This fast fashion designer shut down all her boutiques at a six-figure loss to start afresh – and sustainably

Angis Tiew shut down all her Little Match Girl fashion boutiques, emptied her company bank account, and went from producing 3,000 pieces to 30 per design. CNA Women finds out why motherhood inspired this Singaporean entrepreneur to give up decades of hard work and sizeable profits in this instalment of our women in sustainability series.

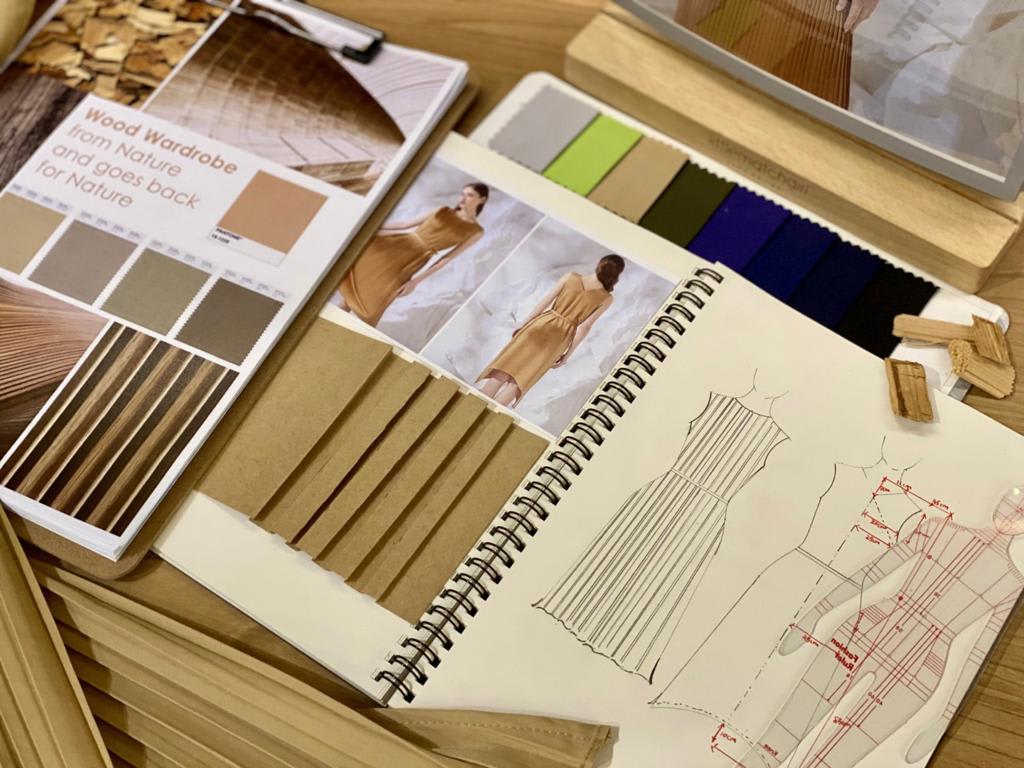

To reduce fabric waste and pollution, sustainable fashion entrepreneur closed her fast fashion boutiques at a huge loss to transit to slow, sustainable fashion. (Photo: Angis Tiew)

When most fast fashion brands address environmental pollution, it usually means merely introducing a sustainable line within their broader collection or switching to more sustainable packaging.

For Angis Tiew, there were no half measures. In 2018, the founder of Singapore label Little Match Girl shut down all six of her fast fashion boutiques which she had painstakingly built over 15 years.

This was no public relations stunt. It came at a huge price.

Tiew had long rental leases left at her boutiques. “My husband and I went from landlord to landlord to end our rental leases. Some required us to forfeit our three-month deposit. One required us to pay six months’ rental. We dried out our company bank account and lost a large six-figure sum,” said the 43-year-old.

Exiting the fast fashion race and ceasing production altogether for a year, Tiew and her husband Can Heng, 49, eventually launched a smaller scale green fashion brand. They kept the Little Match Girl branding but now used sustainable fabric in their designs.

It was much less profitable, however. The brand only makes 5 per cent of the profit it used to make at the peak of its fast fashion production. While she used to produce 3,000 pieces per design, Tiew has reduced production size by a hundredfold, producing small batches of 30 pieces per design.

HITTING PAUSE ON FAST FASHION

Tiew knows about fast fashion. It was how she grew Little Match Girl from a small shop at Far East Plaza to 12 boutiques between 2006 and 2008. At the peak of her business, she sold 15,000 pieces of clothing each month.

I never stopped to wonder if the fabrics were sustainable or biodegradable. I didn’t care. What I cared about was how much profit we made after selling clothes.

“Rental costs were high so we needed to sell as much as we could to cover rental. I had to come up with new designs all the time. In fast fashion, we usually use lower cost fabrics such as polyester and spandex, which tend to be at least three times cheaper than cotton. I never stopped to wonder if the fabrics were sustainable or biodegradable. I didn’t care. What I cared about was how much profit we made after selling clothes,” she confessed.

“Most of the time, I was busy opening new stores and recruiting staff, creating promotions and running sales. I repeated this every month and every year. It was a cycle and I was like a hamster in a wheel,” she reflected.

In 2009, she got married, and her husband joined her as a business partner. Two years later, they had a son together, and an unexpected change overcame her.

“When they put my baby in my arms, I teared to see how perfect he was. I realised all I wanted was for him to be healthy and happy. I decided to step back from my business operation to spend more time with him. I also began to go green, choosing organic food and bamboo clothing for my son,” she recalled.

Over time, she began to see the irony of choosing bamboo clothing for her son, while producing polyester and spandex clothing in large quantities for her business.

“One day, I read an article and realised how much the fashion industry contributed to pollution. While I was trying to be the best mother, I was creating an unhealthy Mother Earth for my son,” she said.

That’s what set Tiew on her sustainable journey. Over the next few years, she and her husband made a conscious effort to reduce their boutiques from 12 to six to break the fast fashion cycle. Finally, in 2018, they shut down all six remaining boutiques.

Watching the fashion business she built shut down, Tiew felt oddly at peace. “In the past, we had to keep producing and selling more clothes to cover rental, repeating the same process without a mental break. My husband and I felt relieved to be finally able to do what we wanted,” she said.

At first, the idea was to simply leave the fast fashion world. But when Tiew’s son asked the couple why they had stopped working, they became concerned about setting a bad example for him. “We did not want him to think that you don’t need to work hard in life,” she said. That’s when Tiew and Heng took a serious interest in sustainable fashion.

TURNING OVER A GREEN LEAF

In 2019, the couple visited factories in Guangzhou, China, that they used to work with. “We found out that there was a lot of fabric leftover from big labels. If not sold and used in an upcycled design, it would end up in landfills,” she said.

One of the factory owners even took the couple to a deadstock market in March that year. “It was so huge that you can’t cover it in a day. It is similar to Chatuchak Market (in Bangkok). Unlike regular fabric markets where you collect the fabric card and buy a sample fabric to design, for deadstock fabric, you need to come up with the design first before going to the market to shop for the fabric,” she said.

“Operators sell fabric by the kilogram, instead of by rolls as in regular markets. They won’t give you any fabric content. Based on experience from the texture and how it feels, you have to make a decision on the spot. Whatever you get one day, you won’t get another day, so it’s impossible to replenish designs,” she said.

Tiew brought 10 designs with her, and after an entire day fabric shopping, went home with 50 rolls of fabric. They visited the market again in June and September that year to replenish their fabric and began to sell small batch designs from upcycled deadstock fabric online.

“In the past, mass production was important because the more we sold, the more profits we could earn. But we ended up always doing sales to meet our sales target. This creates a lot of unwanted clothing for landfills.

“Now that we produce in small batches, we can test the market first. If a design is not doing well, we can improve our design for the next batch. We no longer need to do sales,” she said.

“It was hard to explain to the factory we had been working with in Guangdong that we wanted to manufacture 30 pieces per design instead of 3,000 pieces, because the effort to produce the clothes in small batches is the same, but the income is very different. However, we explained that we wanted to leave a less polluted environment for the next generation and the factory owners somehow accepted the idea,” said Tiew.

However, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the couple were unable to make their usual trip to China to restock deadstock fabric. “It felt like a good time for us to rethink our sustainability journey. We realised that ultimately, deadstock fabric is not biodegradable, and will not decompose in landfills,” she said.

The couple searched for alternative sustainable options and eventually decided to use Tencel, a fabric made from sustainably grown wood. Little Match Girl switched to Tencel at the end of 2020.

“We liked that the production process is environmentally responsible and that it comes from nature and can revert to nature. It is certified biodegradable and will decompose relatively quickly in landfills.

“Tencel also keeps us very cool and fresh in a hot and humid climate like Singapore. Many people think sustainable fashion is not comfortable or stylish, but that doesn’t have to be true” she said.

SUCCESS BEYOND NUMBERS

From a pure e-commerce model, Little Match Girl has since gone on to open two stores, one at Amoy Street in 2020 and another at Raffles City Shopping Centre in 2021.

“The problem with selling clothes online is that there are more returns because sometimes the size doesn’t fit as well, or consumers don’t like the colours when they see the actual item.

“These returns create more carbon footprint. By having a small shop, we are encouraging customers to try before buying. We also wanted customers to feel how gentle Tencel is on the skin and create more awareness for green and slow fashion,” Tiew said.

In that vein, Little Match Girl is also part of Raffles City Shopping Centre’s Project Green showcase at its Level 3 atrium space, which will run until Sep 25.

“In Singapore, there still aren’t many local green labels, so this project helps to create more awareness for local sustainable brands among shoppers. It also gives us the opportunity to share with customers about climate change and how we can make sustainable living part of our lives,” she said.

Despite the progress Little Match Girl has made in their sustainable evolution, lower production quantity has affected profitability. “We are not earning much now. When you come down to numbers, you won’t say we are successful. But when it comes to personal fulfilment, I think it has been successful,” she said.

“My husband and I have been discussing the true value in our lives. What we want to give our son is not material wealth, because that is superficial. We want to leave him wisdom and a mindset that can accompany him through his life after we’ve left. We also want to work harder for the environment, so that the next generation will be able to live better,” she said.

CNA Women is a section on CNA Lifestyle that seeks to inform, empower and inspire the modern woman. If you have women-related news, issues and ideas to share with us, email CNAWomen [at] mediacorp.com.sg (CNAWomen[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg).