From studying potential biological weapons to teaching pre-schoolers: A scientist’s unusual career switch

After training for 10 years to be a scientist and building a career in bio-defence, Catherine Ong gave it all up to work with pre-schoolers as a childcare centre operator. CNA Women speaks to the director of Kids and Kins Child Care Centre in this instalment of our series on women who made extreme job switches.

Former senior scientist Catherine Ong gave up a high-flying career to run a pre-school offering children simple kampung-inspired experiences. (Photo: CNA/Alvin Teo)

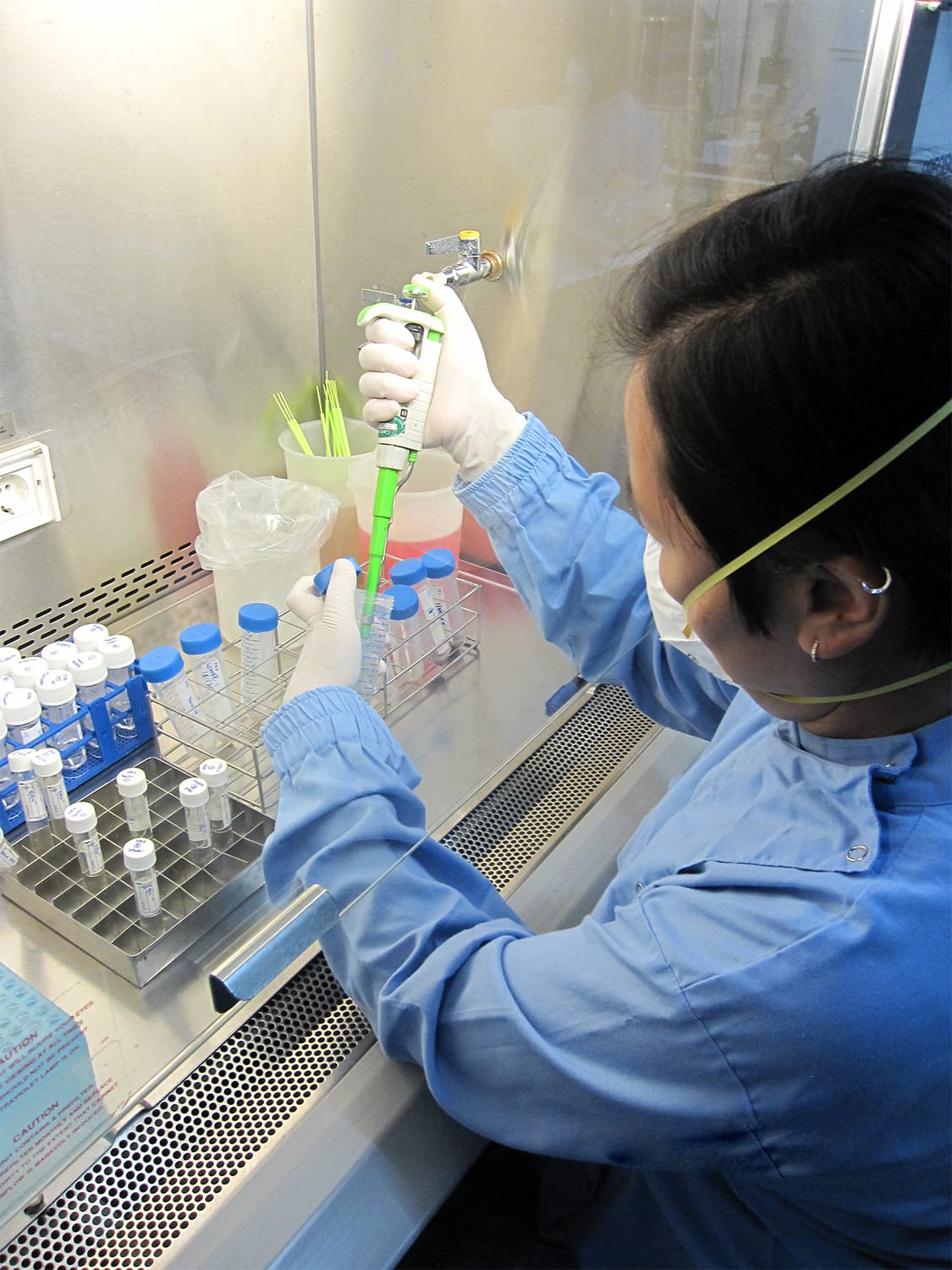

Suited up in protective equipment, Catherine Ong used to spend mornings working with live bacteria in a biosafety laboratory. She was part of the elite team at the Defence Medical and Environmental Research Institute (DMERI) studying potential biological weapons as part of Singapore’s national defence.

Her specialty: The bacteria Burkholderia pseudomallei, known to cause melioidosis, an infectious disease with symptoms such as fever, abscesses, lung infection, bloodstream infection and seizures.

This was highly specialised work. Ong spent more than 10 years getting her honours degree and PhD to qualify for the role. However, after contributing to research for 18 years, she abruptly resigned from her role as senior scientist to run Kids and Kins Child Care Centre in Ang Mo Kio.

Today, the PhD holder spends her days nurturing young children instead.

From scientist to pre-school director, what prompted Ong to make such a sharp career switch? The 45-year-old mother-of-three told CNA Women how her childhood and motherhood experiences shaped two very diverse and dynamic careers.

A KAMPUNG DREAM

In secondary school, where most of her classmates aspired to be doctors and lawyers, Ong dreamt of becoming a botanist.

“I had a very happy childhood spent mostly in my grandparents’ kampungs. There were lots of animals to play with, blooming flowers, as well as durians, rambutans, custard apple and guava fruit trees. I grew up loving plants,” she said.

After her A-Levels, Ong naturally leaned towards studying botany, and cell and molecular biology at the National University of Singapore.

This baffled many of her junior college classmates. “One even asked out of concern if I was going to become a gardener at the Botanic Gardens after graduating,” she recalled.

Ong pushed forward with her dream and spent her undergraduate years memorising the Latin names of hundreds of plants, such as dendrobium crumenatum and melastoma malabathricum. Term breaks were spent in laboratories learning how orchid cells reproduce, and cloning orchid genes.

When she could not find any botany-related jobs after graduation, she joined the DMERI to study melioidosis, working on genomic sequencing, animal infection and environmental surveillance. This cutting-edge scientific work inspired Ong to study for her PhD under a company scholarship.

FROM SCIENTIST TO SCHOOLMASTER

For 18 years, Ong found herself challenged and fulfilled working as a scientist. Then, after having her third child at the age of 38, that abruptly changed.

“I had my daughter after a nine-year gap from my two older sons. Though I took a one-year no-pay leave to take care of my baby, I felt very burnt out when I returned to work,” Ong said, adding that she had to juggle work, care for her infant and two older children, and do household chores.

It didn’t help that her then 10-month-old daughter had severe separation anxiety. “When I sent her to infant care near my workplace, she cried so badly every day that she lost her voice. One day, the supervisor of the infant care gave me this look of disdain and told me sarcastically that my child was so sticky that her teacher couldn’t even leave her to go to the toilet,” Ong recalled.

“I cried on the entire 20-minute journey home that day. I felt guilty for sending her to school at such a young age and not being able to be there for her,” she said. Ong subsequently transferred her daughter to Kids and Kins Child Care Centre, where both her sons previously attended.

Nonetheless, for the next couple of years, Ong remained in a state of burnout. “At work, I found myself staring at my computer screen, questioning what I was doing. Sometimes, I would feel overwhelmed and cry quietly at my cubicle,” she said.

Ong did not suspect postnatal depression at that point. It was only on hindsight that she recognised many of its symptoms.

Her gut instincts told her that she needed a fresh start doing something different. So when she found out that the owner of her children’s pre-school wanted to retire and was looking for a successor, she jumped at the opportunity.

“I love the family-like ambience at Kids and Kins, and always had an interest in nurturing young children,” she explained. “But when I met the owner of the centre and we started coming down to dollars and cents, I almost backed out because I was worried I might not have the financial means and practical experience to pull it off,” she admitted.

Because of her close relationship with the school as a parent, the owner unexpectedly gave Ong a 50 per cent discount off the original sale price and taught her how to run the business. This emboldened Ong to resign from her job as senior scientist and plunge into early childhood education in 2019.

RECLAIMING A PIECE OF HER CHILDHOOD

Ong and her husband emptied their savings to buy over the business and Ong took a huge pay cut.

When she first took over, enrolment at the centre was at 30 per cent of full capacity, with only 20 to 30 children in total. A year later, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Ong worried the business would fold.

However, Ong kept her focus on overcoming day-to-day operational challenges during the pandemic. “My infectious disease training came in handy. I knew how to analyse the trends of infection and pre-empted teachers and parents if there was going to be a spike.

“I also explained the symptoms of the disease to my staff and trained them in laboratory disinfection standard operating procedures,” she said.

“I knew home-based learning would be challenging so my team prepared worksheets and art and craft materials for our children, and my principal and I personally delivered these packages to each family during the circuit breaker. My team also supported parents throughout the pandemic and advised them on how to cope with home-based learning,” she shared.

Despite the pandemic, enrolment at the centre grew threefold over the next three years. Today, the centre has almost 90 children and is running at close to full capacity.

As director, Ong is extremely hands-on, clocking in seven days a week to take care of operational, administrative and teaching duties. She and her husband even make weekly trips to personally buy fruits and other perishable food items for the school.

“Sometimes, it’s these little joys that make the whole operation fulfilling. You feel like you are running a big family and are picking out the best for your family,” she reasoned.

Inspired by her own kampung childhood, she built a mini farm with 50 different plants within the school compound, including flowers such as orchids and roses; herbs such as mint, basil, pandan leaf and lemongrass; and fruit trees such as papaya, banana and chiku.

She also set up a mini fowl farm with around 10 birds, including jungle fowls, silkies and quails. “My husband’s ex-colleague was breeding quails and gave us some eggs so we incubated them in our centre to let the children observe the process,” she recalled.

Her husband later found abandoned jungle fowl eggs in an exposed spot in a car park in the Sin Ming estate, which the couple incubated as well. Ong also subsequently adopted more quails and silkies.

Today, Ong uses the mini farm as a natural classroom, teaching the children about plants and insects, and collecting leaves, twigs and stones as materials for numeracy and pattern recognition classes. Sometimes, the children help to water the plants, feed the fowls, and even enjoy herbs and quail eggs from the farm as part of their lunch.

“Singapore is getting so urbanised that children nowadays are missing out on the simple joys found in nature,” she said.

“Many children today are highly intelligent but lack basic skill sets such as how to identify simple vegetables or tell if a fruit is ripe. Growing up in a kampung, my parents gave me the freedom to explore on my own, and pluck and smell the vegetables and fruits. I created this mini farm so that the children in my centre may also enjoy a carefree childhood, and pick up basic skills that will carry them through life,” she added.

Ong admitted that she never expected her postnatal depression to lead her down this new fulfilling path and build her a new “extended family” of kids and kin. “Every December, as I watch the K2 graduation concert, I would cry. It is very fulfilling to see these children grow up happily and healthily day after day as though they were my own,” she confessed.

“Watching them move on to the next chapter of their lives and reflecting on how much I will miss their laughter, cries and tantrums makes me very emotional. It makes me feel like I have done something good and made the correct decision to choose this path.”

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg (CNAWomen[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg).