The Big Read: The pandemic has affected the human psyche. What does this mean for Generation COVID’s future?

The “crisis of a generation”, as the pandemic has been called, has left an indelible mark on the psyche of many youths, potentially affecting their mental wellness and social outlook. (Illustration: TODAY/Anam Musta'ein)

- A recent TODAY Youth Survey 2021 found a majority of those aged between 18 and 35 saying they have become less sociable, and more cautious and fearful

- The finding which showed that the pandemic has led to greater insecurities among youths echoes that of polls elsewhere

- Youths interviewed also spoke about their struggles amid reduced social interactions at school and the workplace, their hopes and concerns about the future, and how the pandemic has led to a recalibration of their plans and priorities

- COVID-19’s economic and health impact on Singapore so far has been relatively less severe compared to several other countries

- Some experts noted that the jury is still out on the actual longer term impact of the pandemic on an entire generation in Singapore

SINGAPORE: Before the pandemic, Mr Nicolas Mok, 25, thought that his first job out of university would probably be an investment banker or a fund manager.

But the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School graduate, who began his job search during his final year of studies last year, had to go back to the drawing board after the COVID-19 crisis scuttled his plans.

With businesses freezing headcounts and the competition tightening around the limited vacancies for highly sought-after finance jobs, Mr Mok decided to take a chance in starting out his own business during the pandemic.

To his mind, it is better to take the plunge now when he is young and seize whatever opportunities may come amid the crisis, than to settle for a job that he may not enjoy while being exposed to the risks of pay cuts or lay-offs.

“(With COVID-19) everything is so unpredictable, I thought I’d just take the chance and do something that I like ... You never know, right?,” said the co-founder of Belly Empire, which helps local food businesses streamline and expand their operations.

The same set of circumstances that many are facing as the pandemic rages can, however, trigger contrasting responses: At the other end of the spectrum, the COVID-19 crisis has caused other young Singaporeans to set aside their dreams and ambitions in favour of a more pragmatic path.

Mr Andy Lim, 32, decided to stay on in his current job as a communications professional in a public relations firm, even though he was considering a mid-career switch before the pandemic struck, perhaps even starting his own home-based food business or working abroad for a year or two.

“I think COVID has kind of blurred what was possible. When you’re young, you feel there are many possibilities you want to explore but right now, I would like to play it safe,” said Mr Lim, adding that he does not see himself as a risk-taker.

The stark contrast between Mr Mok and Mr Lim reveals the different approaches of risk-taking and risk-averse millennials, whose career and life decisions must now contend with a coronavirus pandemic that has upended plans and created uncertainties as to what the future holds.

Both are part of what some have termed Generation COVID, a loose moniker covering people from late childhood to early adulthood who are coming of age during the health crisis.

The “crisis of a generation”, as the pandemic has been called, has also left an indelible mark on the psyche of many youths, potentially affecting their mental wellness and social outlook.

