Plum Village: Meet the 78-year-old keeping alive one of Singapore's last Hakka restaurants

CNA Lifestyle speaks to one of Singapore’s last Hakka restaurateurs to find out how he’s been preserving traditions for 41 years and counting.

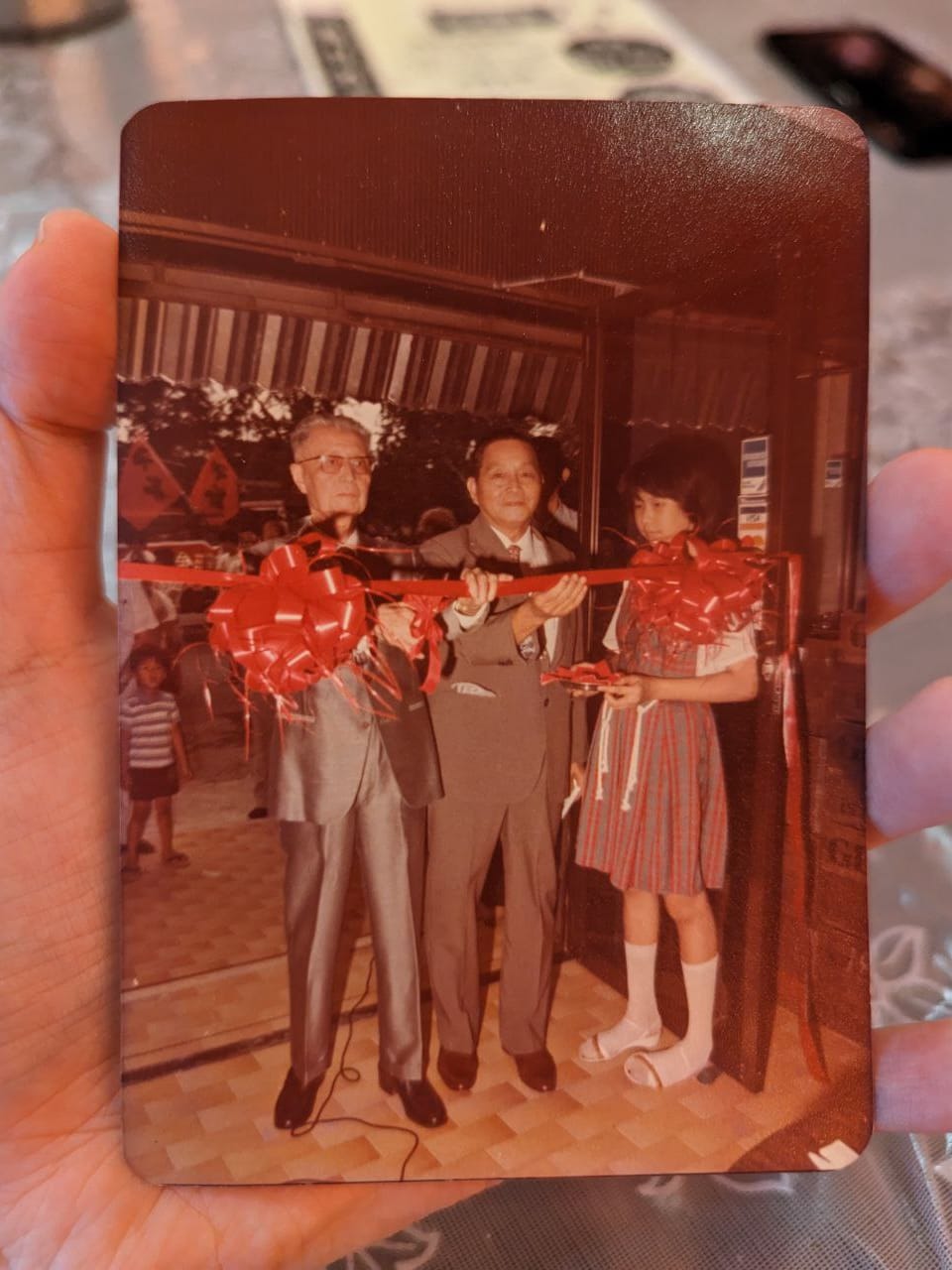

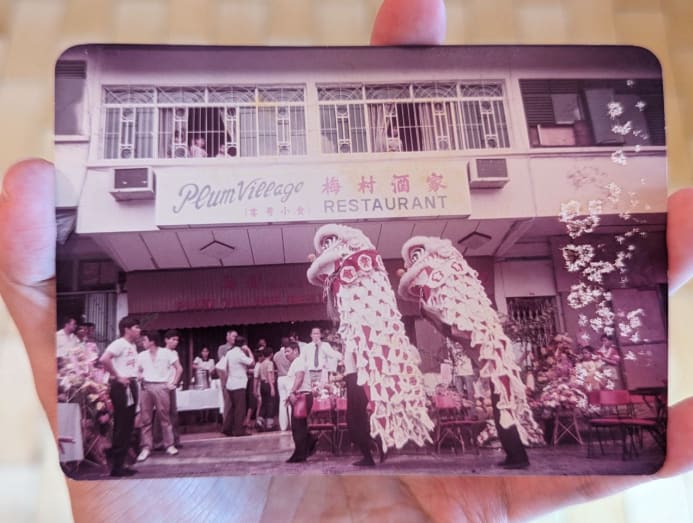

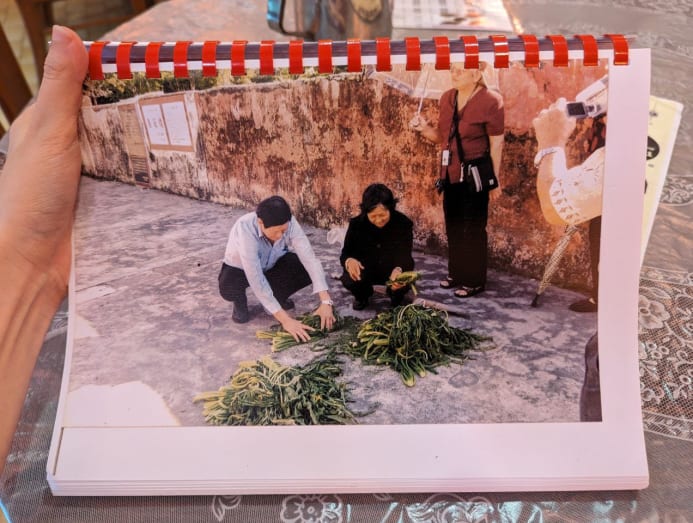

Plum Village restaurant then (left) and now, with owner Lai Fak Nian. (Photos: Joyce Yang)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Yong tau foo is so ubiquitous, it has a place next to the sushi and delicatessen counters in the supermarket. But if the name calls to mind a medley of vegetables, mushrooms, and soy products stuffed with ground fish paste, you could be missing out on the traditional yong tau foo experience.

But Hakka yong tau foo, distinguished by its use of minced meat instead of ground fish paste, is rare. It’s right up there with abacus seeds and thunder tea rice, among the legion of Hakka dishes bordering extinction. In fact, as of January 2024, possibly only one Hakka eatery remains in Singapore. Its name is Plum Village Hakka Restaurant, owned by 78-year-old Lai Fak Nian.

FROM TOA PAYOH TO JALAN LEBAN

“Back in the day, we ran a general store here, catering to British servicemen towards the end of their time in Singapore,” Lai said of his shophouse at 16 Jalan Leban.

It’s not the only relic here; there’s also a taxi stand labelled "Sembawang Hill Taxi Services" and a 5-digit telephone number.

“A Hakka chef from Hong Kong noticed that we didn’t have an authentic Hakka restaurant here, so he suggested starting one with my father. We thought it would be a great way to keep Hakka culture alive in Singapore.”

It would seem that Lai’s father stumbled into the trade by virtue of being Hakka, as he had no culinary background to his name. But he was a businessman and, according to Lai, the 1970s were the cuisine’s heyday (a good 70 per cent of F&B establishments in Hong Kong were Hakka restaurants).

In 1969, Lai’s father started the business with five other stakeholders in Toa Payoh Lorong 4. For Lai, who was in his early twenties then, time in Toa Payoh is synonymous with one of the most memorable banquets they’ve ever thrown.

"Back in the day, there were few restaurants and there was no such thing as a hotel wedding. We must have set up around 80 tables outside the restaurant for close to a thousand guests and a convoy of bridal cars,” Lai described.

Alas, it wasn’t the windfall they’d expected. At 8pm, the guests were a couple of courses in when a storm struck and wrecked the setup. All at once, nearly a thousand guests upped and left without paying. Lai was crushed, and there was only one thing they could bank on the following morning: Their goodwill.

“Nobody dared to knock on doors and ask for money this way because we’re talking about the sixties and seventies when gangsterism was rife in Toa Payoh,” he explained.

“I steeled myself and went to all corners of Toa Payoh personally, explaining our situation and trying to get as much money back as possible. Thankfully, we managed to recoup half the amount and cover our costs.”

This hardly deterred Lai from staying the course even after the restaurant in Toa Payoh wound up (the owners parted ways after five years). He spent the following years perfecting his craft in various kitchens and asked for his father’s blessing and backing to revive the business in 1983.

“My dad replied, yes, you can start a Hakka restaurant. But what is your vision? I figured that we Hakka people come from seven different areas, and not every area has many specialties to show for. So, I wanted to bring them together in one place so no one is left out when they come to Plum Village in search of Hakka cuisine,” he explained.

But as the economy looked up and people grew wealthier in the eighties, seafood restaurants sprouted everywhere and Hakka cuisine began to lose its shine. It didn’t help that, by Lai’s estimate, the Hakka community made up less than 10 per cent of the local population.

“I figured I couldn’t just cater to the Hakka community; I would have to showcase our cuisine to the wider Singaporean population,” he said.

With that, Plum Village Hakka Restaurant was given a second lease of life in 1983.

“I JUST NEEDED TO KEEP ONE SHOP ALIVE”

“When we first opened, we were a sorry sight,” Lai recalled.

No more than five tables were occupied on the first day and the rest of the week was quiet. It wasn’t until they were featured in the papers that people started streaming in.

Said newspaper clippings are plastered throughout the restaurant, along with a poster-sized photo of 37-year-old Lai, apparently taken on one of his field trips to China. He remembers 1983 as his busiest year of work yet. He’d had to fly back and forth, keeping his fingers crossed for more hits than misses with the recipes he procured straight from the source.

“When customers keep coming back for more after the first six months and place their orders without needing a recommendation, that’s a telltale sign that your restaurant has taken off,” Lai shared.

“Nine out of ten of our customers aren’t Hakka, but they got used to our cuisine in no time. They polished everything off, which really gave me the confidence to bring in more Hakka dishes.”

At the peak of its prosperity, people would line up as early as 5pm for dinner service. Lai admitted that he had let his initial success get to his head, unveiling four additional branches in the next three years and biting off more than he could chew.

“In 1997, my children graduated from university and expressed no desire to take over. That same year, my uncle and right-hand man also got into an accident. I had to wind up the four branches or the flagship would be neglected,” he shared.

“My friends encouraged me to do so, saying that the business would take a physical toll on me. They told me I just needed to keep one shop alive.”

The flagship is as much Lai’s as his customers’, and many of his regulars are grandparents with their children and grandchildren in tow.

“Many of them tell me, ‘We don’t just come here for the dishes. We come here out of nostalgia for the good old days. If you were to close the restaurant, we would feel quite lost,’” Lai said.

Plum Village started out as a repository of Hakka culture but ended up safeguarding much more than that, including family traditions. Lai shared a bittersweet memory about a father and son who made a ritual out of ordering two large portions of pork belly and preserved vegetables (a portion serves five).

“One day, he told me that his days of enjoying the dish are numbered because he had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. After he passed on, we never saw his son anymore. Perhaps being reminded of their fond memories here is too painful.

“It saddens me to this day. After all, I had been cooking for them for years. Running a restaurant has its happy moments, but there are difficult moments too.”

THE POON CHOI INCIDENT

Hakka Poon Choi is a simpler affair compared to its Cantonese counterpart, but preparing hundreds of orders, as Lai did three years ago on Chinese New Year’s Eve, was far from simple.

“Maybe we were too ambitious,” he said as he reflected on the restaurant’s misstep in 2021 – the year Singapore started recovering from the pandemic and Chinese New Year gatherings shrunk. Considering the restaurant received 232 orders for the festivities, they should have started the year off right. Instead, a series of unfortunate events unfolded.

“The delivery men swarmed into the restaurant once the orders were ready, and all our safe distancing measures flew out of the window. I left my post in the kitchen to do crowd control, which turned out to be the biggest mistake.”

Long story short, chaos ensued and about a third of the orders went unfulfilled. That evening, seventy odd families stared at the empty spot on the table where their Poon Choi should have been.

“I thought: Oh no! People weren’t getting their reunion dinners – that wouldn’t do. Our phone rang furiously and none of my female employees dared to answer.”

The restaurant made the headlines on the second day of Chinese New Year, which Lai spent calling every customer personally to apologise. Additionally, he offered to refund their deposits and deliver their rightful orders anytime during the festive season at no charge.

“My losses and stress levels were through the roof that year, but there was no other way out. We had to make it up to our customers,” he recounted.

THE ROAD AHEAD

Since Hakka food is in demand, why aren’t there more like Plum Village Hakka Restaurant? Lai alludes to the fact that Hakka cuisine, which features simple ingredients his ancestors could source on the hilltops, is not a lucrative business.

“Frankly speaking, you can’t make much selling Hakka food. When you serve a table of ten, the bill may not even come to S$200,” he said.

If he didn’t own the shophouse, he conceded, the restaurant wouldn’t have survived the pandemic, and he wouldn’t have stayed in this trade for 41 years and counting, even as his contemporaries pivoted to businesses with higher margins.

“It all boils down to what interests you. I do feel a sense of mission in running this restaurant, and so long as I can cover costs and keep Hakka culture alive, I’m okay with it.

"I thought I would retire at 60, but after thinking about it, I realised that I wasn’t ready to let go. Talking to our regulars made me think, okay lah. Just keep it going lor.”

This may explain why the restaurant was rumoured to close for good in 2017, a piece of news that garnered interest from buyers, investors, and the Hakka clan in Singapore. From these talks, working as a consultant emerged as an option for Lai to continue fulfilling his life’s purpose while enjoying his golden years.

Then there were rumours that his son would leave his job as an accountant to take over, which were also untrue. In fact, we were told this Chinese New Year would be one of their last.

“There’s no need to drag it out, so I’m thinking about another two or three years. My mom is 98 years old, and she probably has another three to five years to live. What would be the point when she’s no longer around?”