Meet the fourth generation heir of Tong Heng, the egg tart empire founded in the 1920s in Singapore

Spotted Tong Heng’s modernised new look and feel? CNA Lifestyle interviews the creative force who revitalised her family's business, which is almost a century old.

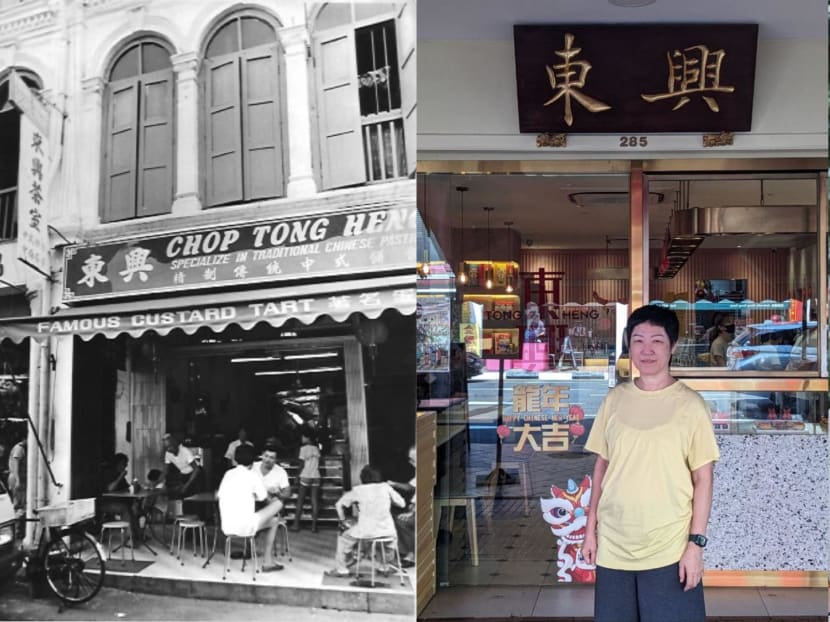

Ana Fong (right), the fourth generation showrunner of Tong Heng, which has been around since the 1920s in Singapore. (Photos: Joyce Yang, Tong Heng)

There’s a Chinese saying that goes: “Wealth does not last beyond three generations.” But whoever said that simply hasn’t met Ana Fong, the chief operations officer and fourth generation showrunner of Tong Heng.

For Singaporeans, Tong Heng is synonymous with their diamond-shaped egg tarts, among other traditional Cantonese pastries. According to Fong, Tong Heng sells around 1,000 egg tarts a day and up to 3,000 on good days. As of 2024, they’ve got two stores in Jurong and Chinatown, where the bakery stands as a rare centenarian-to-be.

How have they kept the family business alive for nearly a hundred years? Why stop at two outlets? And have their egg tarts always been diamond-shaped? CNA Lifestyle finds out from the 59-year-old heiress of Singapore’s egg tart empire.

BEARING WITNESS TO SINGAPORE’S HISTORY

It may surprise you that the late Mr Fong Chee Heng, Ana’s paternal great-great-grandfather, never intended Tong Heng to be a pastry shop. Instead, it was started in the 1920s as a streetside drinks stall in Pasir Panjang.

“I used to think that Tong Heng was a kopitiam until I looked at some of the old things we have. They said Tong Heng cha sat, which means tea house. That means the first and second generations saw it as a level higher than kopitiam,” said Fong.

Tong Heng didn’t start selling Cantonese pastries until they moved to 33 Smith Street in 1935, across from the former Lai Chun Yuen Opera House, and introduced their signature egg tart and traditional omelette toast (similar to French toast, but made with lard).

In fact, the public can learn how to make these at the Five Footway Festival 2024, a homage to Chinatown’s history happening from Mar 9 to 17.

“During those days, whenever there’s a performance, Tong Heng can operate till 3am. It’s not unusual for fans to order our omelette toast for the artistes.”

In the 1940s, the Japanese occupation brought the festivities at Lai Chun Yuen to a screeching halt. When a bomb landed on the opera house, Fong said, its impact fell Tong Heng’s wooden entrance to the ground. In spite of that, Tong Heng stood its ground throughout the war. In fact, the first and second generations recalled business to be particularly brisk.

“People understood that for all they knew, it may be the last day of their lives. Even if it were their last S$10, they would want to enjoy a bit of it. So they were more willing to buy food to treat themselves,” Fong explained.

The picture she has of pre-war and wartime Tong Heng may be a product of stories from the first and second generations, but this changed by the time her grandfather took over. The latter wasn’t much of a family man, according to Fong, and channelled all his energies into putting bread on the table and building the community in Chinatown.

“His passion, his spirit, and his heart were for the community. Every night, he’ll make a trip to the community club to make sure that everything is well,” she recounted.

As the community club sat on a hill, her grandfather would bring the opera tickets to Tong Heng so elderly showgoers could purchase them more conveniently. And when the 1970s ushered vendors into hawker centres, to the displeasure of many, he took it upon himself to make the transition easier for everyone.

“He went to the bank, changed a van full of coins, and placed them in a store so the hawkers didn’t have to queue at the bank. They could just go to the store and change money.”

Tong Heng moved to its current location along South Bridge Road in the 1980s, when its egg tarts settled on the diamond shape. Up to this point, they had been circular, oval, triangular, and even leaf-shaped, until Fong’s two aunts – whom she calls “the brain and the brawn” – came onboard as the third generation.

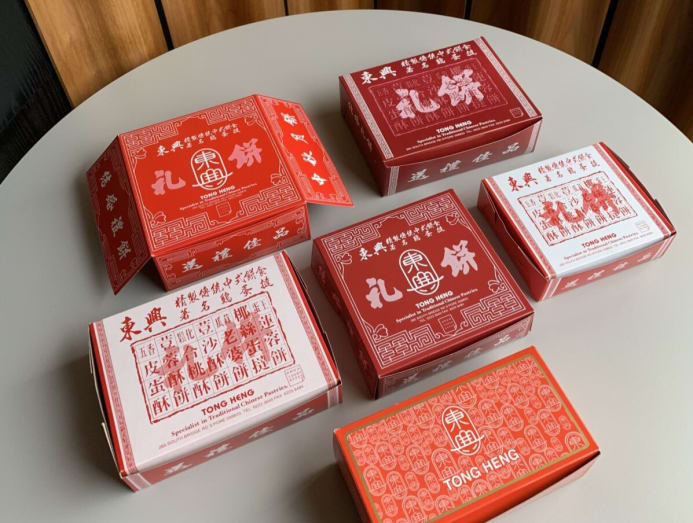

“It was around that time when the Chinese started moving away from dowry cakes and towards wedding cakes. My aunt – the ‘brain’ – said if that continued, no one would know that we Chinese have our own dowry cakes.”

A facelift for Tong Heng’s dowry cakes ensued, culminating in a custom-sized box that fit the wedding pastries and, as a cherry on top, their signature egg tarts. And how did they make the most of the space within? With diamond-shaped egg tarts, of course.

“WORKING AT TONG HENG WOULD FEEL LIKE SELLING MY SOUL”

This marks Fong’s 12th year in the family business, a venture she only embraced after several detours in her working life. Sure, she had helped out every now and then, but the idea of carrying forward her family’s legacy seemed too suffocating for her younger self.

“Knowing my character, I knew that working at Tong Heng would feel like selling my soul. I had a very long conversation with my aunt and politely explained to her that I am not interested in taking over the family business,” she recounted.

“The beauty about being in this family is that they’re not the type to (force). They will respect your decision.”

Fong’s approach to her career can be aptly described as laissez-faire. She transitioned from a fragrance salesperson to a jewellery design student at LASALLE College of the Arts and a Chinese tutor, attributing her pattern of job-hopping to her privilege.

“I’m very blessed with the fact that coming from this family, I don’t have to feed anyone. I lived my life like a no-brainer. Work ah? Work lor. There’s no pressure to do anything properly, so the first couple of decades were ‘wasted’ in a way.”

When Fong wasn't working, she was often found travelling and volunteering. However, over time, her introspective journeys brought about a realisation: If she had the capacity to help strangers in distant lands, what about her loved ones back home?

“That’s when it hit me, that it’s a bit hypocritical if I didn’t look near me. My aunts were ageing, and they had unfulfilled wishes,” she shared, adding that one aunt – the “brain” – was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease some 20 years ago.

Fong found herself torn between honouring her sense of filial piety and pursuing her individualistic ideals. While she felt a sense of responsibility to her elders, she also found herself looking for an escape hatch.

“When I went back, I didn’t want anyone to have the expectation that I’d be here forever, just in case I realise I don’t like it after all. I just said, can I come back to work? You seem quite shorthanded. Let me help.”

In the beginning, Fong dedicated at least 10 hours every day, seven days a week, to her work. She viewed her role as merely a checkbox item, determined to "learn fast and get out fast." However, by her third year, she had mastered the craft, and it started to resonate with her. It was also at this point a eureka moment struck.

TONG HENG’S TRANSFORMATION

Before, most customers of Tong Heng were females in their forties and young patrons were few and far between. Recognising that the brand's appearance might be the issue, Fong bravely broached the topic with her aunt, suggesting a change.

“That was not a nice remark to her, because the store layout and packaging were done by her. Even some of the calligraphy was handwritten by her,” Fong said.

“To her, it was like, ‘who’re you to tell me we should change the packaging?’ Obviously, she did not say this to my face, but I imagine this went through her head.”

Surprisingly, Fong’s aunt showed no overt objection. Perhaps she saw it coming, considering Tong Heng’s adherence to tradition over four generations. Sensing the latter’s ambivalence, Fong approached the rebranding exercise with caution and imposed three conditions on the creative agency.

Firstly, the new look and feel should attract younger customers without alienating their loyal regulars. Secondly, Singaporeans who had been referring to Tong Heng as “that egg tart store in Chinatown” should know them by name. Lastly, any alterations to the logo, a product of her aunt's creativity, should be minimal. Unfortunately, the last aspect went unchecked.

“(My aunt) almost broke down in tears. Why? Because they changed the logo. When I saw the new logo in the first minute of their presentation, I thought: Oh no. Why’d they change it?

Apparently, the team deemed the original logo too subtle to make a statement. The new design was more assertive, boldly proclaiming Tong Heng's name and delivering the impact Fong desired. Despite her initial reservations, she couldn't argue with its effectiveness.

“My aunt was angry with me, and I was not forgiven for almost two years when the new look was rolled out.”

Although her aunt eventually embraced the rebranding, she made it clear to Fong that Tong Heng's identity as a Chinese brand must be respected. When it came to creating new products, for instance, fusion with Western ingredients was out of the question. Instead, Fong explores ingredients a Singaporean might find in their grandmother’s kitchen or the traditional Chinese medicine store.

“COME BACK WHEN YOU THINK YOU’RE READY”

Tong Heng’s regulars may remember their foray into franchising, with stores sprouting in Takashimaya and Changi Airport for a brief moment in time. However, they discontinued these ventures when they noticed a decline in product quality.

Whether there will be a third outlet isn’t the only question on people’s minds; many are also curious about the potential fifth-generation owner. Even though the future remains uncertain, Fong’s niece – a recent graduate working in consulting – has been helping out every now and then.

“It happens that the project she holds is quite slave-driving, but I appreciate whatever she’s doing. Regardless of how busy and tired she is, she will come down every weekend to help me out.”

While Fong values her niece's involvement, she manages her expectations, much like her aunts did years ago when Fong dreamt of exploring the world beyond their small shop along the five-foot way.

“I said, I want you to soak up all the experience outside because I have been through it myself. I want you to learn everything and come back when you think you’re ready. She never said no, but she never said yes.”

So, how did Tong Heng break the third-generation curse? Perhaps it was the freedom each generation offered the next to carve their own paths before returning to Tong Heng. And when the younger members did come back, they were given autonomy to shape their family business.

A decade ago, when Fong joined Tong Heng, she was driven by a sense of duty. Today, she finds fulfilment in pursuing her personal aspirations through Tong Heng, donating a portion of the store's proceeds to charity and engaging with the Chinatown community, following in her great-great-grandfather's footsteps.

“In Chinatown, I’m able to mingle with stakeholders who are keen to promote our Chinese culture. Through food, we can let the younger ones know some of the practices that are very much diluted or even gone. Maybe this is another meaningful thing I can put more effort into.”

Visit the Five Footway Festival website for more details. The event runs from Mar 9 to 17 in Chinatown.