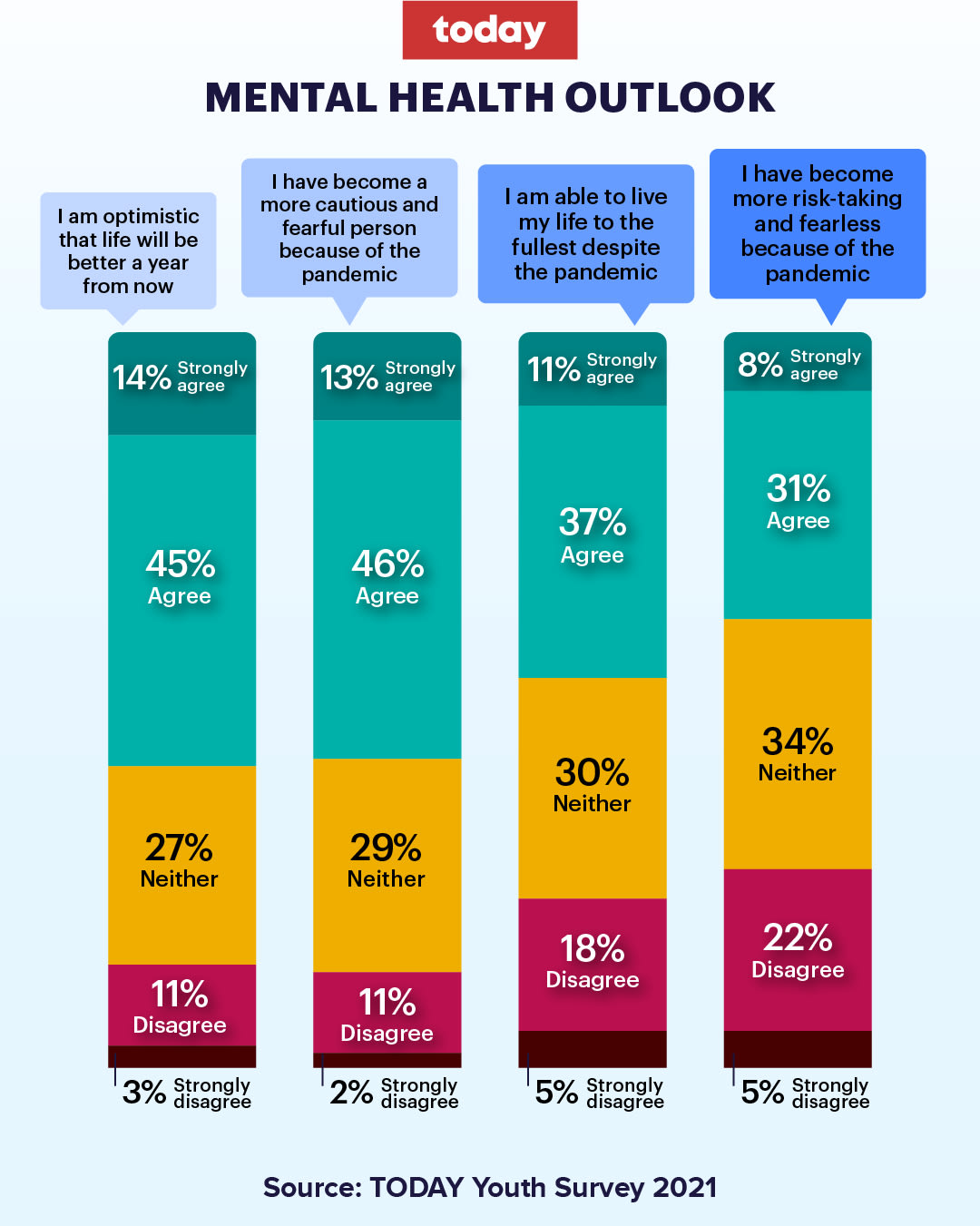

The TODAY Youth Survey 2021, which polled 1,066 respondents between the ages of 18 and 35 in early October, found that the pandemic has caused many young people to become more insecure about their future in general.

About 59 per cent of the respondents said they have become more cautious and fearful, compared with a smaller 39 per cent who have become more risk-taking and fearless.

Less than half (48 per cent) said they are able to live their lives to the fullest despite the pandemic. About 23 per cent disagreed with the statement.

Meanwhile, more than half (54 per cent) said they have become less sociable compared with before the pandemic.

The TODAY Youth Survey 2021 finding which showed that the pandemic has led to greater insecurities among youths echoes that of polls elsewhere.

In April, a global survey of 17 countries by the British publication Financial Times of under-35s revealed that young people around the world were feeling increasingly insecure about their futures amid the pandemic.

It found that significant proportions (more than 40 per cent) of respondents believed that they would be worse off than their parents in holding secure jobs, having enough money to live well, owning their home and living comfortably in retirement.

All these insecurities and pessimism among youths are concerning, especially since the impact of the COVID-19 crisis could persist for a while, according to sociologists, psychologists and youth experts interviewed.

Sociologist Paulin Tay Straughan from the Singapore Management University said that the most pressing issue is social inequalities that have been sharpened by the pandemic, since those with lower socioeconomic statuses may find greater difficulty transitioning to a post-pandemic normal than the rest of the country.

“Each time we talk about being able to take advantage of emerging opportunities (in this pandemic), we must also realise that not everyone can access the same kind of opportunities as those in privileged positions,” said Professor Straughan, who is also the dean of students at Singapore Management University.

But the jury is still out on the actual longer term impact of the pandemic on an entire generation in Singapore, noted some academics.

After all, COVID-19’s economic and health impact on Singapore so far has been relatively less severe compared to several other countries.

In April, when Singapore was dealing with fewer than 50 COVID-19 new cases daily, the Financial Times poll found that Singaporeans were the most confident about their outlook out of the 17 countries polled, in terms of the proportion of respondents who felt they would do worse than their parents.

However, in the last three months or so, Singapore has been hit by a wave of infections caused by the Delta variant, with daily cases surging to several thousands.

“(What the country faces is) whether the next generation of Singaporeans feel empowered or not, as opposed to whether they have really been deprived of (opportunities),” said Associate Professor Leong Chan-Hoong from the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS). “It is a generational crisis of confidence.”

And as isolation measures lead to a rise in depression and anxiety among youths, there could also be longer-term scars on the mental health front that will continue to reverberate for years to come.

Ms Anthea Indira Ong, former Nominated Member of Parliament and an advocate of mental wellness, said that if not cared for, the longer-term social development of youths could also be affected.

If youths do not have an optimistic view of the world, their despair and anxieties over job insecurity and their sense of self will affect the way they develop themselves. These will also have an impact on whether they find it possible to fulfill their dreams and potential, said Ms Ong.

The pandemic, depending on how long the measures needed to contain it last, may also entrench a changed normal of social interactions that can later show up in relationships and family life, she added.

For some insights into the psyche of Singapore’s millennials and Generation Zers as they grapple with the still-unfolding fallout of the COVID-19 crisis, TODAY looks at how past crises have impacted previous generations, and speaks to youths to find out how they are faring and their perspectives of what the future holds for them.

LOOKING BACK AT PAST CRISES

The long-term impact of past financial crises and wars on generations of people is well-documented, especially for the cohort whose coming of age coincides with such precarious periods in time, experts said.

Assoc Prof Leong noted how a number of published research on the impact of the financial crisis of 2008 had shown how the loss of permanent jobs and meaningful work experience for people starting out in the workforce could snowball into other issues a decade later.

In 2018, the International Monetary Fund conducted a study measuring the decline in economic activity in the decade after the collapse of the Lehman Brothers, and found that income inequality, fertility rates and migration had declined over the years in several advanced economies, and these would continue to be a drag on labour force growth. formal studies exist.

What mitigated these factors were the individual country’s policies during and after the crisis to bolster the economy during the global financial panic, the study noted.

Assoc Prof Leong said: “If people get caught up in that sort of generational deprivation, they end up languishing in terms of career and employment. They end up doing part-time jobs or entering the gig economy, and even if the economy picks up, they may not be in time to follow suit as opposed to a fresh graduate entering the workforce during the years of economic recovery.”

World War II also provides a well-studied example of how populations react to an unfolding crisis, experts said.

In the United States, the 1939 to 1945 conflict, which killed 75 million people worldwide, created an entire generation of people which Time magazine called the Silent Generation, or Silents. The Pew Research Centre defined them as those born between 1928 and 1945.

The Silents were portrayed as conformist and civic-minded, preferring to play it safe rather than rock the boat.

But the generation following it, the post-war baby boomers, would experience a markedly different economic trajectory compared with the Silents, led by a sense of confidence that WWII would mark the end of hostilities and usher in an era of safety and prosperity.

In comparison, pandemics in history are less remembered and studied than war.

