'Music is in my Orang Laut soul': She sings stories passed down through generations to celebrate her heritage

Growing up, Asnida Daud listened to many stories about Orang Laut life when she visited relatives in Pulau Sudong and the other southern islands. Today, she pays homage to her heritage by singing about islander life, preserving their memory.

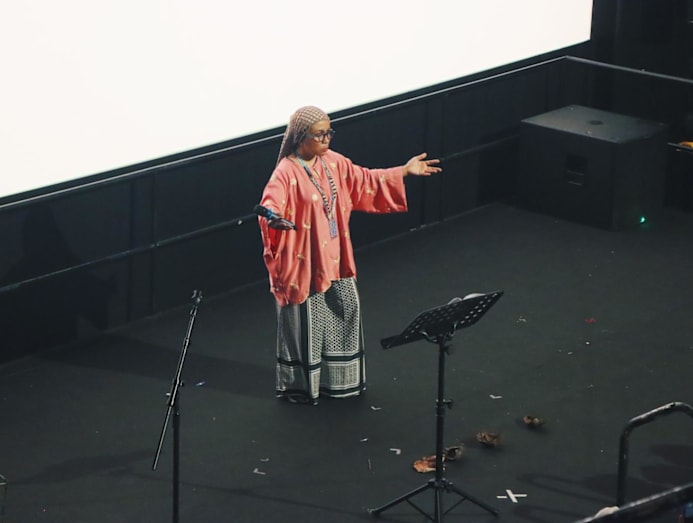

To Asnida Daud, music is a way for her to tell stories of almost-forgotten Orang Laut life. (Photo: CNA/Izza Haziqah)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Asnida Daud’s heart has always been with the sea.

As an Orang Laut, the indigenous islander population of Singapore, she spent a significant part of her childhood learning about her culture and heritage, which she’s grown to love.

This love comes through most potently in her music. Written in Malay, her songs are more than just songs. The 52-year-old calls them “aural histories” that carry the voices of her mother, aunts, and other relatives, and echo the folklore and lived experiences of her people.

Rapid urbanisation, economic shifts, and changing identities are threatening to erase the memory of her people, Asnida told me.

For her, music is the vessel that ensures those stories are not only remembered, but passed down, bringing to life the almost-forgotten world of the Orang Laut.

“As Orang Laut, a lot of our stories and experiences are often told orally and aurally,” said the mother of four adult children. “We didn’t often write our stories down because most of us just loved to sing, to speak, to tell – a lot of our liveliness comes from our songs and conversations.”

AN UPBRINGING OF MUSIC AND STORIES

“Dik, music is woven into my DNA,” Asnida grinned, calling me the shortened form of ‘adik’, which means little sister in Malay.

“My mother sang all the time. She taught people how to recite the Quran, the radio was always on, and my aunties and uncles also loved singing, dancing, and playing musical instruments,” she said. “My childhood was filled with music, and everyone around me sounded fantastic.”

She added: “When I read poems or almost any piece of writing, the words naturally fall into rhythm in my head. It’s a gift I don’t take for granted.”

Asnida’s relatives lived on Pulau Sudong (now a Singapore Armed Forces live-firing area), while her own family lived on the mainland. Her parents or grandparents would often take her and her two younger brothers to West Coast Park to catch a boat to the islands. Her late father called it “cari sedara”, or looking for relatives in Malay.

My childhood was filled with music, and everyone around me sounded fantastic.

Music and storytelling were a huge part of these visits. “My grandmother and aunties were storytellers. They told all kinds of tales about the people of the sea,” she said.

“I listened to ghost stories, love stories, how my parents met, how people’s grandparents were matched together, the way we dealt with rebellious teens, and the way kids splashed about in the water outside their home.”

Sometimes, the stories were sung, accompanied by flutes, gongs, and drums that seemed to be a fixture in every household Asnida visited.

Stories that warned children to stay out of the water during the rising tide could be a lullaby. The romance between a rich girl and a poor boy might become a song about the resilience of love. Even family gossip could be carried in a tune, framed with a “pembayang” – the preamble in a Malay poem – to deliver sharp meaning without causing hurt.

Against Asnida’s colourful, musical childhood in the 1970s and 1980s was a backdrop of many urban changes for Singapore.

On the mainland, local kampungs were being cleared to make way for urban housing. On Pulau Sudong and other islands, some Orang Laut families had begun moving to the mainland for work, school, and other reasons.

“I was a witness to all those changes,” she said. “Looking back, it must have been especially heavy for the Orang Laut elders who lived in their kampungs all their lives.”

By 1982, all the residents of Pulau Sudong had left. Many resettled in the West Coast area, near the park where they used to disembark from their boats when visiting the mainland.

Her family continued to visit relatives on other islands like Pulau Bukom, but even those trips became less frequent as people there moved to the mainland.

