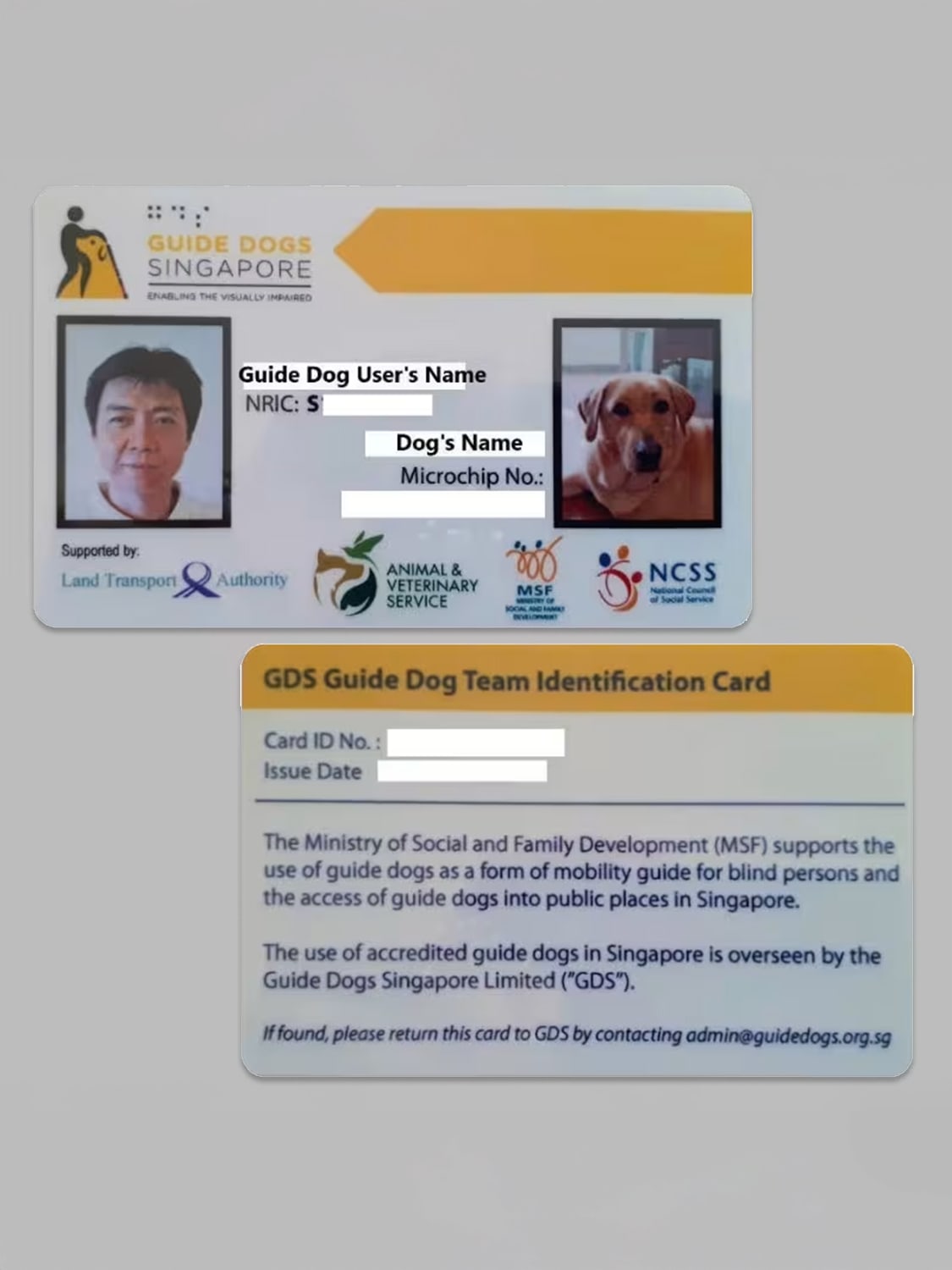

Since its inception, Guide Dogs Singapore has trained 14 guide dog teams, each consisting of a canine and its handler. Nine are currently active – Teng trained eight of them, including Singaporean paralympic swimmer Sophie Soon and her dog, Orinda.

IT STARTED WITH A LOVE FOR DOGS

Teng’s journey started decades ago with a library book she came across in primary school about guide dogs in the United States and the United Kingdom.

“I’ve always loved dogs, and I’ve always wanted to help people. So when I read about dogs helping the blind navigate the world, I was in awe,” she said, though she has no dogs of her own.

However, this was in the 1990s, and at the time, no similar organisation existed in Singapore.

“I shelved the dream,” she said. “I became a youth worker instead.”

After eight years in youth work, she left the workforce to become a stay-at-home mother to her two kids for a decade. But in 2015, Teng saw a news segment on television: Guide Dogs Singapore was looking for instructors – they wanted to expand and hire more locals for their programmes for the blind.

“My husband and I thought, eh, maybe it’s time to revisit that childhood dream,” she said.

Her application was accepted, and the family moved to Melbourne for her training. Her husband took unpaid leave from his work, and their two daughters, who were nine and seven then, followed along.

The programme was intense. It covered everything from handling dogs and knowing about different breeds to studying what mobility looks like for the blind, and experiencing what people with various types of vision impairments go through.

“Before we could even learn about what it’s like to train dogs, we first had to understand and empathise with the people we are serving: The blind,” she said.

“I had to walk obstacle courses while blindfolded, led by guide dogs, to understand what our future clients would experience. It was humbling.”

MATCHING THE DOG AND THE HANDLER

Not every blind person benefits from having a guide dog. “It’s about the person’s preferences, their environment, and how they move. Singapore’s landscape, with its narrower paths and complex MRT systems, can be tricky,” she said.

She explained that some blind individuals prefer to detect obstacles in advance and decide for themselves how to navigate them, making a white cane more suitable. Others may prioritise getting from Point A to Point B with minimal distractions or interruptions, and for them, a guide dog would be helpful.

“The cane is an obstacle detector – you find an obstacle and then react to it. Whereas the guide dog is an obstacle avoider – it anticipates and navigates around it,” she said. “The choice of mobility aid should always be about what empowers the individual.”

Every month, Guide Dogs Singapore receives around two or three enquiries from people interested in getting a guide dog.

“We follow up with an interview to know more about their visual condition, lifestyle, daily routes, living arrangements, and so on,” Teng said. “We assess everything to see if a guide dog would truly benefit them, or perhaps they may be better off with other mobility aids.”

Parents with children, she added, might find it challenging to care for a dog on top of their existing responsibilities, compared with those who live alone and might appreciate the dog’s company.

“These are lifestyle factors we take into consideration when we assess people’s suitability to be a guide dog owner,” Teng said.

The guide dogs come from Australia or Japan, where they are assessed for their suitability to be guide dogs. There, volunteer puppy raisers care for the canines, focusing on socialisation and basic obedience training.

The dogs are brought to Singapore when they’re about 12 to 14 months old. Here, Teng trains them for a further six months before pairing them with a handler.

The dogs are often Labrador retrievers or golden retrievers, which Teng said are ideal for their size, friendly demeanour, and the fact that they tend to be more welcomed in public spaces.

Guide Dogs Singapore does not own a kennel, so the trainee dogs stay in volunteers’ homes until they are ready to go to a handler. Teng is currently training one such dog.

Whenever Teng meets a new guide dog, she takes the time to get to know it.

“Like people, dogs have personalities too,” she said. “Some love navigating crowded train stations. Others prefer quieter neighbourhoods. It’s not just about skills, it’s also about preferences, personality and chemistry.”

Then, the matchmaking begins.

Teng arranges a “matching meeting” which lasts about two hours, where the potential handler meets the dog, goes on a short walk that lasts less than 30 minutes, and sees how they ‘feel’ together.

“It’s like a first date,” she laughed. “And I’m the matchmaker.”

If both dog and handler seem like a good fit, formal training begins. Teng works closely with the new pair for about a month to help them learn to move as one. They go through the handler’s common routes, including from home to the supermarket, hawker centre, bus interchange or MRT station, or hangout spots in their neighbourhood.

Even after the dogs “graduate” and a guide dog team is formed, Teng keeps in touch to check that the dogs are well cared for, that the handlers are happier with their canine companions, and to find out if they want the dogs trained for new routes so they can explore new places together.

“And if the handler moves to a new home or needs help navigating a new route, I will step in and train them again,” Teng said.

It’s like a first date, and I’m the matchmaker.

Providing one guide dog costs approximately S$45,000 to S$50,000, which includes training costs for both dog and handler. This is fully funded by Guide Dogs Singapore, and most of their funds come from public donations and grants.

The clients, however, still pay for the dog’s food and vet care, at a subsidised rate with Guide Dogs Singapore’s partners. The charity also offers complimentary grooming for guide dogs.

EMPOWERING THE BLIND IN SINGAPORE

“Nine active guide dog teams might seem like a small number, but the impact these dogs have on just one person’s life is immense,” Teng said.

Teng told CNA Women about another client who, after getting a guide dog, went on his first long solo walk in five or six years.

“Just being able to walk down two streets to buy his own groceries was a huge milestone,” she said. “It’s a small freedom most take for granted, but for him, it meant getting back the independence he lost when he lost his eyesight.”

Another client, who still has some residual vision, had trouble detecting changes at ground level. Stairs and ramps made her extremely anxious, and she used both a white cane and a walking stick to feel safe. Escalators were a no-go.

“She refused to take them,” Teng said. “But after six months with her guide dog, she asked me to train her on using escalators again. That was huge.

“She’s also the sole caregiver to her elderly father. With the guide dog, she now has the confidence to travel to his home on her own.”

Despite their positive impact, guide dogs and their handlers still face misunderstanding.

“Some people think the dogs are dirty and don’t belong in public spaces, or might bite,” Teng said. “But they’re not pets, nor are they aggressive. They’ve been trained as working dogs that are fit to go out in public, else they wouldn’t be suited to become guide dogs.

“Like police dogs, they serve an important job.”

She recalled a recent incident on the MRT. One of her clients had instructed her guide dog to “stop” before boarding the train. But a well-meaning commuter bent down and beckoned the dog to enter.

“The dog got confused and entered the train just as the doors were closing,” Teng said. “Because the handler is completely blind, she followed the dog. But the timing was off, and she tripped and ended up injuring her leg.”

The commuter who distracted the dog didn’t apologise, nor did they pause to help the woman after she fell.

“This is why it’s so important to give space to guide dogs and their handlers,” Teng stressed. “They need to focus, or it could be dangerous.”

DOS AND DON’TS WHEN YOU SEE A GUIDE DOG

1. Never distract a working guide dog

Doing so could put the handler’s safety at risk. It’s best to ignore the guide dog completely and let the guide dog team navigate on its own, unless they are clearly seeking help.

2. Do not feed a guide dog

A guide dog requires a balanced diet and is well-fed by its handler. Foreign food may disrupt this diet and cause problems for the guide dog team.

3. Avoid physical contact

Do not touch or pet the guide dog while it’s working, as this can cause disruption to the handler or distract the dog from its job.

4. Speak with the handler

If you’d like to help, speak directly with the guide dog handler and ask if they need assistance. Never tell a guide dog what to do or take the harness from a guide dog handler, as that can confuse the dog, which takes instructions from their user.

5. Avoid letting your pet interact with the guide dog

If you see a guide dog walking towards you, keep your pet on a short leash or carry it. This helps to prevent any potentially dangerous incidents between the guide dog and your pet. Do not offer any pet toys to the guide dog without asking for the handler’s permission first.

6. See guide dogs as working dogs, rather than pets

Guide dogs belong in public spaces. Unlike pet dogs, they are allowed on all public transportation, eating establishments, and places, including commercial buildings, hospitals, and schools.

According to Guide Dogs Singapore, there are no statistics on the number of blind people in Singapore. For an estimated number to guide their outreach and services, they refer to a 2019 study by the eye clinic Lang Eye Centre, which states that there are about 40,000 blind and visually-impaired people in Singapore.

“That’s a lot of people, and if guide dogs can make them all feel more independent, more confident, and less lonely, we want to work towards that,” Teng said.

As the charity grows, and after recently earning global recognition as a member of the International Guide Dog Federation, Teng is excited that she will soon no longer be the only Singaporean certified guide dog instructor.

By the end of the year, another trainee will graduate from the same course in Melbourne and join her in training guide dog teams in Singapore.

“As much as possible, we want blind individuals to feel empowered,” she said. “And if a guide dog is the right fit for them, we’ll do our best to make it happen.”

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg.