‘It really humbles me’: Prison teacher on what it’s like to help inmates with their N-, O- and A-Level exams

Emelda Jumari has been teaching at Prison School for six years and she talks to CNA Women about the unique challenges of her job, including earning the trust of the inmates and adjusting her teaching methods to suit their different needs.

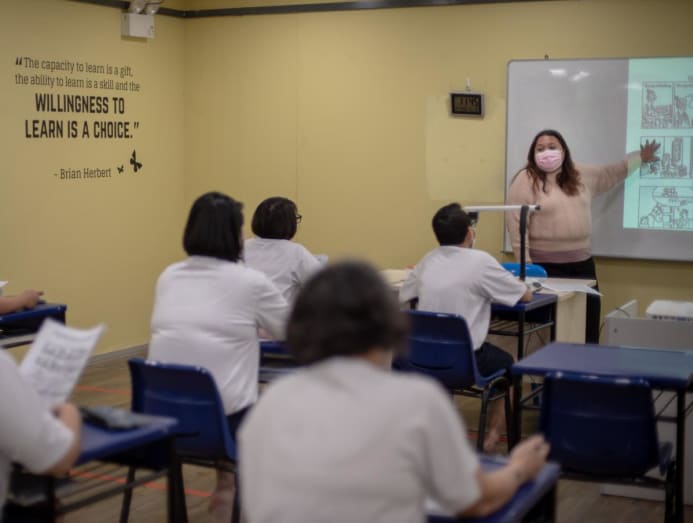

Prison School teacher Emelda Jumari reflects on what it’s like to wear multiple hats at once – as an authoritative figure, a role model, a “big sister figure” and more – in the classroom. (Photo: Singapore Prison Service)

It was early 2017 and Emelda Jumari had just received a call from a good friend, telling her of a job vacancy at the Prison School. She was on a break from work then, having previously been a secondary school teacher for five years, and recently completing a short stint at School of the Arts Singapore.

Prison School is part of Singapore Prison Service’s education programme to provide learning opportunities for inmates, reducing the risk of re-offending and increasing their employability upon their release.

The school needed a teacher and Emelda decided to give it a try: “That (call) was a game-changer. I’ve heard about Prison School, but I never thought that I’d be a part of it.”

Emelda joined Prison School as a teacher in April 2017. She teaches English and Malay across different levels, including General Level (which is equivalent to Secondary Two), N-, O- and A-Levels.

CHALLENGES OF TEACHING IN A PRISON SETTING

But getting the job was just the start. “I came in with zero knowledge about what it’s going to be like,” the 38-year-old recounted to CNA Women.

I’ve heard about Prison School, but I never thought that I’d be a part of it.

Inmates have to go through a placement test prior to enrolling in Prison School. Their most recent educational qualifications, and their conduct and duration of incarceration are also considered.

Emelda found she had to adapt to the differences in student profiles – inmates in the same class could range from as young as 18 years old to those in their 60s. “That was definitely a challenge to any teacher, in terms of the pedagogy that you use, your approach, and the kind of support the inmates need.”

In her first year on the job, she recalled teaching a group of male inmates who had a nose for trouble. When they were together, she recounted, there would be one or two more “rebellious” or “outspoken” ones who would attempt to challenge her authority.

“This is normal because they’re testing (me) to find out what type of teacher (I am),” said Emelda.

She managed to gain her students’ trust by talking to them one-on-one, and asking them what they were frustrated with. They quickly realised that she genuinely cared for them. “It’s my personality, I’m quite bubbly by nature.”

FINE-TUNING HER TEACHING METHODS

That was six years ago. These days, she teaches four days a week, and has about 17 male students and 15 female students under her care, whom she teaches in separate classes.

Lessons are from 8.30am until 12.10pm, where the inmates get their lunch break, before class resumes again at 1.30pm, and ends at 3.20pm.

Emelda has since developed strategies to teach in “various styles and techniques” to suit her students. For example, she extends more help and guidance to her older students, as some inmates would have left school for more than 20 years.

Understanding that they’d need more time to get up to speed as compared to those who are younger, she extends the deadline for their homework, too. “I’d imagine it’s very scary for them … they tell me they haven’t touched a book (since then).”

As the authoritative figure in the classroom, she’s also learned to be “more sensitive” in her approach, including the tone of voice she uses with the younger inmates as well as those who are her peers, so as not to come across as “talking down” to them.

The circumstances of our inmates are different … Some of them come from very challenging backgrounds and have been through a lot.

“I’ll be objective-driven, and tell them what’s required for the exams, and they’re okay with that,” said Emelda.

At Prison School, inmates go through a fast-paced, compressed curriculum where a four- or five-year mainstream syllabus is squeezed into a period of about nine months. “So every year, you’re generating a new cohort of graduating students. I think this is the reason why I stayed on for six years – I don’t feel it’s been (that long),” she laughed.

I really want them to be employable, secure a good job and realise that there are more things to life than the vices they've been surrounded with.

Then, there’s also the limited range of teaching tools Emelda has at her disposal. “In mainstream schools, we have the luxury of IT, such as Powerpoint slides and videos – and we take these things for granted.”

But in the Prison School setting, resources would be “more more limited”. She has to be more selective in the materials she uses for her lessons. For instance, she isn’t allowed to show her students as many videos as she would like to, or print, say, an entire current affairs article for them.

“It’s quite challenging for the teachers to ensure that the students aren’t shortchanged – the inmates need to know these issues, but they don’t need to reach the extent of knowing too much.”

Despite the unique challenges of her job, Emelda told CNA Women she doesn’t think she could have stayed in the job for this long without support from the school’s management and her fellow teachers.

A HUMBLING EXPERIENCE: “LIFE IS NOT AS SIMPLE AS IT IS”

Working in Prison School has not only shaped her outlook in life, it has filled her with more gratitude for things people often take for granted, such as a job, a stable income and family support.

“It really humbles me as a teacher – as I said, the circumstances of our inmates are different … Some of them come from very challenging backgrounds and have been through a lot.

“It matures me, and makes me understand that life is not as simple and as straightforward as it is, and there’s no place for judgement.

“When I’m in class, I don’t bother to find out what the inmates are in for,” Emelda added. “They’ve been charged and are in prison to serve time. So my job is not to know what happened but to make sure their time spent is done meaningfully.”

Emelda said that she has been surprised by inmates asking her for homework – something she’d never encountered while teaching in a mainstream school. They would ask her, “Can we have more practice papers? Can we have more notes?”

It is because they are very concerned about their results, she said, especially those who are looking for a better job after they are released. “I really want them to be employable, secure a good job and realise that there are more things to life than the vices they've been surrounded with.”

IMPACTING THE LIVES OF INMATES

Through her job at Prison School, Emelda has learned to not underestimate the power of small acts of kindness, which could have a profound impact on the lives of the inmates.

Every time I step into the prison, I feel a sense of hope.

Emelda recalled a former female inmate who was gifted in writing. She was part of a writing programme in Prison School where inmates were required to write a story.

“During class, she came to me and asked to proofread and check what she’d written,” Emelda recounted. “I didn’t think much about it – inmates write a lot, so I was just checking her grammar and helping her to make it better.”

Little did she know that after her student was released from prison, her writing became part of a book titled Love Beyond The Walls, an anthology of 10 stories written by mothers who were previously incarcerated. The book was launched at The Istana.

Afterwards, the inmate told Emelda that she had met President Halimah Yacob at the book launch and had brought her family there. “I was really happy and proud of her, and I’m not surprised as she’s such a natural writer,” said Emelda.

“A random act of help that you assisted them with or word of support actually goes a long way for them.”

Another incident involved a middle-aged inmate who shared that her teenage daughter was taking the O-Level exams. The inmate was taking her O-Levels that year too, and told Emelda that Prison School had made her closer to her daughter.

“When her daughter visits her at the prison, she now has something in common to talk about, and her daughter has become inspired (by her mum’s effort in studying).”

While some inmates may not be academically very strong, said Emelda, she’s heartened when they tell her that they’re happy to learn, and are looking forward to taking the knowledge back to their children once they’re released from prison.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t take much for Emelda to feel content and fulfilled in her job. “As long as I don’t see the inmates coming back (to prison), I’m more than happy.

“Every time I step into the prison, I feel a sense of hope. I don’t feel down or depressed as the students are waiting for you to impart your knowledge – they are looking forward to the lessons, and they want to learn. That’s my personal motivation.”

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg (CNAWomen[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg).