Feeling 'loose' after childbirth? The truth about postpartum vaginal laxity

CNA Women takes a closer look at different issues regarding postpartum health and wellbeing. First up: A guide to identifying and treating the postnatal condition that affects bladder control and sexual satisfaction.

Postpartum vaginal laxity needs to be properly identified and treated according to each woman's symptoms and expectations, experts say. (Photo: iStock)

If you’ve been experiencing urine leaks and unsatisfactory sex, and getting the feeling that you’ve become somewhat lax "down there" after giving birth, you may be suffering from post-pregnancy vaginal laxity.

Vaginal laxity or vaginal relaxation syndrome occurs when the vagina loses moisture and elasticity – a condition that is aggravated by childbirth and hormonal changes, according to Orchard Clinic, which specialises in postpartum recovery.

Co-founder Cheryl Han said hundreds of women visit Orchard Clinic each month with conditions such as urinary incontinence and dissatisfaction with intimacy, with the root cause being vaginal laxity.

How is vaginal laxity treated? First it needs to be determined, experts said.

“When women come to me saying ‘oh I’ve just had a baby and now I have laxity in my vagina’, I ask, ‘do you really?’,” said Laura O’Byrne, a specialist senior physiotherapist and co-founder at Health2U.

“Because the first thing we need to address is, what is your vagina? Most women refer to everything down there as their vagina when actually that’s not the case,” she added.

“Many women will tell you they don’t know what their vulva looks like because they’ve never really properly looked. It’s a part of them they never really see. We should be encouraging a healthy form of self-examination.”

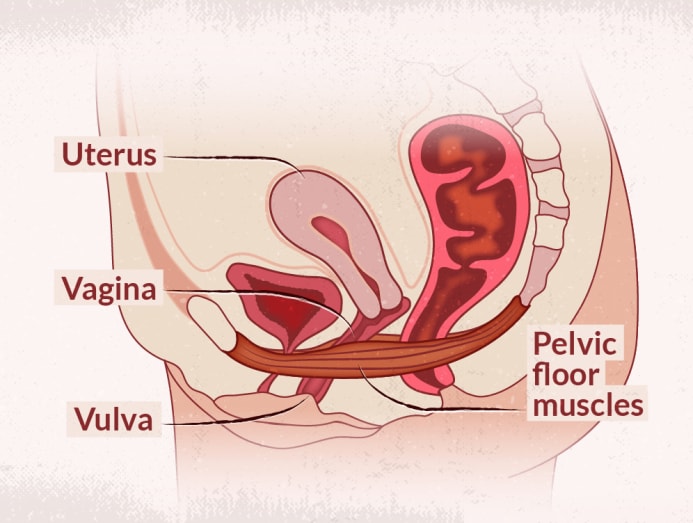

To prove her point, during a Zoom call with CNA Women, O’Byrne took out a model of a woman’s anatomy and pointed out the parts that typically cause problems for a woman after childbirth.

The first is the vulva, the outer part of a female’s genitals – what O’Byrne described as “everything on the outside”. The vagina, she said, is a tube inside the body that connects the vulva to the uterus. All these organs are contained in the pelvic area and are supported by muscles that sit on the pelvic floor.

Another way is to look at the vagina as “simply a column, a canal”, said Dr Jessherin Sidhu, a general practitioner who specialises in women’s sexual health. “That canal is supported by structures around it, like the scaffolding that holds up a building. That scaffolding is the pelvic floor.”

WHAT IS VAGINAL LAXITY?

For postpartum women, the walls of the vagina may become lax due to the trauma that pregnancy places on the pelvic floor or the excessive stretching of vaginal tissue through vaginal birth, said Orchard Clinic’s Han.

Women who have never given birth may also experience vaginal laxity.

Post-menopausal women may suffer from vaginal laxity due to hormonal changes associated with ageing, said Han. Even younger women may experience vaginal laxity if they have a weak pelvic floor.

“You can have pelvic floor issues at any stage. You can have it not after having a baby, you have it at a young age, at an old age … You can have pelvic floor issues as a man as well. There’s no discrimination here,” said O’Byrne.

“Changes in the pelvic floor can cause appreciation of laxity. As the support structures start to wear away, that column feels like it’s not held up properly, not closed in properly,” said Dr Sidhu, who runs InSync Medical clinic.

Vaginal laxity typically causes problems such as urinary incontinence and unsatisfactory sex, which may manifest as a loss of sensation during intercourse or painful penetration due to dryness, experts said.

“Normally when women come through it starts with dissatisfaction with penetration,” said Dr Sidhu. “We often hear this classic statement: ‘I feel very loose, like I can’t tighten. Whenever I have intercourse, I feel like I have to purposely grip around my husband’s penis.’”

Others may complain of urine leakage whenever they laugh or cough, or when they are engaged in high-impact activities such as jogging, she added.

“Sometimes they’ll tell me it’s dry when they’re walking, like tissues are rubbing against each other,” said Dr Sidhu.

According to Dr Sidhu, sometimes women don’t complain about a direct symptom of laxity, but an indirect one such as frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

“When you’re perpetually dry, you’ve lost this defence barrier … And dry tissues allow bugs to get in quicker, thus increasing the risk of infections.

“Typically, when women are getting more UTIs and you probe further, they might tell you they’re not satisfied with penetration too. Often dryness can be painful so they don’t even commit to a full penetration. And if penetration can happen painlessly, they’ve lost sensation,” she said.

It is worth noting that postpartum problems share common symptoms and so, what you may think is vaginal laxity could easily be something else.

A good rule of thumb is that a simple problem of vaginal laxity “should only present certain inconveniences such as irritation or abrasion” when you’re going about your day-to-day activities or even during sex, said Orchard Clinic’s Han.

WHEN IS IT NOT VAGINAL LAXITY?

If your concern is how lax or saggy it looks around your vaginal opening, the problem you’re looking to solve may not be vaginal laxity, but laxity of the labia, which comprises the folds of skin (or lips) on your vulva.

“Typically, when women come to me after giving birth, they think it’s the vagina they’re concerned about, but it’s actually the vulva that has changed,” said O’Byrne, who was formerly a physiotherapist with Jurong Health.

“If you look down and your labia is stretched out, then it’s a labia laxity issue,” she added.

O’Byrne classifies labia laxity as an aesthetic issue – something that physiotherapists typically do not deal with. Women who have this concern may seek the help of plastic surgeons specialising in procedures such as labiaplasty.

If you’re feeling a sense of heaviness or pressure internally, it could be the sign of a prolapse, said Han.

A prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor is so weakened, often due to the strain of vaginal birth, that it can no longer support internal organs such as the bladder or the uterus. These may then slip out of their normal position and cause persistent discomfort. In severe cases, they may protrude into the vagina and even slip out the vulva.

DIAGNOSING THE CONDITION

Experts shared that for women who suspect they may have vaginal laxity, it is best to see a pelvic floor physiotherapist or a women’s health specialist.

“You wouldn’t go to a pelvic floor physiotherapist if you were giving birth to a baby, so don’t go to a gynaecologist to rehab your pelvic floor – that’s not what their specialty is,” said O’Byrne.

If you do consult a gynaecologist, chances are you will be referred to a physiotherapist for rehab.

“Hospitals like KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital do have a department of women’s health physiotherapists … They’re not your regular physiotherapists, focusing on sports medicine. They really focus entirely on pelvic floor muscles. It’s a sub-specialty,” said Dr Sidhu.

A consultation with a specialist GP or physiotherapist will typically begin with questions about a client’s lifestyle:

- Age and experience in significant milestones such as pregnancy

- What type of delivery did you have — vaginal or Caesarean?

- Have you had any surgeries in the pelvic area?

- What is your daily routine like?

- How much time do you spend sitting?

- How often do you exercise?

- How often do you pee in a day?

- What kind of job do you have? Is it the kind of job that forces you to put off relieving yourself until the end of your working hours?

- What medication are you taking, including hormones?

- Have you had pelvic floor physiotherapy?

The conversation may then move towards those pertaining to bodily functions:

- Can you control your bladder? Are you leaking urine?

- Are you getting pain from penetration?

- Are you having pains around your vulva?

- Can you control your bowel movements?

- Can you control your flatulence?

There may also be physical examinations.

Dr Sidhu said she would first conduct an external check, and not exclusively to the lower region.

“We look for elements of things like dryness elsewhere because women with menopause will complain of irritability and dryness in other areas. When we do focus on (the lower) area of the body, we look for dryness in the vulva,” she said.

“We also look for shrinkage of tissues. Sometimes, that area in a younger person is supposed to look very supple – there are nice folds and ridges here and there – and there’s a level of hydration.

“But when you look at someone who’s suffered tissue ageing in the vulva, you see that the tissues are really quite dry in appearance. They might have red dots there and they might not have the elasticity,” she added.

An internal check might involve a speculum, a tool also used in Pap smears.

“Again, on the inside, you might see similar things like a loss of these nice little folds. They seem more flattened out, the tissues are thicker and there’s a lack of hydration. You’re not looking for how much liquid there is in the canal – that’s not hydration. Hydration is what the tissues look like, the walls,” Dr Sidhu added.

Doctors may also use modalities like ultrasound scans to gauge the strength of a patient’s pelvic floor.

“When you breathe in, the dynamics of your muscles change – your diaphragm moves up and down. At different times of your breathing, they look at how this ring of muscles around your vagina moves. “Sometimes you see a lack of movement in this ring and you may go ‘ah, the muscles there are a little weak – they’re not moving and contracting the way they should’. From here you can deduce that the muscles are weak or very tight,” she said.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

“Unfortunately, for a long time we’ve just told women ‘oh, you’ve had a baby, it’s normal to leak’. That’s not the case at all. We should not be saying ‘oh it’s normal, you’re okay’. We should be saying ‘no, we need to address that’. There’s lots of things we can do about (your condition), we can address it appropriately,” she said.

“A good and strong pelvic floor is something we should all have.”

Physiotherapists like O’Byrne will typically recommend a rehabilitation programme.

“In France, after giving birth, women expect to see a pelvic floor therapist 10 times. As far as they are concerned, we need to rehab and fix everything that just went through all the trauma of giving birth. It’s a full contact sport - no one comes out unscathed,” she said.

Through a rehabilitation programme overseen by a physiotherapist, a woman can correctly understand her anatomy, identify the cause of the laxity and obtain guidance in restoring the functions related to the condition, O’Byrne explained.

We need to rehab and fix everything that just went through all the trauma of giving birth. It’s a full contact sport – no one comes out unscathed.

If a patient is diagnosed with weak pelvic muscles, a therapist may recommend kegel exercises. The pelvic muscle-strengthening exercise popularised by American gynaecologist Arnold Kegel must be properly prescribed and taught.

“When you tell someone to do 300 kegels, first of all, some women don’t know what that is. Also, telling someone to just go and do 300 kegels is a waste of the person’s life. You need to make treatment specific to the person.

“For example, you need to first check that her muscles are weak and not overactive. Because if they are overactive, she should stop doing pelvic floor squeezes and instead relax them down first,” said O’Byrne.

Relaxing an overactive pelvic floor involves “down training”, a muscle relaxation method that may include diaphragmatic breathing and body scanning.

“This is where we get the muscles to ‘learn to relax and let go’,” said O’Byrne. “It’s usually more challenging than strengthening someone up as it’s usually easier to learn to contract a muscle than it is to relax it.”

So how long does it take before you get results from rehab? O’Byrne said it depends on the severity of your issues.

“With some women it can be as simple as one or two sessions for a straightforward issue like minor pelvic floor weakness, which can be corrected with exercise. With more complex cases such as fourth-degree tears and pain, there is usually some improvement after a few sessions but it can take a few months to see significant change,” she said.

A pelvic floor assessment with a physiotherapist costs around S$190 at the Health2U clinic, and clients typically come for a session once a week or every two weeks, said O’Byrne. A rehab package, which includes five face-to-face consultations and access to the clinic's eight-week online programme comprising workout videos and a private Facebook group, can set you back around S$650.

Many clinics, such as Orchard Clinic, supplement muscle rehabilitation with electromagnetic or radiofrequency therapy.

“Radiofrequency works to tighten the inner walls of the vaginal canal and improve skin texture of the labia or outer lips of the vagina, while electromagnetic therapy works to strengthen the pelvic floor,” said Han, adding that such treatments can range between S$300 and S$1,200.

One treatment uses what is called the Emsella HIFEM technology to relieve issues such as urinary incontinence caused by weak pelvic floor muscles. Patients sit in a chair during the session and it harnesses electromagnetic energy to simulate thousands of muscle contractions, hence "re-educating the muscles and creating greater muscle memory", according to the clinic.

About 70 per cent of Orchard Clinic’s clients see positive results by the first month and 90 per cent experience results by the sixth, said Han. Positive results include increased vaginal tightening, improved urinary incontinence and intimate satisfaction.

InSync Medical’s laser therapy treatment, FemiLift, involves a probe being inserted into the vaginal canal and made to spin around.

The vaporiser inflicts “micro injuries” on the vaginal wall, signalling to the body that it needs to heal the tissue that has been scarred, said Dr Sidhu.

“When you ablate tissues like that, you’re giving your body an accelerated signal, telling it to go and heal the tissue properly. You force healing on that part of the vagina that otherwise would not happen,” she said.

FemiLift is also said to promote collagen production, which in turn boosts hydration in the vaginal walls and leads to tightening of the canal. This helps to solve a host of postpartum issues including dryness, recurrent infection, urinary incontinence and “looseness”.

Laser therapy is, however, still an invasive procedure, but Dr Sidhu assured it is “quite safe in the right hands”.

“Heat therapy forces and promotes tissue growth and tissue healing, so we’re accelerating that process by applying controlled micro injury to that area of the vagina. This is something that’s been done on the face all the time.

“What you need is a professional that knows about the settings and which modalities to use on you … As it is a minimally invasive procedure, there is a small amount of risk. And how do you know that the risk is appropriate for you? Find a physician trained in this department, someone who has used lasers a lot,” she said.

FemiLift takes 10 minutes per session, with InSync Medical requiring clients to attend at least three sessions a month. A package of three sessions as well as a follow-up session 12 months after the procedure costs S$4,500.

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg (CNAWomen[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg).