She struggled to see, walk and breathe since birth but never stopped dreaming: ‘I learned to become my own cheerleader’

Syarnissa Dahuri, 34, was born with medical conditions that left her visually impaired, with breathing difficulties and mobility problems. Even so, the Malaysian proudly calls these her “superpowers” and lives life as independently as she can, helping to create opportunities for people with disabilities in the corporate world. As told to CNA Women's Izza Haziqah.

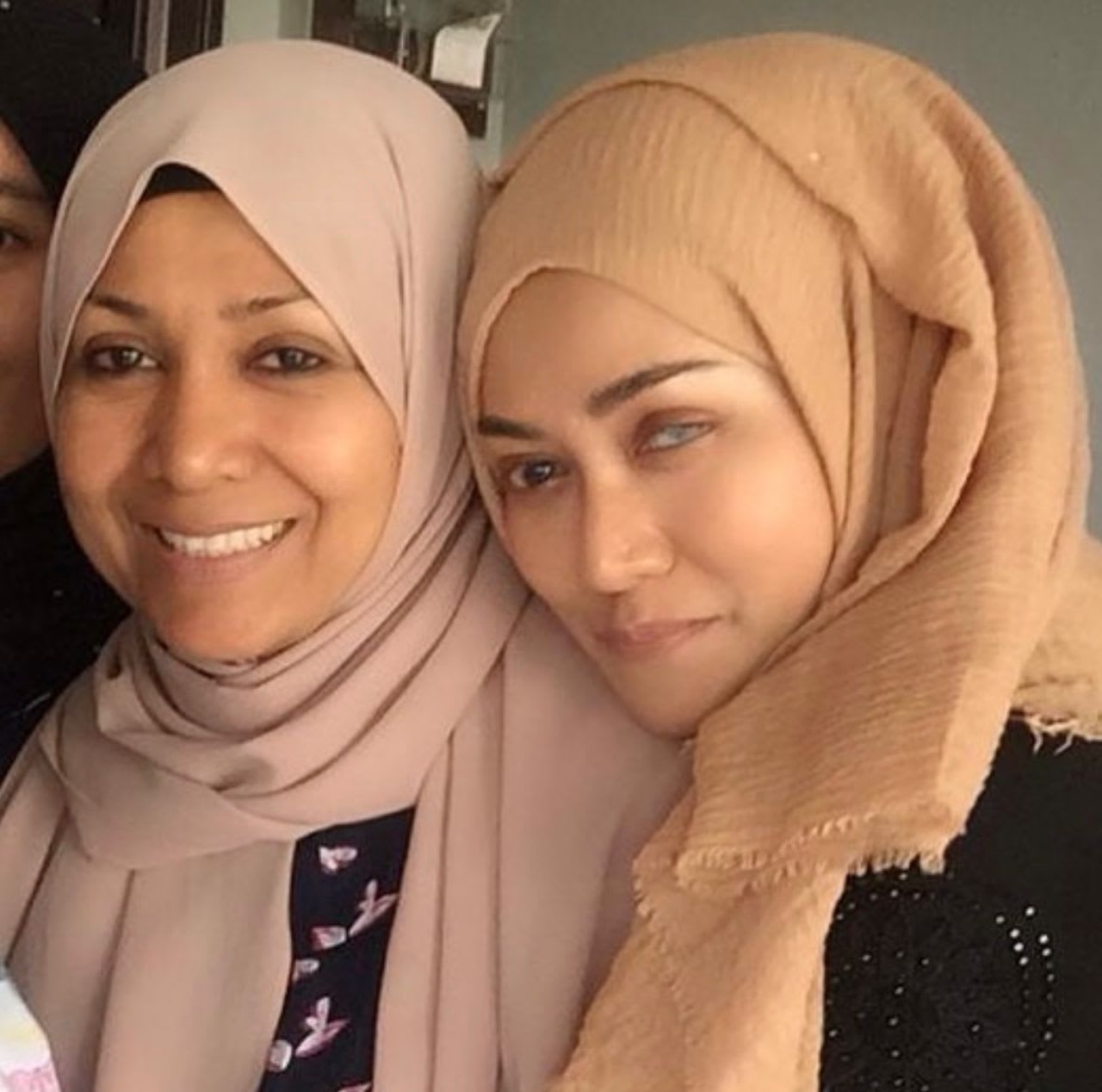

Syarnissa Dahuri, 34, was born with bilateral congenital glaucoma, spina bifida and chronic lung disease, which left her visually impaired with mobility issues, respiratory difficulties and other health problems. (Photo: Syarnissa Dahuri)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Whenever I sit for a job interview, I worry about three things. First, whether I’ll impress the interviewer with my credentials. Second, whether the interviewer will find me a good fit for the company. And third, whether the interviewer will be so distracted by how blue my completely blind left eye is that they can’t focus on what I’m saying.

I was born with bilateral congenital glaucoma, a medical condition where both my eyes were affected by increased pressure that damaged the optic nerve. My left eye is completely blind and my right eye has only 2 per cent vision, down from 15 per cent when I was born.

I also have spina bifida, a birth defect where the spine and spinal cord don’t develop properly. As a result, I have problems with movement and sensation, especially in my lower body.

Lastly, I was born with a type of chronic lung disease which caused me to have respiratory issues, making it difficult for me to breathe.

To get by, I rely on many tools. I use a digital screen reader to read and write, a cane to move around with and support my back, and lots of different medications and colourful pills to control and regulate my pain and breathing.

People call them disabilities, and while I don’t disagree or have any problem with the word ‘disability’, I don’t fully resonate with that. I call them my superpowers because they are what make me special.

GROWING UP WITH THREE ‘SUPERPOWERS’

With three ‘superpowers’, my childhood in Kelantan, Malaysia, where I was born, was filled with many medical appointments.

As a toddler, instead of playgrounds, I grew up in hospitals, clinics and operating theatres. My time was divided among the departments of ophthalmology for my eyes, neurology for my brain and spinal cord, and respiratory for my lungs and breathing. To date, I’ve had dozens of surgeries, mostly for my eyes and back.

Despite all that, and because of my family, I have many fond childhood memories.

My parents ferried me to my medical appointments, made our house easier for me to move around in, and even though they worried about me, didn’t keep me in the house. They would take my siblings and me out so we could enjoy ourselves.

I could have felt like a burden in many ways but my family never treated me that way.

I am the middle child, and my older sister and younger brother had my back – literally and figuratively. My sister, especially, would help me move around the house and when we were outside until I didn’t need her help anymore. She would dress me up in nice clothes, apply makeup on me, and help me with my schoolwork.

I could have felt like a burden but my family never treated me that way. They’re a precious support system and without them, I would never possess the confidence I have today.

AN EDUCATION SYSTEM NOT DESIGNED FOR ME

As I grew older, I came to realise that a lot of places weren’t as disabled-friendly.

At seven, when I was ready for school, I insisted on attending a public school instead of one for the blind. At first, it was to show I could thrive in mainstream education. Later, it became my goal to get a full education so I could help others like me in the future.

My parents took a leap of faith and agreed, and I went to a government school in Kelantan.

Back in the 1990s, learning was largely pen- and paper-based, making it challenging for me as I couldn’t see. I relied on my teachers to read aloud, and generous classmates to help me move from one classroom to another.

While my family provided a comfortable and empowering haven for me, the rest of the world was harsh and was not as open to my conditions.

Due to my conditions, and especially my blue eye, I was not spared from teasing – other kids called me names like "zombie" or "alien". It was also hard to make friends. While some were nice to me, it just wasn’t easy to accommodate someone who couldn’t see and had trouble walking and breathing.

When I was 10, I was asked to leave my school because it lacked the resources to support my needs.

At that point, I felt dejected. While my family provided a comfortable and empowering haven for me, the rest of the world was harsh and was not as open to my conditions.

It was as if the world was telling me that despite my confidence, I was still different from everyone else. There was even a time when I felt it was better to not have been born.

But I had a goal. I didn’t want to give up even though it was tough.

I learned to become my own cheerleader. I reassured myself that it was fine to seek help and not feel like a burden and that it was okay to slightly inconvenience others to get what I needed.

I call them my superpowers because they are what make me special.

Thanks to my parents’ determination to look for a more accommodating and disabled-friendly school, I enrolled in another government school.

With my family’s support, I learned to read and speak in Malay and English, and memorise the letters on a standard keyboard. I did well in school and even had a part-time job tutoring younger students in English.

I juggled my time between medical appointments in Kelantan and Kuala Lumpur, studying hard for my examinations, and my job as a tutor.

My achievements kept me going – sometimes, I was even surprised by how well I did academically, despite all the negative things I was told about my disabilities.

I started believing in myself more, and I no longer felt bad about myself or the way I was born.

In about 10 years after being asked to leave my first school, I completed my primary, secondary and pre-university education.

DISCOVERING AND BUILDING OPEN-MINDED COMMUNITIES

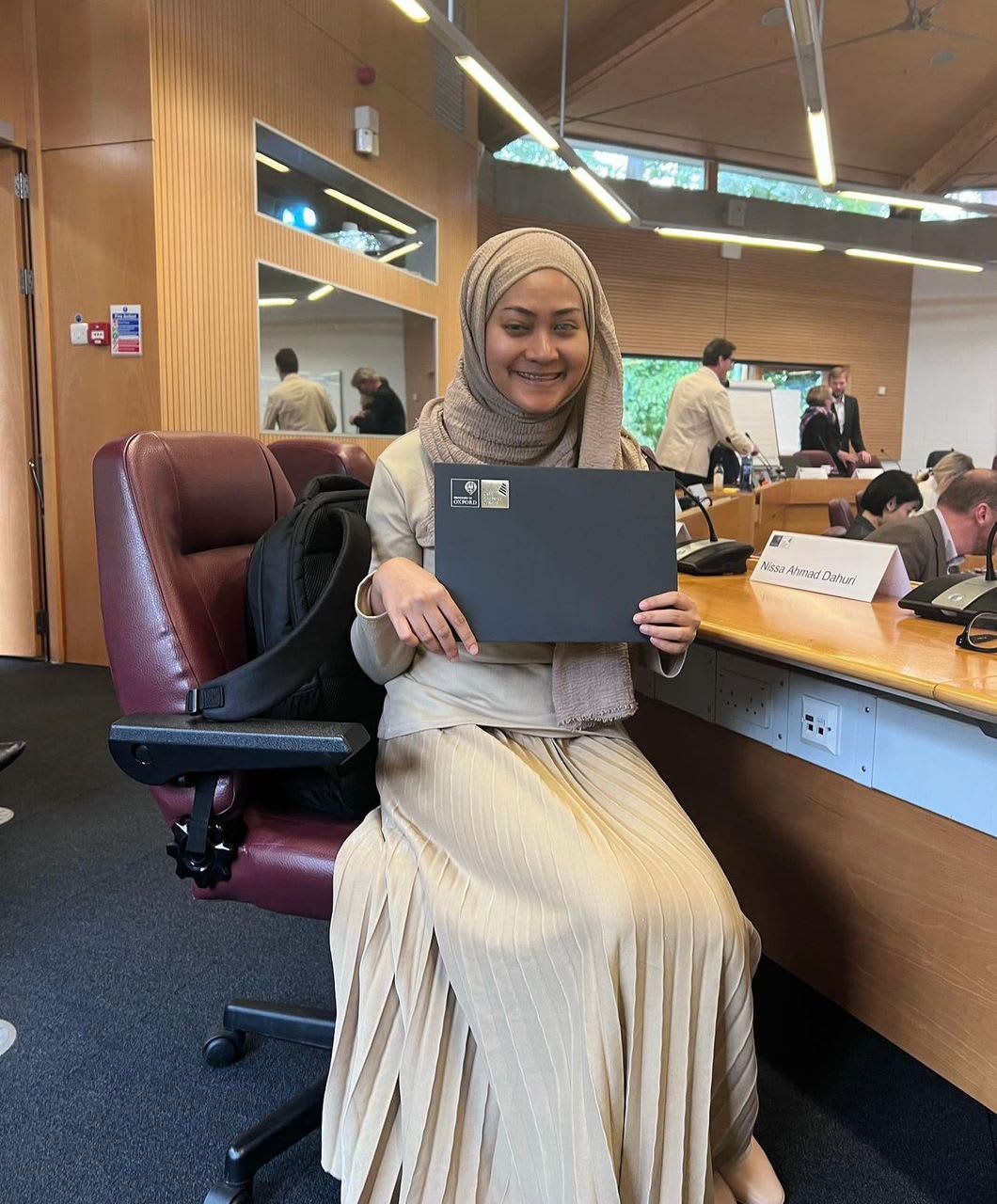

After completing my pre-university education at 21, in 2010, I was offered two university scholarships. I could have chosen to study in Malaysia where I was comfortable, but I decided to pursue accountancy at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

My decision to study overseas made my parents very worried and anxious for my well-being, but I will always be grateful that they trusted me enough to let me go.

I had the best time of my life studying in Australia. I found open-minded friends, connected with disabled-friendly communities, and grew significantly in confidence as I learned to live overseas on my own.

It was an empowering period and I felt like a bird – I could spread my wings and fly freely.

I lived on campus with four housemates who included me in all their activities and never made me feel odd about my disabilities. I even befriended a lovely local family who welcomed me into their home and frequently took me out on weekend outings or short trips around the city.

Even today, I occasionally keep in touch with some of my former housemates and the family.

It was also during my undergraduate years that I started to travel solo. At first, it was terrifying but I realised that most people, no matter their capabilities, are also scared when they travel alone for the first time.

Like them, I too found my way around places by reading on the internet how local systems work, and I would reach out to strangers if I needed help.

Some countries, like the United Kingdom and New Zealand, are also more disabled-friendly and it was easier for me to explore them on my own.

To date, I’ve visited over 20 countries, the majority of which are solo adventures, such as Bosnia, Japan, Turkey, Croatia, and Hong Kong, and I've even performed my religious pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia.

I’m excited about going on future travels, whether solo, with my family, or with a future husband who shares my values, as we build our own family together.

However, after I graduated in 2012 after two years of studying in Australia, the experience of searching for a job in Malaysia brought back memories of when I was 10.

I met so many rejections – literally, in the hundreds – and some employers would blatantly tell me that someone with my conditions could never do the jobs I aimed to do, which included roles in strategy, communications and project management.

But after 23 years of constant struggle to make space for myself and my parents’ endless sacrifices, how could I give up?

I took things one day at a time and looked for more disabled-friendly roles. Within a few months, I secured a position in community projects at a multinational company.

It has been more than 10 years since then. I’ve worked in four different companies, in roles that helped to make corporate opportunities accessible to others with disabilities, such as those with visual impairment, hearing challenges and mobility issues.

After 23 years of constant struggle to make space for myself and my parents’ endless sacrifices, how could I give up?

The world may be harsh and designed by default for people without disabilities, but that doesn’t mean we can’t raise more awareness for a more inclusive community.

It goes beyond simply hiring individuals with disabilities; it involves breaking mental barriers and moving past the limited belief that those who are blind or have disabilities are confined to only so few capabilities.

I used to feel bad about being born, but now, I’m grateful to forge all kinds of paths for others like me.