Some sociologists and historians believe the 1918 to 1919 Spanish flu outbreak, the last great pandemic that was estimated to have infected more than 500 million people and killed 50 million globally, is believed to have led to long-term socioeconomic disparities and a reckoning of people’s commonly held beliefs, though few

To date, the COVID-19 pandemic, which broke out in late 2019, has infected more than 250 million people and killed over five million around the world.

Dr Annabelle Chow, a clinical psychologist who runs her own practice Annabelle Psychology, said she has seen many patients open up about their frustrations and anxieties, including frontline healthcare workers who are experiencing burnout.

She cannot help but think about how her elderly grandmother’s outlook on life was shaped by the latter’s experience during the Japanese Occupation, and later from witnessing the violent racial conflicts of independent Singapore’s early years.

“The way she approaches life and thinks about it and deals with stress is just very different from me,” said Dr Chow, who is in her 30s.

“In the end, there will be two groups of people that come out from any crisis: those who succumb to the pressures and stresses, which then becomes a big struggle for them to stand up again. And at the other end, there are those who can rise up and become more resilient.”

Why are workers still languishing after almost two years of work-from-home? And do office workers have a "right to disconnect"? HR experts discuss on CNA's Heart of Matter podcast:

COVID-19’S IMPACT ON PSYCHE OF YOUTHS

Unlike preceding generations, millennials and Generation Z live in a different era of digital connectedness and opportunities, but could be feeling the pinch of growing economic inequality due to the pandemic, said experts.

Around 10 young adults aged 17 to 35 spoke about their current struggles amid reduced social interactions at school and the workplace, their hopes and concerns about the future, and how the pandemic has led to a recalibration of their plans and priorities.

In general, their most common source of anxiety is job insecurity, which has affected their appetite for risk and desire to pursue their dreams and ambitions. They also pointed out how money, especially cash at hand, has become especially important in a crisis situation.

Mr Lim, the communications professional, who used to have an “entertainment budget” before the pandemic and would not think twice about spending money on the latest Nintendo Switch games every month, said he has not done so since last year.

“Saving money is much more important. I’m afraid I might lose my job.

"I can’t have the ‘you only live once’ mindset because I’m still going to live. Living has things like bills to pay and maybe houses to buy,” he said.

Procurement specialist KJ Tay, 31, who is married with a son born last year, said that before the pandemic, he was thinking of switching to another industry.

The sight of long lines for government support at community centres last year scared him, and he no longer contemplated a job change.

“COVID-19 has taught me that staying in one place is a form of security that not everyone has,” he said.

NUS sociologist Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser said that while the well-to-do can afford to venture out of their comfort zones, it is likely that those able to “hold on to a middle-class life in Singapore” would have a lower risk appetite.

Meanwhile, those who have lost their income or jobs may actually end up assuming even more risk when they are forced to take on freelancing jobs or even jobs in the gig economy, which are more precarious due to their transient nature and the lack of employee benefits.

“Overall, there would be a mindset change away from settling into stable careers as well-paid employees. Instead of aiming to live the ‘good’ life, many may settle for a ‘good enough’ life. I suspect that family formation may become less of a priority, with cohabitation and having no children becoming the norm,” said Assoc Prof Tan.

BREAKING THE MOULD

While some prefer to hunker down until some semblance of normality returns, there are those, such as Ms Divya Subramaniam, who see the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to break the mould.

In May, the 25-year-old moved to the Indonesian island of Bali on a whim.

“It was a Sunday that my friend suggested we go to Bali and we got on a flight that Friday. Of course I was thinking, should I or should I not? I had never taken any big crazy risks like that.

“But I wanted a change in scenery. I felt I was not growing (in Singapore),” said Ms Divya. Earlier in the pandemic, she had found a job working remotely for a United States tech company. She kept the job after moving to Bali.

She had to fork out S$2,000 to S$3,000 to get to Bali, and did wonder if the risk would be worth it. Ultimately, it was, she said.

“If not for COVID-19, I wouldn't have found that remote job. I would have probably been working in Singapore. Now I know I want to be able to have the freedom to go anywhere,” said Ms Divya, who left Bali for the US in September to meet her boyfriend whom she met online.

Ms Suhaila Shaikh-McCann, 28, said that COVID-19 has definitely made her more spontaneous and has taught her to live in the moment a little bit more.

“Before, I was always just stressing about the future. Constantly budgeting and thinking about what's next.”

“(Now) I'm not worried about (the future) as much because you just don't know what's gonna happen,” said Ms Suhaila who currently works in marketing.

She added: “I have had friends who succumbed to COVID-19, one of them in South Africa and another one in England. Seeing that happening to young, fit people … definitely made me a little bit more like, I want to buy something nice? Sure, go for it.”

For 27-year-old Sabith Zarook, being cooped up at home made him realise that he has yet to see what the rest of the world has to offer.

As such, he is now seeking more “spontaneous actions”.

Mr Zarook, who works as an analyst at a start-up, said that he now sees value in moving overseas, something he was not keen on doing before.

“This job I’m doing is (different) from what I studied in school, which was accounting. I didn’t like what I was studying, so I thought I’d take a leap.

“COVID-19 has solidified my thinking in taking such leaps, reaffirming me that I need to go and get out and explore more. I need to try something new,” he said.

CHANGE IN PRIORITIES

Ms Suhaila said that pre-COVID-19, work was the “most important thing of my life” and admitted that she would put her career ahead of her family.

“I still have a five-year plan of what I want to achieve professionally but I think COVID-19 has really helped me refocus on what's important,” said Ms Suhaila, who lost her job with a technology multinational company in April last year.

“I really had an awakening at that time (in April) to understand that the most important thing right now is my family. So we were just spending lots of time together and it was just the most beautiful thing,” she said.

Ms Ong, the mental health advocate, said that from her interactions with youths, she got the sense that the pandemic has led to a renewed reckoning about what really matters to them.

“The pandemic has really called up a lot of this questioning of the ‘why’, because, well, you can die tomorrow, and some of them have been putting it very bluntly to me that (the threat of death) has never been so real, so close and so clear,” she said.

In the US, some young adults have converted their side hustles into their main jobs, or focused on self-actualising goals that would otherwise have been on the backburner. The New York Times has called this phenomenon “the YOLO Economy”. YOLO stands for You Only Live Once, a mentality that one should live life to its fullest extent, even if that means taking on risks.

Ms Ong said it is a different situation for Singapore youths, who are not exactly living life with reckless abandon as the YOLO mantra suggests.

“They are not jumping off cliffs, maxing out their credit cards and all. It is more of the deep sense of existentialism that’s actually more practical — do they want to just go get a job that they know they are not going to enjoy, and may even lose?

“So, it is this sense of more thoughtful deliberation of the choices that youths need to make that I am hearing from a lot of young people,” she said.

ISOLATION AND ITS EFFECTS

While much of the pandemic’s impact on the psyche varies from person to person, its mental health effects — arising from the tightened measures to curb the virus spread — tend to be similar for most people.

One survey last month found that nearly seven in 10 Singaporeans said 2021 was their most stressful year at work, with 58 per cent struggling more with mental health in the workplace this year than in 2020.

For youths, they too are feeling the pressure of restrictions in school and at home.

Student Meghana Prasad, 24, said she began to “feel suffocated” in Singapore when she saw her friends in Europe, the US, Canada and Australia living much more “normal lives as compared to us” — such going to concerts — on social media.

This has also led to Ms Meghana feeling “socially isolated”, when she sees that her extended family in India are able to meet often.

“It has definitely impacted my mental health, and I’m desperate for an escape physically and mentally. I’m still coping but I don't know how long I can hold up,” she said.

Besides the inability to travel, experts said the effect of social isolation at workplaces and in schools could be even more profound.

Assistant Professor Cheung Hoi Shan from Yale-NUS College, who researches parenting and child development, said that the curtailment of social interactions in schools from an early age, for example, could have an impact.

“We’re talking about how kids may grow up, maybe not knowing what it feels like to be in a school camp with 50 people.”

But saying that the past two years of the pandemic will alter the personalities of millennials and Gen Zers is still a stretch, she noted.

“In the whole grand scheme of things, it has been two years of restrictions out of a longer history of life experiences and people relationships, which can be quite resilient. One crisis is not going to wipe out all the experience and learned behaviours that have been built since the day we were born,” said Dr Cheung.

Instead, experts are more concerned about the transient impact of stress and anxiety.

One example is the circuit breaker period last year, whereby the sense of isolation could also be compounded by existing familial stresses, such as work pressures faced by parents, said Dr Cheung.

“Typically, your relationship with your peers or with your teacher can act as a buffer, which was missing for this group of people during a home isolation period. It is the sense that, you know, my parents are not doing well, and my parents are screaming at me all the time. And I have nobody to turn to,” she said.

Dr Chow, the clinical psychologist, has observed an uptick in the cases at her clinic of people who feel anxious over the prolonged sense of isolation and the greater obstacles to socially interacting with groups of friends.

“It is also very pronounced how suddenly people are saying that they do not know how to interact with other people anymore in a healthy way,” she said.

It can also be a constant struggle for young adults who are just entering the workforce at a socially distanced era to find meaning and identity in their work, added Prof Straughan.

“They are inducted through an online welcome and then after that end up working on their own, and at most receiving a call from their supervisor to do this and that,” she said.

“Without the office space interactions, or even just going out for coffee together, and talking about aspirations, managing office politics or demands, they end up being very much alone.”

THE NEXT GENERATION

The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is not going to be the last crisis in the lifetime of millennials and Gen Zers, who also have to contend with an ever-growing climate crisis and the likelihood of another pandemic, said those interviewed.

Hence, developing resilience against crisis is a must, they said.

“I would say I’m pretty determined to adapt to COVID-19 and get used to a new normal. It was hard at the beginning, but I can feel myself getting more resilient,” said first-year junior college student Delfine Yew, 17.

“I think if I view these changes as challenges that I have to conquer on my road to success, then I'll be more optimistic for the days ahead.”

With millennials, who are in their 20s and 30s, they have at least an early point of reference in their lives, where they can still remember pre-pandemic social norms and may also have established long-lasting friendships and support systems, said the youth experts.

But it may be a different story for the future generation who will be born during or in between crises.

Already, paediatricians and psychologists globally have expressed concerns that toddlers are experiencing increasing bouts of stranger anxiety — the fear that babies feel when interacting with unknown people.

Young children are also feeling signs of separation anxiety when they return to schools after periods of social isolation, according to reports from Canada.

If the effects of the current pandemic are prolonged, Assoc Prof Tan said it could lead to more pronounced anxiety about the future for this group when they come of age.

“They might have serious doubts about whether the success formula used by their parents or grandparents would still work for them, whether they could ever achieve income and job security, let alone experience upward social mobility, and live a middle-class existence,” he said.

Dr Tania Nagpaul, a senior lecturer at the SR Nathan School of Human Development at SUSS, said the most telling impact of the pandemic will be on the new Generation Alphas, born between 2010 and 2024 and are currently pupils in primary school.

They have been insulated from the uncertainties that COVID-19 has brought, mainly having to embrace home-based learning temporarily, but are not forced to make important decisions or kick-start their fledgling careers at an inopportune time.

“Their hope is that the coming years will be COVID-free and life will revert back to normalcy,” said Dr Nagpaul.

Whether life would be COVID-free by then remains to be seen, but Prof Straughan said she believes that youths — whether Gen Alphas, Gen Zers or millennials — are resilient and can take advantage of opportunities.

“Many of the things that older generations used to do in the past, we’d say ‘it’s always been like that’ in a way that we tie ourselves down, because we cannot imagine a world that doesn't have all these solid walls,” she said.

“But the pandemic has broken down many of these walls, so there is a potential for younger people to take advantage of these new blank slates. It’s a chance for them to build a better world.”