Asnida was then nine years old and even at that tender age, she recognised how precious the stories she grew up with were, as Orang Laut life slowly disappeared.

In the 2010s, something shifted. With Singapore’s 50th year of independence in 2015 and the bicentennial of British colonisation in 2019, came a growing interest in the diverse aspects of the country’s history, including the Orang Laut, Asnida said.

Academic researchers from local and regional universities began approaching her and other Orang Laut for insights into their lived experiences.

Then in her 40s and working at the education ministry, Asnida was jolted by this rising interest. “I didn’t think there could be so much interest in my people,” she said. “But when more researchers wanted to include our stories in books or archives, I realised I couldn’t just sing or approximate memories for fun anymore.

“I had to know the number of islands, the details of my and my neighbours’ family trees, and especially the meanings of poems and songs, the kind of music and dance we once had.”

EXPRESSING ORANG LAUT PRIDE THROUGH MUSIC

In her effort to give researchers an accurate account of Orang Laut life, Asnida began collaborating with others equally passionate about preserving their shared heritage.

Among them was Firdaus Sani, founder of Orang Laut SG, a platform launched in 2020 to document the stories of Singapore’s indigenous seafaring people. His grandparents hailed from Pulau Semakau, a southern island that’s now a landfill and ecological site.

Together, they went on “cari sedara” trips, this time to Bukit Merah, Telok Blangah, Kallang, and even as far as the Riau islands in Indonesia. They reconnected with distant relatives and gathered stories that might otherwise disappear.

Along with other mainland-born Orang Laut, Asnida recorded details of community life on the islands – the different islander subgroups, their homes on boats or stilt houses, and the types of vessels they used.

Over time, much of this material found its way into research projects and academic books. Contributing to that work was meaningful, but Asnida wanted to do more. This desire eventually led her back to music.

“Music is in my Orang Laut soul,” she said. “I want people to not just read about Orang Laut in books, but feel our lives and spirit in their souls.”

One of the first songs to embody this was Aok Diko, written in 2018.

The title, a colloquial call to “follow along”, was sparked by a tune her then 10-year-old son once played on the piano. Its childlike rhythm reminded her of a Malay word-link game she grew up playing, where each new word begins with the last syllable or word of the one before.

She wove that rhythm into lyrics that unfold like a chain: Tanah air, air laut, laut selat.

I want people to not just read about Orang Laut in books, but feel our lives and spirit in their souls.

The song tells the story of a young girl from mainland Singapore visiting her relatives in Pulau Sudong. It threads in the many tales she heard during her own childhood visits: How the islanders lived, what they endured, and the songs and refrains sung by her elders.

After Aok Diko came more songs. In 2023, she worked with Firdaus and the Esplanade on Air Da Tohor, a spoken performance exploring their elders’ stories through poetry, rhythm, and memory.

“Writing songs and performing the histories we inherited is about paying tribute,” she said. “But it’s also about telling our audiences: We’re here, we’re alive, we’re not forgotten, and our stories will always carry forward.”

Asnida has self-produced more than five original songs that chart her experience as an Orang Laut growing up on the mainland, and she hopes to compile them into an album. She also works with Orang Laut SG and other community platforms, from schools to advocacy groups, to share her heritage through song, poetry, and performance.

Asnida is also exploring ways to preserve the dance traditions of the Orang Laut.

“Did you know so many of us love to dance?” she asked. “The most natural expression of joy is to dance – and we love it so much.”

One favourite is the joget dangkung, a traditional Malay dance set to drums and gongs that tells stories of seafaring life.

Islanders would sail from place to place for it almost every other night. On bigger occasions, like weddings or graduations, the dancing could last all night, starting after the final evening prayer and ending just before the first call to dawn prayer the next day.

For Asnida, the joget dangkung is a homage to Orang Laut life, a reminder of community, resilience and joy, where everyone – relatives, friends, visitors – is welcome to join.

Now that there are only so few families still living on the islands around Singapore, the community rarely meets to dance – but, Asnida said, that doesn’t mean the spirit is gone.

“We still dance in our new homes, our HDB flats, our condominiums, our void decks, our multi-purpose halls, our function rooms,” she said.

This was on full display during Hari Orang Pulau in June this year, a day celebrating the islanders’ indigenous heritage. For more than two hours, people danced the joget dangkung in a field at West Coast Park. The dance floor was filled with people of all ages, ethnicities and nationalities.

The venue was a poetic choice. It was once where islanders docked their boats when they visited the mainland, and it sits close to the neighbourhoods where many Orang Laut now live.

That sense of openness and togetherness is what Asnida is striving to keep alive today.

“There are many ways to keep heritage alive,” she said. “Some people do it through food, some through classes, some with walking tours. For me, the best way is through music. It’s in my soul. It tells my stories. It keeps my Pulau Sudong and Orang Laut spirit alive.”

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg.